![]()

![]()

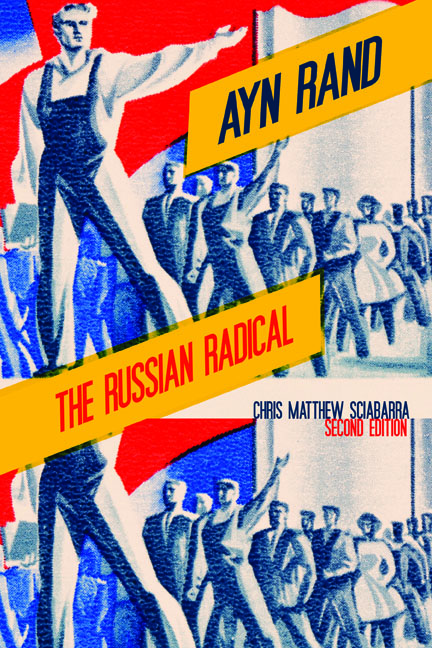

THE 2013 SECOND EDITION

BLOG POST #1: RUSSIAN RADICAL 2.0: THE COVER (12 August 2013)

In the course of the next week, I am marking the publication of the second edition of Ayn Rand: The Russian Radical, offically scheduled for release on "Atlas Shrugged Day", 2 September 2013—though in this home, we have always known that date as my sister's birthday. Nevertheless, more likely than not, the book will be circulating by the end of September or early October. Published nearly two decades ago, the first edition is actually celebrating its 18th anniversary this month. Also reaching its 18th birthday, my first book: Marx, Hayek, and Utopia. Tomorrow, I'll provide "The Cover Story," and I'll lots to say about both books.

Today, it's just The Cover. Over the next few days, we'll have the opportunity to explore the differences between the first and second editions of the book. But the clearest and boldest symbol of difference is the cover. The 1995 first edition cover design by Steve Kress provided images of Ayn Rand, philosophy Professor N. O. Lossky, and the Peter and Paul Fortress, where, in 1924, the young Ayn Rand (nee Alissa Rosenbaum) lectured on the fortress's history.

.jpg)

The second edition's cover design is, if you'll pardon the expression, quite a radical departure from the first edition. Those familiar with Ayn Rand will recall that her original working title for the book that was to become her magnum opus, Atlas Shrugged, was simply: "The Strike." Considering how strikes were customarily tools of organized labor, Rand was engaging in the kind of linguistic subversion that was characteristic of one of her earliest philosophic influences, Friedrich Nietzsche. Rand would often use words associated with negative connotations, and totally invert their meaning. Hence, for Rand, there was a "virtue" of selfishness and capitalism was not a system of exploitation, but an "unknown ideal." Well, in this instance, her working title for Atlas Shrugged was her way of using a word, "Strike", typically associated with worker revolts against "greedy" capitalists. For Rand (spoiler alert), Atlas Shrugged explores what happens when "the men of the mind" go on strike, when men and women, mostly innovative business leaders, no longer wish to sanction their own victimhood. The new cover uses the strike imagery in the color scheme of the country to which Rand emigrated in 1926 (the red, white, and blue of the U.S. flag), while also using banners with touches of red (the background of the Soviet flag) and yellow (the color of that flag's "hammer-and-sickle"). Over the next few days, we'll have an opportunity to delve into the back story of how this second edition took form. Thanks to the design team at Pennsylvania State University Press, today, it's all about the cover!

BLOG POST #2: RUSSIAN RADICAL 2.0: THE COVER STORY (13 August 2013)

It was around the second or third week of August 1995, that both Marx, Hayek, and Utopia and Ayn Rand: The Russian Radical made their first appearance, providing the illusion that this author would be the kind of prolific writer who would be publishing two books a week for the rest of his career. (Okay, okay, I didn't do too badly... but still!)

