NOTABLOG

MONTHLY ARCHIVES: 2002 - 2020

| MAY 2019 | JULY 2019 |

What a Jolly Good Time! Yanks Beat Boston in London!

For the first time in Major

League Baseball history, two storied American baseball franchises

faced off in a regular season MLB game in Europe. At London

Stadium, today, the New

York Yankees out-slugged the Boston

Red Sox, in a marathon 4+ hour game, with a score more befitting the National

Football League (and we're not talking "soccer"): 17-13.

Meghan Markle (a potential

distant relative of the Boston Red Sox outfielder Mookie Betts) and Prince

Harry were on hand, visiting both clubhouses, and the mound itself,

where they accompanied ten

participants of the Invictus Games, who threw out the ceremonial

first pitch. There was a really lovely performance by the Kingdom

Choir of the National

Anthems of both the United States of America and Great Britain [MLB

video link], and the seventh-inning stretch gave 60,000+ folks, across the pond,

a chance to sing "Take

Me Out to the Ballgame" [Goo Goo Dolls, YouTube link]. And because

this was considered a Boston "home game," we were even treated to a recording

of Neil

Diamond's "Sweet Caroline" in the middle of the eighth inning.

But in the end, the Yanks outlasted the Sawx, who played for the first time in

their 100-year old rivalry on artificial

turf; the teams scored a combined 30 runs (second highest combined

score in the history of their rivalry) and will meet again tomorrow (10 am

Eastern time) to close out their MLB debut on the London Sports Stage. The game

ended with Frank Sinatra singing, What else?: "New

York, New York" [YouTube link].

Song of the Day #1699

I introduced this song and essay on Facebook with the following preface:

Whatever your social, religious, philosophical, or cultural views, if you

embrace the basic principles embodied in this country's "Declaration of

Independence"---and its enunciation of the individual's rights to life, liberty,

and the pursuit of happiness---then it is time to take a "Stand" for Stonewall

on its Fiftieth Anniversary. Indeed, as the lyrics to today's song of

the day state: "Stand! You've been sitting much too long. There's a permanent

crease in your right and wrong." Check it out:

Song of the Day: Stand!,

words and music by Sly

Stone, was recorded by Sly

and the Family Stone in 1969. This was the title

song to the group's fourth

studio album and was the last song they played on their set list at Woodstock---this

year's first bona fide Woodstock

Golden Anniversary moment, the

theme of our 2019 Summer Music Festival. It was also a song that was

featured on the

jukebox of the Stonewall Inn, which

in the wee hours of this very day, fifty

years ago, was raided

for the umpteenth time by the New York City Police Department.

Perhaps the police didn't get the

payola they expected from the Mafia-owners of the bar, since bars

that served alcohol to people engaging in "disorderly conduct" (code for simply

being gay) would be denied

a liquor license in New York City. But this time, the patrons had had

enough; they were, indeed, 'mad

as hell and not going to take this anymore' [YouTube link]. They

pushed back, rioted, and fought for six days in a siege against political

oppression---giving birth to the modern

gay liberation movement.

For those who are uncomfortable

with this whole subject, as if it were some "leftist" expression of "identity

politics," we need to

make one thing perfectly clear (a phrase often attributed to

President Richard

Nixon, who took the White House fifty years ago this year): Both

"liberals" (going

all the way back to the policies of FDR) and "conservatives" (of both

the McCarthyite and religious

right variety) have played a part in crafting repressive laws in the

United States aimed at crushing homosexuality. It is neither our job nor our

responsibility to change the minds of those who find "alternative lifestyles"

repugnant or who believe that same-sex

relationships are a sign of "sickness" or "sin". Whatever one's

cultural, religious, philosophical, or political views, it all comes down to liberty.

If one values human liberty, one must recognize that state-sponsored terrorism

against individuals---simply because of who they love or how they

love---continues to this day across the world. Seventy countries still maintain

laws that make it illegal to engage in same-sex sexual activity, and so-called

"leftist" regimes have been among the most repressive, in this regard. Whether

in the name of politics or religion, these countries have used imprisonment,

flogging, and torture to punish those who are different, and in

ten countries, execution---by

stoning, hanging, beheading, or being thrown off buildings---is government

policy, legitimized by various states' interpretations of Islamic

law. The battle cry of Stonewall is as prescient today as it was

fifty years ago. Indeed, "eternal

vigilance is the price of liberty." And those who value liberty need

to embrace a future in which the Rainbow

Railroad [CBS News link] is no longer required to save those who are

being persecuted in other countries for their sexual orientation.

In the United States, there were heroes in the battle for individual rights prior

to Stonewall, who fought government entrapment and discrimination

against "the

love that dare not speak its name"---going all the way back to the

1920s, with the Society

for Human Rights and into the 1950s, with organizations such as the Daughters

of Bilitis, the Mattachine

Society, and, among individuals, the courageous Frank

Kameny, who challenged "The

Lavender Scare" [PBS video link].

But the significance

of the Stonewall Uprising by a group of individuals who were too

often marginalized and brutalized by the police, the courts, and the

culture-at-large is that, in its fundamental premises, it was based upon

a sacrosanct libertarian principle: that every human being, regardless of

age, ethnicity, gender, race, or sexual orientation, has a right to equal

protection under the law, a right to life, liberty, property, and the pursuit of

happiness, without infringement by the coercive, oppressive tools used by

municipal, state, and federal governmental institutions. This month, New York

City's Police

Commissioner James O'Neill apologized for the NYPD's actions fifty years ago at

the Stonewall. This was no mere nod to "political correctness." The

commissioner recognized that "[t]he actions taken by the NYPD were wrong, plain

and simple. The actions were discriminatory and oppressive and for that I

apologize." Even

the New York Yankees unveiled a plaque in Monument Park to commemorate this date

in history.

We can listen to the lyrics of today's song as an expression of the libertarian spirit

of the Stonewall

Rebellion: "Stand! There's a cross for you to bear. Things to go

through if you're going anywhere. Stand! For the things you know are right. It's

the truth that the truth makes them so uptight. Stand! You've been sitting

much too long. There's a permanent crease in your right and wrong. Stand! They

will try to make you crawl. And they know what you're saying makes sense and

all. Stand! Don't you know that you are free. Well at least in your mind if you

want to be. ... Stand! Stand! Stand!" I stand in solidarity with those brave men

and women who fought for their rights half-a-century ago on this day. Check out the

album version of this song and its

energetic performance by the group at Woodstock [YouTube link].

Postscript (29

June 2019) Justin

Raimondo, Outlaw, RIP. Justin lost his battle with lung cancer and

has died at the age of 67, on the eve of the fiftieth anniversary of the

Stonewall Rebellion. I knew JR from way back when---going all the way back to

when he wrote that monograph for Students

for a Libertarian Society, "In

Praise of Outlaws: Rebuilding Gay Liberation," which saw Stonewall

and the rise of the gay liberation movement as a distinctively libertarian

event. And he was right. A lightening rod for many people, antiwar.com was

his passion, and though we had our disagreements through the years, he was

always fighting against the policy of "perpetual war for perpetual peace."

Postscript #2 (30

June 2019): In another thread on Facebook, I had a bit of a discussion with

regard to whether the

struggle for "gay rights" is over in the United States, and I made

the same point in that thread that I make here in my Notablog post: Seventy

countries across the world still treat same-sex activities as a crime punishable

by imprisonment, flogging, and torture, and ten of those countries treat it as a

crime punishable by execution (beheading, hanging, and being thrown off

buildings).

It was suggested that I might be implicitly advocating trying to intervene in

those other countries to change their domestic policies; as a firm

non-interventionist in foreign policy, I am totally against such intervention

even for the purpose of human rights abuses abroad. But that does not mean that

I favor the long history of foreign aid policies practiced by the United States,

which involves expropriating the American taxpayer for the purpose of sending

"foreign aid" to despotic regimes abroad, like Saudi Arabia, which are then

required to use that "foreign aid" to purchase US munitions, which they can use

in their wholesale slaughter of people in Yemen and elsewhere. US relationships

with such despotic regimes is legion, and our current President believes "it is

good for the economy."