From the very beginning, however, these two books were conceived as part of a trilogy, which would seek to reclaim dialectics ("the art of context-keeping") in the service of a radical libertarian politics. The scheme of that trilogy came about in the planning stages of my doctoral dissertation in political philosophy, theory, and methodology at New York University, where I earned my Ph.D. under the direction of Marxist scholar, Bertell Ollman. There have been few scholars on the left or the right who encouraged me in my work on libertarianism as much as did this dear friend and colleague. "Toward a Radical Critique of Utopianism: Dialectics and Dualism in the Works of Friedrich Hayek and Karl Marx" was completed and successfully defended with distinction in 1988. Two parts of that dissertation---those focusing on Marx and Hayek---became the basis of Marx, Hayek, and Utopia, which was readied and planned for publication in 1989-90 by Philosophia Verlag, a West German publishing house that met its extinction around the time that West Germany itself ceased to exist. (The third part of the dissertation, which focused on the work of the great Murray Rothbard, was revised and expanded considerably, and was later incorporated as part of the culminatinating book of my "Dialectics and Liberty Trilogy": Total Freedom: Toward a Dialectical Libertarianism.)

With the Marx-Hayek book put on hold temporarily, I decied to begin work on what was to become the second part of the trilogy. And so began the massive historical and methodological research project that eventually became Ayn Rand: The Russian Radical. Rejected by many university presses who dismissed Rand as a figure not worthy of "scholarly" treatment, and by many trade presses who dismissed a book about a "pop" novelist and "philosopher" as being too scholarly, it eventually found a home with Pennsylvania State University Press. With the brilliant guidance of its director Sanford ("Sandy") Thatcher, the book began the process of dragging academia and Rand's "non-academic" Objectivist philosophy "kicking and screaming" into engagement with one another.

After a wonderful run of seven paperback printings, the book was one of the all-time Penn State Press sales champs.

Then, in 2012, the new director of Penn State Press, Patrick Alexander, had an inspired idea to re-release the book in an expanded second edition. More on that below.

In the meanwhile, Marx, Hayek, and Utopia finally found its own home at an American university press (the State University of New York Press), and was published officially on 23 August 1995. And though the official date of publication for Russian Radical is listed as 19 June 1995, take it from me: both books finally made their way from their respective warehouses to my house in the same week of August 1995. It was an odd coincidence, indeed, to have two books come out simultaneously, but it only made the intensive research and writing of the trilogy's finale, Total Freedom (published officially on 2 November 2000), all the more intellectually urgent to me I knew that the first two books would generate even more questions that could only be answered by re-reading the history of dialectics and providing a definition of it that would make sense in the context of the radical libertarian political project to which I'd been aligned.

In the nearly two decades since the publication of the first two books of my "Dialectics and Liberty Trilogy," other projects, of course, took up enormous chunks of my time and intellectual energy; in 1999, I co-edited with Mimi Reisel Gladstein, Feminist Interpretations of Ayn Rand and became a founding co-editor of The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies. I wrote a couple of monographs, scores of articles for books, journals, magazines, and encyclopedias, and was deeply involved in online discussion forums for a long time, until I decided that there were only so many hours in a day, and opted to focus exclusively on my own work done my own way. That included the development of my own blog (Notablog) and a focus on expanding the breadth, depth, and quality of The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies (JARS).

And so, when I was approached last year by Penn State Press director, Patrick Alexander, to begin a colalborative publishing project with the press, I jumped at the chance; after all, it would allow the editors of JARS to focus 100% of our energy on editorial functions and would give the press control over the business aspects of the journal (design, page proof preparation, additional copyediting, printing, subscription fulfillment, and mailing), which were absorbing endless hours of my time.

The first Penn State Press issue of the journal, Volume 13, Number 1 (July 2013) was just published (it's actually fulfilled in an arrangement with Johns Hopkins University Press), and our year-end edition, scheduled for December 2013, will include nearly double the number of articles as the first. I would say that we are receiving now a record level of submissions.

But Patrick had other ideas too; he thought it was about time to publish a second edition of Ayn Rand: The Russian Radical. I had done very intensive research into Rand's education after my 1995 book was published, and two of the articles documenting my research were actually published in The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies. So strong was the evidence, in my view, in support of my overall historical thesis that Rand learned from and was heavily exposed to the dialectical methods central to the cultural milieu of that particular place (Russia) and time (pre-and-post revolutionary), that I agreed: these essays needed to appear in a second edition, where they would get the kind of exposure they deserved.