Considering that the Saudis gave us 17 of the 19 hijackers who flew planes into

the Twin Towers and elsewhere and that they were probably complicit in the 9/11

attack, I would say that what might be "good for the economy" is most definitely

not good for the stability of the Middle East and other hot-spots around the

globe, where the US has a record that even Trump himself once said was not so

"innocent."

No, we cannot change the domestic policies of foreign governments that engage in

violations of human rights. But that doesn't mean the U.S. taxpayer should be

subsidizing them. This is not a battle for "gay rights"; it is a battle for

individual rights, and individual rights don't cease at the borders of the

United States.

But yes, Stonewall 50 is a a cause for celebration for all those who believe

that individual rights apply to every person regardless of sexual orientation.

And I stand in solidarity will all those who sacrificed their lives over the

past century to get this country to recognize those rights.

Postscript #3 (1

July 2019): I added this comment to a Facebook post by Tom

Palmer, who provided a link to a fine 2016 article by David Boaz, "Capitalism,

Not Socialism, Led to Gay Rights:

Good piece by David Boaz and thanks for posting, Tom!

I've heard from quite a few of my very orthodox Marxist colleagues over the

years who believe that homosexuality is one of the decadent offshoots of

capitalism (guess they missed all that stuff that went on in the ancient world)

and that it would wither away, like the state, under full communism.

They also leave out the part that gulags will play in helping the withering-away

process.

Of course, orthodox Marxists actually reject the whole development of 'identity

politics' (which the fight for same-sex individual rights is most certainly not)

as a way of obfuscating the "essential" conflict between proletarians and

capitalists.

I've argued this past weekend that the Stonewall Rebellion was in its essence a

libertarian expression of the fight for the individual's right to live his or

her own life, socialize in privately-owned establishments without police

harassment, and pursue happiness without the interference of state-sanctioned

terrorism. That fight goes on globally and even within this country; the battle

for "gay rights" is not over, as James Kirchick says in "The

Atlantic." If it is over, I invite anyone to go into the reddest of

red states (or any sections in "blue" states in which "tolerance" is not a key

cultural value), holding hands with their partner, and in open spaces, sharing a

romantic kiss as the sun sets. Then we'll take a poll and see how many folks get

their heads bashed in.

On all these issues of markets having changed traditional notions of the family,

women, and sexuality, over time, I highly recommend the work of Steve Horwitz,

especially his book Hayek's Modern Family: Classical Liberalism and the

Evolution of Social Institutions and, of course, his essay in The

Dialectics of Liberty: "The Dialectic of Culture and Markets in Expanding

Family Freedom." Check out the abstract here.

I agree that the essential political and legal battles have been won, but

changing political culture and mores is a long-term process, and often leads to

a kind of political/legal backlash against which one must always be vigilant.

And as a noninterventionist in foreign affairs, while I would never advocate

interfering in the domestic affairs of other countries, the fact remains that

seventy countries still categorize homosexuality as a crime punishable by

imprisonment, flogging, and torture, and in ten of those countries, it is

punishable by execution (beheading, hanging, or being thrown off buildings). No,

the US has no business being the world's policeman on violations of human

rights, but the least it could do is to stop expropriating its taxpayers into

providing "foreign military aid" (a fancy phrase to describe providing U.S.

financial assistance to foreign governments that are then obligated to purchase

U.S.-manufactured munitions) to reactionary governments, such as Saudi Arabia,

which has a horrendous human rights record, and is using all those munitions to

slaughter people in Yemen.

Ah, but our President says it's "good for the economy."

Posted by chris at 12:01 AM | Permalink |

Posted to Culture | Dialectics | Music | Politics

(Theory, History, Now) | Religion | Remembrance | Sexuality

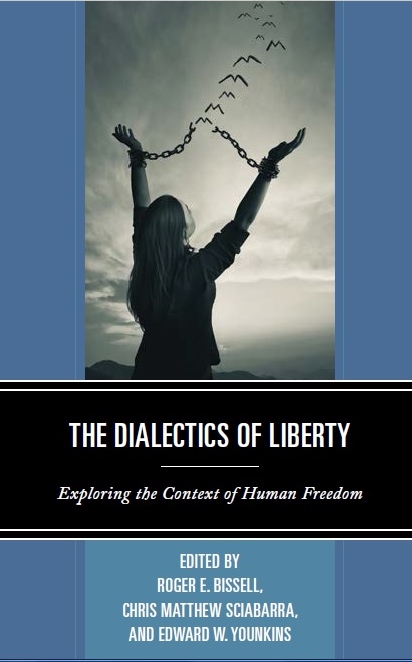

The Dialectics of Liberty: Some Nontrivial Thoughts About Its Meaning

I've written on quite a few threads throughout Facebook, and am collecting on

Notablog, as I go along, all the random (though not unrelated) points I've made

in response to those who question (again) the very meaning of "dialectical

method", which is the basis of the new anthology, coedited by Ed Younkins and

Roger Bissell: The

Dialectics of Liberty: Exploring the Context of Human Freedom.

Check this link periodically, if you're not following the multiple threads on

which I've commented, with regard to this work:

o In my use of the term "dialectics", it is a prism through which to understand

social problems. It is the "art of context-keeping", which asks the social

theorist to grasp the larger systemic and historical context within which social

problems arise. No social problem is to be looked at as if it were an atomistic,

isolated unit, separable from the context in which it is embedded. So in

"exploring the context of human freedom" (our subtitle), we're asking

libertarians to show a profound regard for that larger context, which includes

personal, cultural, and structural (political-economic) elements especially if

their aim is to change society. It's not simply: Get rid of (or minimize) the

state and everything will be fine. There are other, deeper issues that must be

addressed in understanding social problems and attempting to resolve them. This

way of looking at the world may have been taken up by the left, but it

originated with Aristotle, who wrote the first treatise on dialectical method

("Topics"), even though his discussion of viewing issues from multiple "points

of view" is peppered throughout the entire Aristotelian canon. Hegel himself

called Aristotle "the fountainhead" of this dialectical method. I'm not going to

deny that I learned much about dialectical method from a very high profile

Marxist scholar, my mentor Bertell Ollman---and it was through him that I

learned to use the method as one of social analysis. My "Dialectics and Liberty

Trilogy" (which consists of Marx, Hayek, and Utopia, Ayn Rand: The

Russian Radical, and Total Freedom: Toward a Dialectical Libertarianism)

was geared toward taking back the method for use by libertarians to bolster

their approach to the study of freedom---and of the forces that constrain it.

o Even logic can be abused if it is based on false premises; some philosophers

have deduced whole systems of philosophy from a single faulty premise.

Dialectics is the handmaiden of logic, and can be undermined by false premises,

faulty induction, incorrect identification or interpretation of historical

facts, etc. And each "art" can be used as a rationalization for any kind of

lunacy. All the more reason to fight against its ties to lunacy. One of the

guiding purposes throughout my entire intellectual life has been to take back

dialectical method and to build a paradigm by which to strengthen libertarian

thinking, which itself can succumb to nondialectical, utopian lapses. And if

implemented would lead to dystopian consequences.

o The Soviets---and the Nazis---were masters of distortion and propaganda; it

was one of the elements that they used to defend their authority and maintain

their power over their own populations. Whether it was the claims to being based

on "scientific socialism" in the case of the Stalinists or of admiring the

eugenics work of U.S. scientists in the case of Hitler and his genocidal

tyranny, each regime had a propaganda machine that allegedly used "science" as

the basis for their claims to power. The irony is that not even Marx would have

approved of the "Soviet" application of "scientific socialism"---given that he

believed genuine socialism could only emerge out of a very advanced stage of

capitalism that had basically solved the problem of scarcity (to the point where

the society could afford to give 'from each according to his ability to each

according to his needs'). Of course, as I argue in two of the books of my

trilogy, scarcity is never resolved (because, at the very least, we are all

mortal and time for each agent is inherently scarce), and Marx's predictions of

a post-scarcity society were a product of what Hayek called a "synoptic

delusion." Not a very "dialectical" insight on the part of Marx; where he was so

good at criticizing the "utopian socialists" for their contextless proposals,

he, himself, succumbs to the very utopian pitfalls he criticized.

o I think that even if Marxists are not into post-scarcity as a goal, they can't

have their cake and eat it too: they can't endorse the maxim "from each

according to his ability to each according to his needs" if there is not enough

ability---and not enough goods and services to go around. That's why Marx

predicated the achievement of communism as an outgrowth of a very advanced stage

of capitalism, which, in his view, would have essentially solved the problem of

scarcity. If everything is abundant, no need to worry about expropriation, and

the state will wither away. If you believe that, I have a nice bridge in

Brooklyn I could sell you.

o I think that in the case of conservatism, for example, there is a very real

understanding of what conservatives believe is essential to the sustenance of a

free society. For them, it is typically tradition and the slow evolution of

mores over time (at least in the Burkean and Hayekian sense) that serves as the

context upon which a stable free society can be built. My disagreement with the

approach of many conservatives on this issue is that though they understand the

need for a larger cultural context that is supportive of free institutions, they

don't recognize how free markets themselves often undermine traditions and

challenge traditional mores. As I may have mentioned, Steve Horwitz's article on

the family, in The Dialectics of Liberty (and in his own book on Hayek

and the family) makes this case quite well. As for "dialectical objectivism"---I

can think of one

book in particular that reconstructs Rand's philosophy through that

prism of interpretation, but the title escapes me at the moment. :)

o A postscript to my above comment, something I shared with my friend Ed

Younkins: While it is true that we can use "dialectical" as an adjective to

modify any "ism", it is also true that just about anybody can be "dialectical"

and "logical", for as Aristotle said, dialectical thinking is like the

"proverbial door, which no one can fail to hit" (or even a broken clock can be

right twice a day). The point however is that we aim for it to be anchored to

the facts of reality, which is why, even at their best, when conservatives try

to be dialectical, they are missing something in their contextual

arguments--namely, that the market itself challenges the very mores they claim

to be the only basis upon which a stable market society can be built. Every

person and virtually every school of thought can exhibit dialectical and logical

thinking -- since these are constituents of thinking as such. That doesn't make

them fully dialectical (or fully logical) by a long shot; hence--the need for a

"dialectics of liberty." But even in our book... we don't settle on one vision

of what that means. I would like to think that we're getting closer than anybody

else toward hammering out a more context-sensitive, fact-based model for

thinking more clearly about liberty and the context it requires for its

sustenance.

o I agree that the Marxist appropriation did much to destroy what was a

supremely important methodological approach. All the more reason to resurrect it

with a throwback to its realist Aristotelian beginnings. The Marxists didn't own

dialectical method, and in many ways, destroyed the enterprise altogether by

falling into the pitfalls of nondialectical, utopian thinking. We hope not to

make the same mistake---and suffer the same dystopian consequences.

In response to those who think that "dialectical method" is a fancy phrase for a

"trivial" mental process, I state:

o The point, however, is that as "trivial" as it sounds, there are not many

folks who can think in a consistently logical or dialectical manner---look at

the entire field of U.S. politicians for a lesson on how disintegrated their

views are, and the effects that such views can have on the world at large.

Indeed, right here in New York City, capital of the world, the DeBlasio

administration is engaging in a

systematic attack against education for the gifted and talented,

those few schools that actually do teach children in a more enriched and

systematic way.

o Ayn Rand herself talked about how modern education often put children on an

unequal cognitive footing because pedagogical methods tended toward

dis-integration and rote memorization, while also teaching a whole generation of

kids about the nature of obedience to authority. That which seems "trivial" is,

in fact, not trivial at all. Training children in the principles of efficient

thinking, providing them the tools by which to think through an argument,

follow it to its logical conclusions, understand its potential unintended

consequences, and trace the interconnections between topics and problems within

a larger system across time (in which those topics and problems often become

preconditions and effects of one another) is a highly sophisticated art. It's

not something that is typical of American education, whether in the early grades

or in college. In fact, as "specialization" has proceeded, and as studies have

become more and more compartmentalized, integrated, interdisciplinary work is

put at a disadvantage. One of the best things about The Dialectics of Liberty and

the series of which it is apart, edited by Ed Younkins ("Capitalist

Thought: Studies in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics") is its

emphasis on the interconnectedness of the humanities and the social sciences.

I'm delighted that our new book is part of that series, thanks to Ed and his

monumental efforts. [And check out one of Ed's new entries in the series, Perspectives

on Ayn Rand's Contributions to Economic and Business Thought]

I'll add to this entry, if and when I say anything more on this subject. Of

course, it would really be nice if folks read the new collection before

commenting on its themes, but I've been through this before and have been

blessed with the patience of a saint---even if what I say sometimes does not

sound too saintly. :)

Posted by chris at 09:34 AM | Permalink |

Posted to Culture | Dialectics | Education | Elections | Politics

(Theory, History, Now) | Rand

Studies

Pope Francis and the Caring Society: A Review

A couple of years ago, I received Pope

Francis and the Caring Society (Oakland, CA: Independent

Institute, 2017) from David

J. Theroux of the Independent

Institute. I very rarely review books for Notablog, but this sure did

look like an interesting work. And it is, in fact, a challenging volume worthy

of attention.

Consisting of seven chapters written by a diverse group of authors, it is edited

by Robert

M. Whaples and includes a foreword by Michael

Novak. The book engages in a dialogue of sorts with Pope

Francis specifically on matters of political economy and social

justice. Novak states upfront that "the book shares [the Pope's] commitment to

Judeo-Christian teachings and institutions. In the process, the book's authors

are seeking constructively to engage and educate civic and business leaders and

the general public to understand the legacy and meaning of the natural law,

moral and economic principles of liberty, personal responsibility, enterprise,

civic virtue, family and community, and the rule of law" (xix).

But editor Whaples makes it clear in his Introduction that this book is designed

"to advance the dialogue at a critical juncture" in Pope Francis's papal reign

(2). It seeks to educate the papacy on the virtues of free markets in resolving

many of the problems that the Pope has blamed on "capitalism"---whatever that

term means. Indeed, referring to Pope John Paul II, Novak suggests that

"capitalism" means different things to different folks: for some, it is about

the liberating force of free trade and open markets; for others, it is about

special privileges vested in the wealthy by a state that bolsters their power at

the expense of the poor (xxv). And nothing could be more un-Christian than

embracing a system that is designed to exploit the least-advantaged people in a

society.

One of the most important contributions of this book is that it places Pope

Francis's views of capitalism in an understandable context. This is a man who

came from Argentina---with its history of Peronist corporatism, which enriched

its business clients. And if this is what Pope Francis views as "a model of

capitalism," one "that friends of free markets rightly reject as capitalism at

its worst," not reflective of how markets work under different institutional and

cultural contexts (3), then it certainly helps to explain the Pope's "much lower

opinion of capitalism and market economies than most economists" (25). This is a

crucially important point in any exploration of the Pope's economic perspective.

As one who has embraced dialectical

method, the supreme "art of context-keeping," I have grown wary of

using the very term "capitalism"---despite Ayn Rand's own projection of the

"unknown ideal" that such a social system would embody. Her concept of

"capitalism" is almost a Weberian "ideal type," organically connected to the

notion of individual rights, in which all property is privately owned. But even

she argues that such a system has never existed in its purest form. In many

ways, her ahistorical re-conceptualization of terms such as "capitalism" and

even "government" (ideally viewed as a voluntarily funded institution strictly

limited to the protection of individual rights)---differs fundamentally from "the

known reality."