So our plan was to include these two articles, plus a new "Preface to the Second Edition," which would enable me to situate the work in the larger universe of expanding Rand studies, and in the particular context of my own dialectical-libertarian project. Soon enough, however, we'd added a third appendix, enabling me to answer a recent critic of my historical research into Rand's education. And then they gave me the opportunity to tweak the book from cover to cover, updating some of the scholarship, and, along the way, adding a much-expanded section of Chapter 12 ("The Predatory State") dealing with Rand's radical critique of the welfare-warfare state, so relevant to a post-9/11 generation. The book was re-keyed, the index was expanded, and before too long, an e-book will be in the offing.

Tomorrow, in my next blog post on Russian Radical 2.0, I'll be discussing some of the specific differences between the first and second edition.

BLOG POST #3: RUSSIAN RADICAL 1.0 VERUS 2.0: WHAT'S DIFFERENT? (14 August 2013)

The 2013 expanded second edition of Ayn Rand: The Russian Radical offers a vastly expanded content over its 1995 predecessor. I have written a "Preface to the Second Edition," which I will publish here tomorrow; I have added three appendices. The first two are reprints of two essays that previously appeared in The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies: "The Rand Transcript" (1999) and "The Rand Transcript, Revisited" (2005). A third appendix answers the recent criticisms made by Shoshana Milgram in an essay of hers that was pubished in the second edition of Robert Mayhew's edited collection, Essays on Ayn Rand's "We the Living." Milgram, who is Rand's newest "authorized" biographer, actually makes the case that Rand did not study with N. O. Lossky, as I've contended, and that Rand herself contended, not only in the private interviews she conducted with Nathaniel Branden and Barbara Branden, but in the only biographical essay published about her in her own lifetime: "Who is Ayn Rand?" by Barbara Branden, which appears in the 1962 book of the same title. Needless to say, I provide what I believe is a defense not only of Russian Radical's historical thesis but of the authenticity and integrity of Rand's own recollections.

A comparison of the content of the 1995 first edition of my book to the newly expanded 2013 second edition can be found in the Table of Contents page of my Russian Radical site.

BLOG POST #4: RUSSIAN RADICAL 2.0: THE PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION (15 August 2013)

Recently published on the Pennsylvania State University Press site is a sample chapter from the new 2013 second edition of Ayn Rand: The Russian Radical. Today, I publish that excerpt here, on Notablog.

Preface to the Second Edition (2013)

Nearly twenty years ago, Ayn Rand: The Russian Radical was published. In its wake came much controversy and discussion, which greatly influenced the course of my research in subsequent years. In 1999, I co-edited, with Mimi Reisel Gladstein, Feminist Interpretations of Ayn Rand, part of the Pennsylvania State University Press series on Re-Reading the Canon, which now includes nearly three-dozen volumes, each devoted to a major thinker in the Western philosophic tradition, from Plato and Aristotle to Foucault and Arendt. In that same year, I became a founding co-editor of the Journal of Ayn Rand Studies, a biannual interdisciplinary scholarly journal on Ayn Rand and her times that, in its first twelve volumes, published over 250 articles by over 130 authors. In 2013, the journal began a new collaboration with the Pennsylvania State University Press that will greatly expand its academic visibility and electronic accessibility

It therefore gives me great pleasure to see that two essays first published in the Journal of Ayn Rand Studies---"The Rand Transcript"---and "The Rand Transcript, Revisited"---have made their way into the pages of the second, expanded edition of this book, providing a more complete record of the fascinating historical details of Rand's education from 1921 to 1924 at what was then Petrograd State University.

In publishing the second edition of any book written two decades ago, an author might be tempted to change this or that formulation or phrase to render more accurately its meaning or to eliminate the occasional error of fact. I have kept such revisions to a minimum; the only extensively revised section is an expanded discussion in chapter 12 of Rand's foreign policy views, relevant to a post-9/11 generation, under the subheading "The Welfare-Warfare State." Nevertheless, part of the charm of seeing a second edition of this book published now is being able to leave the original work largely untouched and to place it in a broader, clarifying context that itself could not have been apparent when it was first published.

My own Rand research activities over these years are merely one small part of an explosive increase in Rand sightings across the social landscape: in books on biography, literature, philosophy, politics, and culture; film; and contemporary American politics, from the Tea Party to the presidential election

Even President Barack Obama, in his November 2012 Rolling Stone interview, acknowledges having read Ayn Rand:

"Ayn Rand is one of those things that a lot of us, when we were 17 or 18 and feeling misunderstood, we'd pick up. Then, as we get older, we realize that a world in which we're only thinking about ourselves and not thinking about anybody else, in which we're considering the entire project of developing ourselves as more important than our relationships to other people and making sure that everybody else has opportunity---that thats a pretty narrow vision. It's not one that, I think, describes what's best in America."

The bulk of this book predates the president's assessment, and yet it is, in significant ways, a response to assessments of that kind. First and foremost, it is a statement of the inherent radicalism of Rand's approach. Her radicalism speaks not to the alleged "narrow vision" but to the broad totality of social relationships that must be transformed as a means of resolving a host of social problems. Rand saw each of these social problems as related to others, constituting---and being constituted by---an overarching system of statism that she opposed. My work takes its cue from Rand, and other thinkers in both the libertarian tradition, such as Ludwig von Mises, F. A. Hayek, and Murray N. Rothbard, and the dialectical tradition, such as Aristotle, G. W. F. Hegel, Karl Marx, and Bertell Ollman. From these disparate influences, I have constructed the framework for a "dialectical libertarianism" as the only fundamental alternative to that overarching system of statism. In this book, I identify Rand as a key theorist in the evolution of a "dialectical libertarian" political project.

The essence of a dialectical method is that it is "the art of context-keeping." More specifically, it emphasizes the need to understand any object of study or any social problem by grasping the larger context within which it is embedded, so as to trace its myriad---and often reciprocal---causes and effects. The larger context must be viewed in terms that are both systemic and historical. Systemically, dialectics demands that we trace the relationships among seemingly disparate objects of study or among disparate social problems so as to understand how these objects and problems relate to one another---and to the larger system they constitute and that shapes them. Historically, dialectics demands that we trace the development of these relationships over time---that is, that we understand each object of study or each social problem through its past, present, and potential future manifestations.

This attention to context is the central reason why a dialectical approach has often been connected to a radical politics. To be radical is to "go to the root." Going to the "root" of a social problem requires understanding how it came about. Tracing how problems are situated within a larger system over time is, simultaneously, a step toward resolving those problems and overturning and revolutionizing the system that generates them.

The three books in my "Dialectics and Liberty trilogy"---of which Ayn Rand: The Russian Radical is the second part---seek to reclaim dialectical method from its one-sided use in Marxist thought, in particular, by clarifying its basic nature and placing it in the service of a radical libertarianism

The first book in my trilogy is Marx, Hayek, and Utopia, which I published in 1995 with the State University of New York Press. It drew parallels between Karl Marx, the theoretician of communism, and F. A. Hayek, the Austrian "free market" economist, by highlighting their surprisingly convergent critiques of utopianism and their mutual appreciation of context in defining the meaning of political radicalism

Ayn Rand: The Russian Radical, the second book in the trilogy, details the approach of a bona fide dialectical thinker in the radical libertarian tradition, who advocated the analysis of social problems and social solutions across three distinctive, and mutually supportive, levels of generality---the personal, the cultural, and the structural (see especially "The Radical Rand," part 3 of the current work).

The third book and final part of the trilogy, Total Freedom: Toward a Dialectical Libertarianism, was published in 2000 by the Pennsylvania State University Press. It offers a rereading of the history of dialectical thinking, a redefinition of dialectics as indispensable to any defense of human liberty and as a tool to critique those aspects of modern libertarianism that are decidedly undialectical and, hence, dangerously utopian in their implications.

That my trilogy places libertarian thinkers within a larger dialectical tradition has been resisted by some of my left-wing colleagues, who view Marxism as having a monopoly on dialectical analysis, and some of my right-wing colleagues, who are aghast to see anybody connect a libertarian politics to a method that they decry as "Marxist," and hence anathema to the project for liberty. Ironically, both the left-wing and right-wing folks who object to my characterization of a dialectical libertarian alternative commit what Rand would have called "the fallacy of the frozen abstraction." For Rand, this consists of substituting some one particular concrete for the wider abstract class to which it belongs. Thus, the left-wing and right-wing critics both freeze and reduce the concept of dialectical method to the subcategory of one of its major historical applications (i.e., Marxism). They both exclude another significant subcategory from that concept, whether to protect the favored subcategory (as do some conservatives, libertarians, and Objectivists) or the concept itself (as do the leftists). Ultimately, they both characterize dialectics as essentially Marxist. It is as if any other variety of dialectics does not or cannot exist. In each case, the coupling of dialectics and libertarianism is denied. The left-wing dialecticians don't want to besmirch "their" methodology by acknowledging its presence in libertarian thinking, while the right-wing proponents of liberty don't want to sully their ideology with a "Marxist" methodology.