Indeed, as Friedrich

Hayek reminds us in "History and Politics," his introductory essay

to Capitalism

and the Historians: "In many ways it is misleading to speak of

'capitalism' as though this had been a new and altogether different system which

suddenly came into being toward the end of the eighteenth century; we use this

term here because it is the most familiar name, but only with great reluctance,

since with its modern connotations it is itself largely a creation of that

socialist interpretation of economic history with which we are concerned"

(14-15, 1954 edition, University of Chicago Press).

Given this reality, I found Andrew

M. Yuengert's chapter, "Pope Francis, His Predecessors, and the

Market," to be especially important. Yuengert argues that, as a "citizen of

Argentina---a country that is without political institutions capable of putting

the economy at the service of the common good and that instead uses and is used

by business and political interests to increase the power of business and

political elites," the Pope witnessed "a prime example of how crony capitalism

and statist control of the economy can wreck a country that deserves better"

(43-44). Nevertheless, it is also true that the Pope's analysis of the market

economy has been in keeping with an emerging tradition of "Catholic social

teaching" that is increasingly at odds with the very idea of a market society

(47).

Samuel Gregg,

in his chapter, "Understanding Pope Francis: Argentina, Economic Failure, and

the Teologia del Pueblo," reinforces Yuengert's points. He argues

correctly that the Pope's views of the market economy "did not emerge in a

vacuum" (51). Likewise, Gabriel

X. Martinez focuses on the oligarchic nature of Argentinian economic

nationalism, pointing out that even attempts to "liberalize" the economy have

benefited entrenched interests. All of this is the prism through which the Pope

views market societies; is it any wonder that he is at odds with those who offer

market solutions to government-created problems? Instead, he has adopted a

state-centered approach of massive government redistribution as the means to

alleviate poverty.

Lawrence J. McQuillan and Hayeon

Carol Park take on this issue with vigor. The authors point out the

obvious: A market economy generates the wealth that makes possible charitable

giving on a scale hitherto unknown. Government "redistribution" does not

generate wealth; it can only "coercively" take money from one group and give it

to another (89). They argue that "[f]orced government transfers actually destroy

genuine charity within society. They serve primarily to make people more

accepting of the use of force to achieve ends they consider worthy and produce

resentment and division among those forced to give to 'charitable' endeavors

they do not choose to support. Freedom of choice and the exercise of conscience

are better suited to making people more compassionate citizens" (90)---something

that should resonate with the Church's teachings. The authors also analyze Pope

Francis's early writings (under his given name, Jorge Bergoglio, archbishop of

Buenos Aires), in which he focused on "the limits of capitalism"---which

accepted many of the premises of the Marxist-hued liberation theology that

bloomed in Latin America in the 1960s and 1970s (92). The authors make fine use

of the Hayekian argument on "the knowledge problem" that permeates nonmarket

societies, and why governmental intervention is not the best way to achieve the

equality that the Pope seeks.

My favorite quote in this chapter comes from none other than President Franklin

Delano Roosevelt, who gave us the corporatist New Deal as an answer

to the government-induced 1929 Stock Market Crash and the Great Depression of

the 1930s that followed. FDR saw the dangers of fostering a "culture of

dependency" in the welfare state he himself was building: "Continued dependence

upon relief induces a spiritual and moral disintegration fundamentally

destructive to the national fiber. To dole out relief in this way is to

administer a narcotic, a subtle destroyer of the human spirit" (109). For the

same reason, these authors argue, Papal support for increased governmental

redistributive efforts will only undermine the ability of entrepreneurs to

produce the wealth that can support private charity. They warn that "[t]he road

to hell and to poverty is paved with good intentions" (111).

While this book does not address this Pope's views on non-economic topics (e.g.,

on the sexual abuse scandals of the Catholic Church or any evolution in Church

teachings on birth control and sexuality), it does focus some additional

attention on the environment, conservation, and the family, in chapters written

by A. M. C.

Waterman, Philip

Booth, and Allan

C. Carlson. Booth is especially good on the "tragedy of the commons"

(164) in generating environmental decay and industrial pollution.

Robert P. Murphy provides

a bold conclusion to the volume: "Historically, there has been an undeniable

tension, if not outright conflict, between religion and economics" (199). He

laments the "impasse" (199) and hopes that the current work can contribute to "a

foundation of mutual respect" as each side engages the other (201).

All I can say is: From Murphy's lips to God's ears.

Posted by chris at 04:15 PM | Permalink |

Posted to Austrian

Economics | Culture | Dialectics | Fiscal

Policy | Politics

(Theory, History, Now) | Rand

Studies | Religion | Sexuality

Song of the Day #1698

Song of the Day: Who

Is It? features the words

and music of Michael

Jackson, from the 1991 album, "Dangerous."

On this day, ten

years ago, the artist tragically died. As I note in today's Notablog essay,

"Michael

Jackson Ten Years After: Man or Monster in the Mirror," there are

still reasons to celebrate the art of somebody, even if it should be discovered

that they may have done something in their lives that was terribly destructive.

This particular track went to #1

on Billboard's Hot Dance Club chart. Its various versions

provide different hues of interpretation; check out the original

David Fincher-directed music video and his

beat box interpretation of the song in an interview with Oprah Winfrey,

which became the

basis of one of the song's remixes, and then hit the dance floor with

the slammin' Brothers

in Rhythm House Mix, the Brothers

Cool Dub, Moby's

Tribal Mix and Moby's

Lakeside Dub [YouTube links]. RIP, MJ.

Posted by chris at 12:05 AM | Permalink |

Posted to Music | Remembrance

Michael Jackson - Ten Years After: Man or Monster in the Mirror?

This essay makes its Notablog debut on the tenth anniversary of the tragic death

of Michael Jackson. It can also be found in the essay section of my home page here.

It deals with one of the most difficult issues we face in evaluating art---and

its creator.

Can Bad People Create Good Art?

Writing in The

New York Times, Charles McGrath asks: "Can bad people create good

art? If that question pops up on an exam or at a dinner party, you might want to

be wary. The obvious answer---so obvious that it practically goes without

saying, and ought to make the examinee suspicious---is that bad people, or at

least people who think and behave in ways most of us find abhorrent, make good

art all the time." McGrath then gives us a laundry list of folks who are

frequently cited as pretty bad people who created good art, among them such

notorious anti-Semites as the proto-fascist Ezra

Pound, composer Richard

Wagner, who "once wrote that Jews were by definition incapable of

art," and Edgar

Degas, whose anti-Semitism led him to defend "the French court that

falsely convicted Alfred

Dreyfus." (And Lord forbid any of you should respond with a slight

nod of aesthetic approval to just one of

these paintings, for it will only prove that you are a secret admirer

of young Adolf!)

But the list of "bad artists" who may have created "good art" is legion:

There's Norman

Mailer who "in a rage once tried to kill one of his wives"; the

"painter Caravaggio and

the poet and playwright Ben

Jonson [who] both killed men in duels or brawls"; Jean

Genet, gay prostitute and petty thief; Arthur

Rimbaud, who flaunted all the conventions of his time; Gustave

Flaubert, who "paid for sex with boys," and so it goes.

We can add to that list: Director Roman

Polanski, who fled the United States after pleading guilty to a

statutory rape charge, but who gave us the classic horror flick, "Rosemary's

Baby,"; the great neo-noir mystery "Chinatown,"

and "The

Pianist," a harrowing biopic of Holocaust survivor Waldyslaw

Szpilman (played by Oscar-winning Best Actor Adrien

Brody). Most recently, let's not forget: Producer Harvey

Weinstein, who may not have been an artist, but who produced Oscar

Award-winning films and Tony Award-winning plays, and was expelled from the Academy

of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences for a series of horrific

allegations leading to his arrest on charges of rape and sexual

assault---practically giving birth to the #MeToo

Movement; R&B singing sensation R.

Kelly, who was once indicted (and found not guilty) on charges of

child pornography, only to be re-indicted this past Februrary on ten counts of

aggravated criminal sexual abuse; funk musician Rick

James, who gave it to us with "Super

Freak," only to end up in prison on everything from draft evasion to

rampant drug use that led to kidnapping and sexual assault convictions;

long-beloved comedian Bill

Cosby, who is now serving a three-to-ten year sentence for aggravated

indecent assault.

In the ideological sphere, honorable mention goes to Dalton

Trumbo, among the blacklisted Hollywood

Ten, whose trials and tribulations were the subject of a

fine 2015 film starring Bryan

Cranston, which doesn't once mention that Trumbo

was an apologist for the Stalinist purges of the 1930s. But it does

remind us of what a gifted writer he could be, when you see re-created scenes

from the momentous 1960 epic "Spartacus."

And let's not forget Kate

Smith, whose recording of "God Bless America" has now forever been

banned from Yankee Stadium during the seventh-inning stretch, because she

recorded a couple of records almost ninety years ago (in 1931) with racist

lyrics.

Indeed, once we open up that ideological and historical can of worms, we're

faced with calls to obliterate various monuments to the American revolutionaries

who fought for life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, including Thomas

Jefferson, who, despite penning the Declaration of Independence and

speaking out against slavery, owned over 600 slaves himself, freeing only seven

in his lifetime.

Human beings are a complicated lot. As McGrath points out, however, it is very

misleading to ascribe "badness" and "goodness" especially in the context of

artists and art, because these concepts can have different referents: they can

point either to the person's moral worth or to the aesthetic merit of that

person's work. Take Wagner. For this film score fan, the

impact of Wagner on the art of the score is immeasurable. Even "[t]he

conductor Daniel Barenboim, a Jew, is a champion of Wagner's music, for example,

and has made a point of playing it in Israel, where it is hardly welcome. His

defense is that while Wagner may have been reprehensible, his music is not.

Barenboim likes to say that Wagner did not compose a single note that is

anti-Semitic." McGrath states further that "the disconnect between art and

morality goes further than that: not only can a 'bad' person write a good novel

or paint a good picture, but a good picture or a good novel can depict a very

bad thing. Think of Picasso's

Guernica or Nabokov's Lolita,

an exceptionally good novel about the sexual abuse of a minor, described in a

way that makes the protagonist seem almost sympathetic."

McGrath recognizes that art, like ideas, is one of those realms of human

experience that can inspire us, enlarging "our understanding and our

sympathies." He hits upon an even more interesting point when he states, in

almost Randian fashion, that "the creation of truly great art requires a degree

of concentration, commitment, dedication, and preoccupation---of selfishness, in

a word---that sets that artist apart and makes him not an outlaw, exactly, but a

law unto himself." Of course, from a Randian standpoint, there is a virtue of

selfishness, even if it is typically viewed as a vice. And it needn't mean that

the artist qua selfish is necessarily tortured or bad. Yet, it is

nevertheless true that many artists have been tortured souls throughout the

centuries. Finding ways to express their inner conflicts and tensions through

the sheer act of creation can provide for a kind of cathartic experience. For

those of us who respond to that art, it provides a form of objectification that

allows us to appreciate the art work on its own terms, whatever the moral merits

of the person who created it.

But comedian

Pete Davidson scored a few points in the Gallows Humor Department in

one of those "Weekend Update" segments on "Saturday

Night Live" [YouTube link]. "Once we start doing our research," he

quipped, "we're not gonna have much left, you know, because it seems like all

really talented people are sick." Well, I wouldn't go that far. Moreover, not

every artist has a cesspool for a soul. Thank goodness.

But when we admire a piece of art, whether it be a painting hanging on the wall

of a museum or a work of music, we don't have to contemplate how lost, how

tortured, or how awful the artist may have been as a person when they engaged in

the act of creation. If the work speaks to us, whether we respond to it on the

level of "sense of life" or just because of our mood on that particular day,

what we are responding to is that work, not necessarily to the person who

created it.

Distinguishing Between the Creator and the Creation

If we focus long enough on the artist, rather than the art, or the writer,

rather than what is written, we might be led to airbrush out of existence some

of the most important and influential artists or intellectuals---be they "good"

or "bad"---throughout human history. This is a subject that hits close to home

for a scholar such as myself. In my work, I have spent much time analyzing the

legacies of many individuals whose ideas stand in diametric opposition to one

another. Though I stand by the dialectical mantra that "context matters"--that

is, though I am inclined to place the work of a thinker within the larger

context of that thinker's life and the culture within which that thinker came to

maturity, all of which helps us to better understand his or her ideas---it would

never lead me to dismiss that thinker's work on the basis of their personal or

cultural context. Let's take Karl Marx as an example; many have focused on

evidence that he "lived

in filth and neglected his own children." That may be true. But I

would not treat his work with a sweeping ad hominem dismissal---especially

since one of my goals has been to grapple with his intellectual legacy and his

use of a dialectical method of social analysis, so important to my

own project of rescuing dialectics for libertarian theory. And, as a

Rand scholar, I have had to face all sorts of criticisms of Rand the person---from

those who despise her work, and who dismiss it wholesale on the basis of her

questionable personal attitudes toward everything from Beethoven to homosexuality,

or who view her as nothing more than a pop-novelist and cult-leader who had a

scandalous sexual affair with her protege, Nathaniel

Branden, twenty-five years her junior, which destroyed their personal

and professional relationship, and which she never acknowledged publicly. And on

the other side of that equation, I've had to come to grips with those Rand

acolytes who dismiss all of Branden's

work on the importance of self-esteem to human survival, because he

lied repeatedly to Rand as that relationship dissolved, thus showing him, and,

by extension, his ideas, as, at best, hypocritical, or at worst, a sign that he

was nothing other than a self-aggrandizing con man.

Michael Jackson and "Leaving Neverland"

And so, finally, we come to the subject of Michael

Jackson, the boy who became a man before his time, as he led his

brothers in the Jackson

Five straight into the Rock

and Roll Hall of Fame, and who, as a solo artist, amassed a

discography that has sold hundreds

of millions of records worldwide, giving him his own place in that

same famed

hall. Jackson's

impact on music, dance, fashion, and culture has influenced

scores of artists over the past fifty years. His music has been sampled, reinterpreted,

and resurrected by

everyone from Justin

Timberlake and Drake to Alien

Ant Farm, Chris

Cornell, and the 2Cellos [YouTube

links].

But there were those allegations that first emerged in 1993, when police

descended on his Neverland Ranch, investigating claims that Jackson had molested

a 13-year old boy. An exhaustive search found no incriminating evidence, though

a civil

case brought by the boy in question, Jordan Chandler, and his

parents, was eventually settled out of court. Later, in 2005, Jackson was

charged with the

child molestation of Gavin Arvizo, serving alcohol to a minor,

conspiracy, and kidnapping, facing twenty years in prison. His homes were

ransacked by the LAPD, but nothing incriminating was found, and an in-depth

investigation by the

FBI came up with no evidence of wrongdoing. In the end, Jackson was

acquitted of all charges.

As Forbes magazine

reported, however, choreographer Wade

Robson had testified

in the 2005 trial under oath, that as a child and young adolescent,

in the many years that he knew Michael Jackson, the artist had never touched him

inappropriately or sexually abused him. James

Safechuck, who spent time with Jackson in the 1980s, also defended

Jackson back in the 1993 case. Various events thereafter occurred which led

these two men to eventually file suits against the Jackson Estate, nearly four

years after Jackson's tragic death on June

25, 2009 (a decade ago this very day), seeking $1.5 billion in

damages, claiming that they had, in fact, been sexually abused by Jackson:

Robson, when he was between 7 and 14 years of age; Safechuck, when he was 10 to

12 years of age. Both the Robson and Safechuck cases

were dismissed

in probate court.