But as I have demonstrated in my trilogy, especially in Total Freedom, it is Aristotle, not Hegel or Marx, who is the "fountainhead" of a genuinely dialectical approach to social inquiry. Ultimately, my work bolsters Rand's self-image as an essentially Aristotelian and radical thinker. In doing so, my work challenges our notion of what it means to be Aristotelian and radical.

I am cognizant that my use of the word "dialectics" to describe the "art of context-keeping" as a vital aspect of Rand's approach to both analyzing problems and proposing highly original, often startling solutions, is controversial. My hypothesis---in this book and in the two additional essays that now apear as appendices I and II of this expanded second edition---that Rand learned this method from her Russian teachers has generated as much controversy. Rand named N. O. Lossky as her first philosophy professor. Questions of the potential methodological impact on Rand that Lossky and her other Russian teachers may have had, and the potential discrepancies between Rand's own recollections with regard to Lossky and the historical record, were all first raised in Russian Radical. These issues, nearly twenty years after they were raised, have resulted in Rand's prospective "authorized" biographer arguing that Rand's recollections were mistaken. In my view, however, this turn in historical interpretation is itself deeply problematic. I discuss these issues in a new essay, which appears as appendix III, "A Challenge to Russian Radical---and Ayn Rand."

I am genuinely excited that the Pennsylvania State University Press has enabled me to practice what I dialectically preach: placing Russian Radical and its cousins in the larger context both of my research on Rand and of my Dialectics and Liberty trilogy enables me to present readers with a clearer sense of what I have hoped to accomplish. Thanks to all those who have made this ongoing adventure possible.

Chris Matthew Sciabarra

1 July 2013

[Notes and in-text citations have been eliminated from the above excerpt; they can be found in the new expanded second edition of this book.]

BLOG POST #5: RUSSIAN RADICAL 2.0: SUPPLYING ANSWERS, RAISING QUESTIONS (16 August 2013)

This week's discussion of the forthcoming publication of the new, expanded second edition of Ayn Rand: The Russian Radical has provided me with an avalanche of enthusiastic feedback from many people. I hope to answer the email in time, but I just wanted to thank everyone for a show of support. (And a shout out especially to Danny at Penn State Press for his nice blog post on this week's Notablog festivities. He states there: "There you have it, folks: linguistic subversion. Pretty appropriate when you consider Chris Sciabarra's blog is called 'Notablog,' don't you think? This second edition of Ayn Rand adds two chapters that provide in-depth analysis of the most complete transcripts to date documenting Rand’s education at Petrograd State University. It includes a new preface that places the book in the context of Sciabarra’s own research and the recent expansion of interest in Rand’s beliefs. And finally, this edition adds a postscript that answers a recent critic of Sciabarra’s historical work on Rand. For more on Ayn Rand: The Russian Radical keep checking Notablog, where Chris will be posting details about the book all week long.)BLOG POST #6: RUSSIAN RADICAL 2.0: 12 SEPTEMBER 2013 RELEASE DATE (2 September 2013)

Last month, I

announced the publication of the second expanded edition of Ayn Rand: The Russian Radical.

I didn't have the opportunity to thank Paul Hornschemeier, for designing a

cover that is as fresh as the content to be found in the new edition; here is a

snapshot of the front and back cover design:

The book's official release

date is now 12 September 2013. I look forward to seeing the final product

myself!

BLOG POST #7: RUSSIAN RADICAL 2.0: IT HAS ARRIVED (12 September 2013)

As I've been discussing in various entries on Notablog (see the introductory

discussion that begins

here), the date of publication for the new expanded second edition of

Ayn Rand: The

Russian Radical was shifted from 2 September 2013 to 12 September 2013,

which means that today, this author has given birth to a twin (albeit 18 years

after the first of the twins). Oh, it's not quite a twin (trace the differences

here), but

like all my books, it's always exciting to see one of my babies make it into the

world, even if in reincarnated form.