On January 25, 2019, at the Sundance

Film Festival, the documentary, "Leaving

Neverland," directed by Dan Reed, featuring both Robson and

Safechuck, as well as some of their relatives, made its debut. HBO showed the four-hour

documentary over two nights in March 2019, followed by an Oprah

Winfrey-hosted special, with Reed, Robson, and Safechuck as guests. I

watched the documentary in full and the "After Neverland" Winfrey interviews,

and was left feeling deeply saddened and sick at heart. The

dead cannot defend themselves, and the

documentary offered no cross-examination, no

counter-testimony [YouTube links], and no

alternative narratives [Quora Digest link]. But that didn't take away

the sting of hearing the shattering testaments or of observing the body language

of the two men as they painted shockingly graphic portraits of their sexual

abuse by someone who had befriended them, groomed them, and subsequently

betrayed their trust.

If none of what they say is true, it is a travesty to the memory of a man, who

was probably abused

as a child himself, and who went on to raise millions of dollars in

humanitarian aid for children worldwide with his "We

Are the World" single (co-written with Lionel

Richie) and his Heal

the World Foundation.

If only 10% of what they say is true, it is a horrifying portrait indeed. But

for the sake of this essay, which marks the

tenth anniversary of the tragic death of a truly unique artist, let's

say it's all true.

What does this mean for those of us who grew up listening and dancing to Michael

Jackson's music?

Reassessing Jackson's Artistry? Reassessing Myself?

Michael Jackson's music was, for all intents and purposes, like the

coming-of-age soundtrack of my youth.

Indeed, I can tell you that as a 9-year old kid, in December of 1969, I sat in

front of my black and white television and was inspired to see somebody about my

own age stepping out onto the stage of the "Ed Sullivan Show" to belt out "I

Want You Back" [YouTube link] like he was an old pro. I can't count

the number of times, as a mobile DJ in my college years, how I lit up the dance

floor with the propulsive beats of the Jacksons' "Shake

Your Body (Down to the Ground)" or "Walk

Right Now" [YouTube links] or how I got a group of tired teachers up

at a school reunion to dance over and over again to "The

Way You Make Me Feel" [YouTube link]. Or how MJ drew me into a world

of romantic intrigue with his

"Heartbreak Hotel" (aka "This Place Hotel") [YouTube link]. Or, more

personally, how I danced, with a blind date, to the disco beats of "Don't

Stop 'til You Get Enough" and "Rock

with You" [YouTube link] from MJ's pathbreaking solo album, "Off

The Wall." Or how awestruck I was when I saw him on the "Motown

25" special doing his sensational signature Moonwalk to

"Billie

Jean" [YouTube link] (predictably, on the recent "Motown

60" special, he was practically airbrushed out of existence). Or the

first time I saw the

chilling, thrilling video to the title track of the album [YouTube

link] from which "Billie Jean" emerged, the all-time global best-selling "Thriller."

Or that first sensuous kiss I experienced with somebody, in a moment of

intimacy, listening to the "Quiet

Storm" sounds of "The

Lady in My Life" [YouTube link] from that same album.

I saw MJ perform live in concert two times, once with his brothers (on the "Victory

Tour") and once as a solo artist (on the "Bad"

tour). He was a lion on stage, the quintessential song-and-dance man of his

generation who merged the grace of Astaire and Kelly with

the grit of the street. Filled with irrepressible energy that fueled more than

two hours of one greatest hit after another, his choreography was staggering to

watch, his vocals were purer than anything you'd hear even on a carefully

produced studio album. Even my mother went to those shows, she loved him

so much!

So, where does this leave me? Am I to feel guilty that my foot still starts to

tap, almost involuntarily, every time I hear that bass line that opens "Billie

Jean" or "Bad"?

Maybe Michael Jackson was really trying to tell us something literally when

he sang, "I'm bad, I'm bad, you know it." Or maybe when he

metamorphized into that monster in the "Thriller" video, he was giving us a

glimpse of the horror within. Or maybe he was telling us something even more

personal when he sang: "I'm gonna make a change for once in my life. ... I'm

starting with the man in the mirror. I'm asking him to change his ways. And no

message could have been any clearer. If you want to make the world a better

place, take a look at yourself. And make a change."

Perhaps he was that Man

in The Mirror [YouTube link], who was incapable of taming the monster

within. Perhaps not. All I know is that my heart broke when I heard of his death

on the radio ten years ago this day, and my heart breaks today every time I hear

one of his songs. I can't erase what he did or may have done to those children,

but I am equally incapable of erasing the part his music played in my life. And

so, today, I can only be brutally honest: I highlight one of his recordings as

my "Song of the Day"---"Who

Is It?"---still wondering who he really was, but unflinching in my

appreciation of his artistry.

Posted by chris at 12:04 AM | Permalink |

Posted to Culture | Film

/ TV / Theater Review | Music | Remembrance

Song of the Day #1697

Song of the Day: Summer

of '69 features the words

and music of Jim

Vallance and Bryan

Adams, who recorded this song for his 1984 album, "Reckless." New

York City celebrates the Summer Solstice, which comes to the Northern Hemisphere

at 11:54 a.m. (EDT)---which means that Notablog begins its Fourth Annual Summer

Music Festival (Woodstock

Fiftieth Anniversary Edition). I'm not here to debate the moral

underbelly of the "Apollonian" moon

landing (which, as a child who grew up in awe of the space program, I

will also celebrate in song) versus the "Dionysian"

mudfest that was the Woodstock

Music and Art Fair, as Ayn

Rand once contrasted these events (though Jeff

Riggenbach once called the Woodstock generation among "the

disowned children of Ayn Rand"). This year's festival will run mostly

on a weekly basis from the first to the last day of summer. It will place

special emphasis on the

participating Woodstock artists and the songs they recorded in that

era. With some notable exceptions (marking a few birthdays, for example),

Notablog will also mark the Golden Anniversary of some of the defining events of

the Summer of '69. Our first song is not from that era, but its very title

speaks to the year of our focus---when I was only nine years old---though Adams

himself has long maintained that the number "69" in the title had less to do

with the year and far more to do with a particular love-making position.

This single went to the Top Five on the Billboard Hot

100 in June 1985; check out the Bryan

Adams recording [YouTube link]. As is customary, I will open and

close our annual Music Festival with songs from the same artist, so don't

forget Bryan,

since we'll be returning to him on the last day of summer (it was Chubby Checker who

bookended the 2018 Notablog Summer Music Festival).

Posted by chris at 12:12 AM | Permalink |

Posted to Music | Remembrance

Happy Birthday Cali: The Terrible Twos

Today, the first day of summer, is Cali's birthday. She has now officially

reached the Terrible Twos. But her mischief has been present since the

beginning. Wherever she sits becomes a new place to relax---when she's not

chasing after one of her balls, feathers, or pistachio nutshells. Here are just

a few pics of our little baby doing her own thing.

Open a dresser drawer, and it becomes Cali's bed...

Even bubble wrap becomes Cali's bed...

Even a Petco Plastic Bag becomes Cali's bed...

Is it a bird? A fly? Curious Cali...

Oh... time to wash the dishes!

We wish our little, lovable Cali-co many more happy and healthy returns!

Song of the Day #1696

Song of the Day: Big

City Blues, words and music by Adrienne

Anderson, appears on "2:00

AM Paradise Cafe," Barry

Manilow's fourteenth studio album. In what is one of his best albums,

the artist---who turns 76 today---brings together a host of jazz musicians,

including pianist

Bill Mays, baritone

sax player Gerry Mulligan, drummer

Shelly Manne, bassist

George Duvivier, and guitarist

Mundell Lowe, whose pleasant pickings can be heard at the beginning

and end of today's recording. The 1984

album is one of Manilow's

finest, including the gorgeous "When

October Goes," based partially on an unfinished lyric from the great Johnny

Mercer and a melody

composed by Manilow. The album also includes two wonderful duets: one

with the Divine One, Sarah

Vaughan, and the other---today's Song of the Day---with Mel

Torme, who left us twenty

years ago (June 5, 1999). Check out this Manilow

and Mel duet [YouTube link] in honor of today's

birthday boy.

Posted by chris at 08:35 AM | Permalink |

Posted to Music | Remembrance

The Dialectics of Liberty: About That Cover Design

So I've gotten lots of sweet feedback about the really cool cover design that

was put together for us with the use of Getty images and templates, but a lot of

very nice input from lots of people (Roger found the best image, IMHO), and

especially, Suzanne Hausman.

But take a look at that image. On the surface, it looks like it might be a

person whose chains are broken, and who is liberated---The Dialectics of

Liberty providing the antidote to the corruption of enslavement as

manifested on many levels of generality. And the job of its contributors

exhibits their commitment to exploring the context that would both nourish and

sustain such liberation (even though few of them agree on the precise nature of

that context!).

Take a look at that image a little bit more closely though. The chain links are

going up into the sky... like liberated birds. But wait! It's not a bird! It's

not a plane! It's not even Superman. The links look like they are in the shape

of the letter "M". Could it be that the image itself captures the liberation of

dialectical method from (drumroll please): Its conventional connection to Marxism.

Who knows!? Who knows what you get out of the cover design!?

What matters most is what you'll get when you open the book, and find that there

are essays you'll fall in love with, and other essays that will provoke you to

throw the book (or your e-book device) against the nearest wall! Any book that

can inspire such diametrically opposed reactions with each passing chapter can't

be all that bad!

Lots more to come on the book and its contents; the official release date is

still four days away: June 15, 2019.

Enjoy!

Postcript on Facebook [14

June 2019]:

It has been delightful seeing the flow of pics from contributors to The

Dialectics of Liberty upon receipt of the book, which officially

goes on sale tomorrow. We do have 19 contributors, so I hope the flow of happy

pics will continue. I'm glad I had the ba..., uh, audacity, to start this trend

upon receipt of the volume earlier this week---despite the fact that I looked

like hell (bronchitis, spring allergies, you don't wanna know!). But the "Ben-Hur"

T-shirt did help to hype the epic character of the new book!

To those readers who are suffering sticker shock over the hardcover and e-book

prices, I once again wish to remind you that there is a

30% off discount flyer available. And we encourage interested readers

to make requests to their local public (or private), business, not-for-profit,

university and research libraries to stock up on the book. Yes, a much more

affordable paperback will be issued in early 2020, just in time for our planned

"Authors-Meet-Readers" moderated discussion (which is likely to take place right

here on Facebook). But this is one book worth having, if I may say so myself,

given the diversity of perspectives that it encompasses.

Indeed, I encourage these early celebrations, because the critical blowback

should begin soon. After all, there are not many volumes that will inspire the

reader to fall in love with one chapter, only to be tempted to throw the book

(or their equivalent e-book devices) against the wall in disgust with the very

next chapter. Yet, that's the nature of the "Big Tent" approach of "dialectical

libertarianism," which embraces no single party line; it spurs critical dialogue

among its adherents (indeed, "dialectic" is cognate with "dialogue").

Enjoy!

Postscript (19

June 2019): In a lively discussion of the contents of the book, the contributors

have all been admiring the fact that there is so much "disagreement" in the

volume. Some lamented the absence of essays from contributors who are no longer

with us, like, for example, my dear friend, the late Don Lavoie. I added these

further thoughts, which I share with Notablog readers:

I'm sorry to say that we actually got the rights to include in our collection an

essay by the late Don Lavoie, "The Market as a Procedure for the Discovery and

Conveyance of Inarticulate Knowledge," but as many of you know, we were forced

to go back to the drawing board of our prospectus and cut back dramatically on

previously published essays. Don was a very dear friend of mine and a

trailblazing thinker. But with Lavoie's essay ending up on the cutting-room

floor, I deeply appreciated Nathan Goodman's contribution to our volume!

Only three previously published essays exist in our collection and at least two

of them were reworked for the anthology (the essays by Stephan Kinsella and

Deirdre McCloskey). While many of the other essays summarize points of

previously published works, the bulk of them are original to the volume. And lo

and behold, Roderick Tracy Long is right: There is no massive agreement among

those who think dialectically in this volume. Which makes this a living project

... open to much growth in the future! All of you here made that possible and I

can't thank you folks enough for all the work you did.

There really is a treasure trove of material that could be anthologized in a

collection of Don Lavoie's essays. Aside from being a very dear friend of mine,

Don and I had somewhat parallel paths while we were at NYU: he was in the

Economics Department pursuing a Ph.D. with Austrian economist Israel Kirzner as

his dissertation advisor and Marxist James Becker on his dissertation committee;

I was in the Politics Department pursuing a Ph.D. with Marxist Bertell Ollman as

my dissertation advisor and Austrian economist Mario Rizzo on my dissertation

committee. Don not only encouraged my work with dialectical method, but was

probably the very first professor to adopt one of my books (Marx, Hayek, and

Utopia) for one of his courses on Comparative Economic Systems.

Posted by chris at 12:10 PM | Permalink |

Posted to Austrian

Economics | Dialectics | Frivolity

JARS: The New July 2019 Issue and A New Website

It is with great pleasure that I announce today not only the contents of the new

July 2019 issue of The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies, but the debut of our

new home page!

The journal made its first appearance in the early Fall of 1999, so, technically,

we are entering our twentieth anniversary year; but we are beginning our

nineteenth volume with a July issue that provides some hefty discussions of some

very interesting philosophical issues. With our December 2019 issue already in

the works, we are, in fact, planning out our two 2020 issues, which will

officially mark our twentieth anniversary. Imagine that!

We are actually approaching two decades of providing a double-blind,

peer-reviewed, interdisciplinary, biannual, university-press-published (since

2013) periodical focused on Ayn Rand and her times. When Bill

Bradford proposed this idea to me more than twenty years ago, I

thought he was crazy! But here we are... moving forward still, with a journal

that provides a safe scholarly haven for people coming from remarkably different

critical and interpretive perspectives, covering virtually every aspect of Rand

studies imaginable---from nitty-gritty discussions on Rand's ethics and aesthetics to

engagement on "Rand

among the Austrians" and enlightening

dialogue over the cultural impact of Rand on progressive rock!

Back in 2016, when we published our first double issue (the first book-length

symposium on "Nathaniel

Branden: His Work and Legacy"), we unveiled a brand-new website,

re-designed by our original webmaster, Michael Southern, who had been with us

from the beginning. Michael was a dear friend of nearly forty years and

transformed our original site with a custom-made template for a new site that

made its debut with that symposium. Michael actually provided a centerpiece

essay in that symposium, "My

Years with Nathaniel Branden," which told the very personal story of

his relationship with Branden, first as a client, then as an intern and

associate, and, finally, as a friend.

Sadly, tragically, my

dear friend was killed in September 2017. With his death, so too died

the custom template he developed for our website. He was poised to re-do my own

home page, and told me we had "time" for him to share the JARS template with me

so that I could easily update it on my own. Alas, we took much for granted. With

Michael gone, I tried to maintain the site, but found it increasingly difficult.

I count my blessings that I have come to know many beautiful, honorable, decent,

kind, and generous human beings in my life; Michael was one of them.

So too is my dear friend Peter

Saint-Andre, who stepped up and completely re-constructed the site,

retaining aspects of Michael's design, integrated into a new template, knowing

full well that we required a practical plan moving forward for the years to

come. I truly cannot quite find the words that would adequately express just how

deeply I appreciate Peter's hard work throughout all these months. He is truly a

Saint(-Andre)!