I see that it is now to be found at

Penn State

Press,

Amazon.com, and it is mentioned by Irfan Khawaja on the website of his

exciting new project, which has resurrected a familiar name, while taking things

into a provocative new direction:

the Institute for Objectivist Studies.

I've not yet received the

book, but it was to arrive at the warehouse today... which means, the bouncing

baby book will reach me soon, and I'm looking forward to holding it in my arms.

BLOG POST #8: RUSSIAN RADICAL 2.0: A KINDLE EDITION AND REVISED REVISIONS (8 January 2014)

I recently published a Notablog series on "Russian Radical 2.0" as I've called it: the newly published second edition of Ayn Rand: The Russian Radical:

BLOG POST #9: RUSSIAN RADICAL 2.0: REVIEWS AND RETROSPECTIVES (7 August 2015)

BLOG POST #10: RUSSIAN RADICAL 2.0: THE THREE Rs (18 July 2016)

Today's post will discuss the Three Rs, as they relate, ironically, to the second edition of my book, Ayn Rand: The Russian Radical: Reviews, Rand Studies, and Rape Culture.

As readers of Notablog know, my 1995 book, Ayn Rand: The Russian Radical, went into a grand second edition in 2013, on the eve of its twentieth anniversary (readers can see all the blog posts related to the second edition on a new page added to the Russian Radical site). As is the fate of most second editions, even vastly expanded ones like the current book, few reviews seem to surface. But it has been a pleasant surprise to see that the book has made an impact on the ever-growing Rand scholarly literature. I have updated the review section of the Russian Radical page to reflect some of the reviews and discussions of the book in that literature. My own reply to critics ("Reply to Critics: The Dialectical Rand") will not appear until July 2017 in The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies (Volume 17, no. 1). The delay in that reply has been primarily due to the fact that we, at the journal, have been working relentlessly on what promises to be, perhaps, the most important issue ever published by JARS: a double-issue symposium, due out in December 2016 (Volume 16, nos. 1-2): "Nathaniel Branden: His Work and Legacy." It is a book-length version of the journal that will be print published and available online through JSTOR and Project Muse, and to those who wish to purchase single print copies or single copies of the first e-book and Kindle editions of JARS ever published. We are proud of the final product, which includes sixteen essays by people coming from a wide diversity of disciplines and perspectives, including political and social theory, philosophy, literature, film, business and leadership, anthropology, and, of course, academic and clinical psychology. It also includes the most extensive annotated bibliography of Branden works and of the secondary literature mentioning Branden yet published.

What makes this issue so

important is that it will bring to a wider audience the work of many writers who

have never appeared in any Rand-oriented periodical, while also bringing

attention to the work and legacy of Branden to the community of clinical and

academic psychologists.

It is an issue that only JARS could have

produced.

Such a study would never come forth from the

"orthodox" Objectivists, who have virtually airbrushed even Branden's canonic

contributions to Objectivism out of existence (the new Blackwell

Companion

to Ayn Rand a notable exception), or from the established orthodoxies of

the psychological community who have dismissed Branden's work as "pop"

psychology--in much the same way that the established scholarly orthodoxies

locked out Rand from the Western canon by referring to her as a cult-fiction

writer and pop philosopher, an attitude that has slowly been eroded over the

years by increasingly serious work on her corpus, something to which JARS has

contributed with pride.

In any event, readers can find

excerpts from some of the commentaries made on

Russian Radical in the recent

scholarly literature by checking the updated review pages

here.

Ironically, among the reviewers is Wendy McElroy, who discussed Russian Radical in the pages of JARS (in a review that appeared in the July 2015 issue). I'm happy that Wendy had the opportunity to review the book, given that she has been so hard at work on so many worthwhile projects. One of those projects was just published: a truly provocative new book, entitled Rape Culture Hysteria: Fixing the Damage Done to Men and Women. I've just posted a mini-review of the 5-star book on amazon.com; here is what I had to say (which relates directly to my view of "The Dialectical Rand"):

Wendy McElroy's new book, Rape Culture Hysteria: Fixing the Damage Done to Men and Women, is certainly one of the most provocative books on this subject ever written. The freshness with which McElroy approaches the subject is in itself controversial, though it is hard to believe that approaching any subject with reason as one's guide could possibly be controversial.

Whether one agrees or disagrees with any particular point made by McElroy, what she accomplishes here is to show the power of a nearly all-encompassing ideology to corrupt the very subject it seeks to make transparent.The power of her analysis lies in the intricate ways in which she approaches not only the problems of rape culture ideology but in the documentation and analysis that she uses to undermine many of the arguments that its proponents put forth to support their various positions. It is a startling display of analytical power so strong that it must challenge people on all ends of the political spectrum.

The sad part of the Politically Correct doctrine of the "rape culture," however, is that it actually undermines the power of some doctrines that I, as a social theorist, accept, with provisos.For example, the doctrine that "the personal is the political," rejected with good reason by McElroy, is used by PC feminists in a way that does not illuminate the mutual implications of the personal and the political; rather, it folds everything personal into the political. That such a doctrine could have emerged out of postmodern New Left thought is doubly disturbing, however, given the Marxist penchant for so-called "dialectical" analysis, that is, analysis that aims to grasp the wider context of social problems by tracing their common roots and multidimensional manifestations and undermining them in a radical way. The same penchant exists, in my view, among many of those in the libertarian and individualist traditions, including in the work of the self-declared "anti-feminist" Ayn Rand, who, for all her anti-feminism, may have done more to empower women than any PC feminist could have ever dreamed… this, despite her views of man-woman relationships or of homosexuality, both of which one can take issue with, while not doing fundamental damage to her overall philosophic system.

The fact is that even Rand believed that there were mutual implications between the personal and the political; one's view of oneself, how one uses one's mind, the methods of one's thinking processes (so-called "psycho-epistemology", etc.) and the origins of the doctrine of self-esteem, and of the self-esteem movement championed by her protege, Nathaniel Branden, show how certain cultural, educational, and political institutions have virtually conditioned individuals to accept authority and certain destructive ideologies in ways that ultimately undermine their ability to think as individuals and accept self-responsibility, thus paving the way for the rule of coercive political power. Rand and her intellectual progeny have grasped these phenomena by showing how they operate in mutually reinforcing ways across disciplines and institutions within a system, and across time.

I don't think McElroy would

disagree with this, even if she fundamentally questions the doctrine of "the

personal is the political," for she, herself, shows that there are indeed both

personal and political consequences to the ways in which that doctrine is used

by its so-called champions.

But that is the kind of fundamental rethinking

McElroy's book provokes for any reader who approaches her work with a critical

mind.

Bravo!

BLOG POST #11: RUSSIAN RADICAL 2.0: THE RAND-MARX PARALLELS (1, 8 October 2016)

The second edition of

Ayn Rand: The

Russian Radical has continued to spur discussion in print media and

online. I will be responding to many of the commentators in a forthcoming essay,

"Reply to Critics: The Dialectical Rand," which will be published in the July

2017 issue of The

Journal of Ayn Rand Studies.

Today, I wanted to provide a link

to an interesting discussion that has been provoked by writer Anoop Verma, on

the blog, For the New Intellectual.

His discussion and many responses can also be found among those who have access

to Facebook. I've added an excerpt from his blog post, which is not a formal

review, but a few provocative thoughts about one particular aspect of the book

highlighting some of the parallels between Karl Marx and Ayn Rand: "Is

There a Connection Between Ayn Rand and Karl Marx?"

Readers can find

an excerpt from the blog post

here.

Also, check out my index of Russian Radical reviews

here, as

well as an index to all of the blog posts on "Russian Radical 2.0"

here.

Enjoy!

BLOG POST #12: RUSSIAN RADICAL 2.0: AYN RAND ON CONSERVATIVES AND LIBERALS (10 November 2016)

Anoop Verma, on his site "For the New Intellectual," has posted a thread dealing with those sections of Ayn Rand: The Russian Radical dealing with Ayn Rand's rejection of the conventional conservative-liberal polarity in American politics.

I just wanted to thank Anoop for bringing attention to this important issue on his site; those wishing to read his discussion should check it out here.

BLOG POST #13: RUSSIAN RADICAL 2.0: THE DIALECTICAL RAND (14 December 2017)

My essay, "Reply to Critics of Russian Radical 2.0: The Dialectical

Rand," which appears in the December 2017 issue of The

Journal of Ayn Rand Studies, has apparently caused a bit of a

stir on Facebook, as folks discuss one part of my essay---though it appears few

have actually read the essay in full.