JARS readers will recall Peter's long-time relationship with the journal as

well. He contributed essays as far back as Volume

4 (2002-2003) ("Conceptualism in Abelard and Rand"; "Zamyatin and

Rand"); Volume

5 ("Saying Yes to Rand and Rock," a contribution to the journal's

symposium, "Rand, Rush, and Rock"); Volume

7, Number 2 ("Image and Integration in Ayn Rand's Descriptive

Style"); Volume

9, Number 1 ("Ayn Rand, Novelist"---a review of The Literary Art

of Ayn Rand); and Volume

10, Number 2 ("Nietzsche, Rand, and the Ethics of the Great Task," a

contribution to the journal's "Symposium on Friedrich Nietzche and Ayn Rand").

In fact---of great interest to this particular editor, with Peter's current

program of deep research into Aristotle (see here,

for details), his interests extend to the role of dialectic in Aristotle and how

it compares with dialectical libertarianism.

Take a look at the new site and all that it has to offer. Welcome back to: The

Journal of Ayn Rand Studies.

And while you're visiting, take a look at the new July 2019 issue!

The abstracts for the essays in the new issue can be found here and

the Contributor Biographies can be found here.

Here is the Table of Contents of the new issue:

Foundational Frames: Descartes and Rand - Stephen Boydstun

Ayn Rand's Credit Problem - Lamont Rodgers

Ayn Rand and the Lost Axiom of Aristotle: A Philosophical Mystery---Solved? -

Roger E. Bissell

The Return of the Arbitrary: Peikoff's Trinity, Binswanger's Inferno, Unwanted

Possibilities---and a Parrot for President - Robert L. Campbell

As I have vowed since the very first issue of this journal, every issue would

bring aboard at least one new contributor to the JARS family of authors. This

issue, it is Lamont Rodgers whom we welcome to our pages. And we thank each of

the contributors for providing such thought-provoking essays as we begin our

nineteenth volume.

I would like to remind prospective contributors to submit their original essays

through our Editorial

Manager interface provided by Pennsylvania State University Press.

And those looking to subscribe to print and/or online editions of the journal

can find additional information here.

The new issue will soon be making its debut on JSTOR and Project Muse, with

print copies going out to subscribers in the weeks to come.

My thanks to all of those who have supported this journal through the years. We

are happy to be entering a new phase of our development.

Posted by chris at 12:02 AM | Permalink |

Posted to Periodicals | Rand

Studies | Remembrance

Song of the Day #1695

Song of the Day: The

Music Man ("Seventy-Six Trombones"), music and lyrics by Meredith

Wilson, is one of the rousing highlights from this 1957

Tony Award-winning musical, starring Robert

Preston (who won for Best

Performance by a Leading Actor in a Musical) and Barbara

Cook (who won for Best

Performance by a Featured Actress in a Musical). The cast album would

go on to win a Grammy

Award for Best Musical Theater Album. In October 2020, a

revival of the musical, starring the irrepressible Hugh

Jackman, will make its debut on Broadway. (Jackman actually

performed "Rock

Island" [YouTube link] with LL

Cool J and T.I. on

the 2014

Tony Awards, giving us a glimpse into the "rap" nature of one of the

classic opening numbers to the musical!) Check out the

original Broadway cast version of today's song from the musical and the

1962 film version [YouTube links], both led by the great Robert

Preston. And I'm one to enjoy

even one [YouTube link], let alone seventy-six, trombones. Enjoy the Tony

Award's celebration of the Broadway stage tonight!

Posted by chris at 12:02 AM | Permalink |

Posted to Film

/ TV / Theater Review | Music

It Arrived!

It Arrived!

My New Ben-Hur T-Shirt!

Oh, and so did my very first hardcover copy of The

Dialectics of Liberty: Exploring the Context of Human Freedom,

co-edited with my friends and colleagues Roger

E. Bissell and Edward

W. Younkins.

Don't laugh. I'm trying to stand still in that photo, and not to Jump,

Jive, an' Wail!

Posted by chris at 04:52 PM | Permalink |

Posted to Dialectics | Education | Frivolity | Periodicals | Politics

(Theory, History, Now)

Song of the Day #1694

Song of the Day: Cabaret

("Maybe This Time"), music by John

Kander, lyrics by Fred

Ebb, was one of the winning songs not included in the original 1966

Broadway musical, which nonetheless won a total of eight

out of the eleven Tony Awards for which it was nominated: Best

Musical, Best

Direction of a Musical, Best

Original Score, Best

Performance by an Actor in a Featured Role (Joel

Grey), Best

Performance by an Actress in a Featured Role (Peg

Murray), Best

Choreography, Best

Scenic Design, and Best

Costume Design. I wasn't fortunate enough to see the original

Broadway production, but I did see its

absolutely spectacular 1998 revival, which won Tony Awards for Best

Revival of a Musical, Best

Performance by a Leading Actor in a Musical (the stupendous Alan

Cumming), Best

Performance by a Leading Actress in a Musical (Natasha

Richardson), and Best

Performance by an Actor in a Featured Role (Ron

Rifkin)---four awards out of a total of an additional ten

nominations. The musical derives from the 1951 play, "I

Am a Camera," which itself was adapted from the short story by Christopher

Isherwood, Goodbye

to Berlin. This song made its way from the film into the musical

revival and it remains one of its highlights, sung by the character Sally

Bowles. Check out the rendition sung by Natasha

Richardson in the 1998 reboot, and, of course, the Oscar-winning

Best Actress performance of Liza Minelli [YouTube links], in the Bob

Fosse-directed 1972 film adaptation. Today starts a two-day tribute

to the 2019

Tony Awards, hosted by James

Corden, which will air on Sunday, June 9th, on the CBS

Network.

Posted by chris at 09:25 AM | Permalink |

Posted to Film

/ TV / Theater Review | Music

Song of the Day #1693

Song of the Day: Le

Grind, composed by Prince,

is from his "Black

Album" (aka "The

Funk Bible"), which was recorded in 1986-87, but not released until

1994, largely because the artist believed it was created under the influence of

an "evil"

demonic entity "Spooky

Electric." With all honesty, it's hard to figure out precisely what

was so evil about this funk-heavy track with the same sensuous lyrics we'd all

come to expect from The

Artist. Despite his tragic

death in 2016, his music lives on. Today would have been his

sixty-first birthday. Check out the rare

track on YouTube.

Posted by chris at 06:01 AM | Permalink |

Posted to Music | Remembrance

Song of the Day #1692

Song of the Day: I

Love You, words

and music by Cole

Porter, was the #1

song on this day, June

6, 1944, for the fifth week in a row, as sung by Bing

Crosby with John

Scott Trotter and His Orchestra. The song came from Porter's

1944 stage musical "Mexican

Hayride." It was first recorded by Wilbur

Evans (who played the character David) in that musical, but it was Bing

Crosby's recording of the song that took it to the top of the charts.

This weekend, other musicals will be honored at the Tony

Awards. But it is of particular interest that the American public had

embraced a sentimental song of love for the five weeks leading up to the

Allied invasion of Normandy, the largest air, land, and sea invasion

in human history that proved to be the beginning of the end of World

War II. That war, which led to estimated fatalities of 70 to 85

million people, may have signified the "nadir

of the Old Right"---but it also brought forth the intellectual seeds

of a libertarian resurgence in the decades to come. Nevertheless, I post this

song today as an expression of love to my

own family members who fought and

died in that most horrific of wars, and in honor of those who survived that

battle on the beaches of Normandy,

and who have returned to those beaches today, to mark the seventy-fifth

anniversary of that invasion, knowing that, in the words of Herman

Wouk: "The

beginning of the end of war lies in remembrance." Check out the

original Wilbur Evans version of this song and the

#1 Bing Crosby hit [YouTube links] that serenaded Americans at home,

who listened to the music on the radio, with news bulletins that, they prayed,

would move the world one step closer to peace.

Posted by chris at 09:59 AM | Permalink |

Posted to Culture | Film

/ TV / Theater Review | Foreign

Policy | Music | Politics

(Theory, History, Now) | Remembrance