Anoop Verma has already posted a piece on his Verma Report: Ayn

Rand: The Philosopher Who Came In From the Soviet Union, a clever

play on Le Carre's The Spy Who Came in From the Cold.

I am reluctant to say much about the essay until people have actually read it,

though in truth, I think the essay speaks for itself. I did, however, clarify

one issue that has dogged my use of the word "dialectics" for over twenty years

now. Some folks may think my use of the word is idiosyncratic, but as I explain

in the first four chapters of my book, Total

Freedom: Toward a Dialectical Libertarianism, though the word has

come to be associated with various untenable philosophical doctrines, it

originates among the ancients, and its theoretical father is Aristotle. On

Facebook, I posted this reply to one commentator:

I absolutely do not identify dialectics as the Hegelian "triad" of

thesis-antithesis-synthesis (though this is more a formulation of Fichte, rather

than Hegel); I identify it as the art of context-keeping. It is this art that

led even Peikoff to exclaim that Hegel was "right" methodologically when he said

"The True is the Whole"--but very wrong in terms of his philosophical premises.

The original theoretician of "dialectics" was Aristotle, whom even Hegel called

"The Fountainhead" (and he used those specific words) of dialectical inquiry:

that is, Hegel saw Aristotle as the father of a mode of analysis that sought to

understand any problem from multiple vantage points, on different levels of

generality, and across time, so as to get a more enriched perspective of the

fuller context of the problem, and how it is often an expression of a larger

system of interconnected problems.

It would really be great if folks would actually read my book, and the new JARS

article before hoisting onto me theories that I explicitly reject. (I address

the issue of false alternatives in the book and in the newest essay as well.)

I agree completely about defining one's terms, . . . and I've devoted a trilogy

of books (Marx, Hayek, and Utopia, Ayn Rand: The Russian Radical,

and Total Freedom: Toward a Dialectical Libertarianism) to explaining exactly what

I mean by dialectics. In the concluding book of the trilogy, in fact, I

reconstruct the entire history of the concept in the first three chapters, and

then devote a full chapter to defining dialectics, and unpacking that definition

in such a way that it cannot possibly be confused with any of the ways in which

it has been distorted. And boy has it been distorted..

Stay tuned; there may be a few additional exchanges I'll post here.

Postscript (15

December 2017): In a tangential Facebook discussion on Marxism, I had the

opportunity to pay tribute to a brilliant friend and colleague, the late Don

Lavoie:

Just a note on Don Lavoie: He was a wonderful friend and a magnificent

colleague; he was among the most supportive people in terms of his encouragement

of my own intellectual adventure. And it's no coincidence that we both did our

dissertations at NYU with Marxists and Austrians on our dissertation committees.

He was certainly among the most well-read libertarians on Marxism (as is Pete

Boettke), and in fact, when I was the President of the NYU chapter of Students

for a Libertarian Society, we sponsored a debate between Don and Bertell Ollman.

It was terrific---as Don was a kind of Hayekian anarchist and Bertell remains

one of the finest Marxist scholars of his generation.

I also spoke of a Marxism discussion list that I cofounded:

I have fond memories of interacting with Doug Henwood, Jim Farmelant, and others

on the Marxism discussion list that I cofounded, and that is still operating

("Marxism-Thaxis", as in "THeory" and "prAXIS"---yes, I proposed that crazy

mashup for the list name). . . . [C]halk it up to my years as a mobile college

DJ, always looking for a way to create "mashups" of different styles of music

that kept the crowd dancing... [Additionally], I can tell you one thing: While I

took more than my share of lumps on marxism-thaxis over discussions on

everything from the calculation debate to dialectics and Ayn Rand, I honestly do

not believe I was ever treated with the level of vicious disrespect that I have

experienced over the last 20+ years in certain "Objectivist" circles. The Thaxis

folks may have thought me eccentric and crazy, but most participants treated me

with respect. Maybe some of it had to do with the fact that Bertell Ollman was

providing provocative blurbs for my books, but I think a lot of it had to do

with the fact that even though I had my disagreements with Marxism, I had

devoted much time to studying and understanding the Marxist tradition, rather

than engaging in sweeping, uninformed denunciations.

Postscript (18

December 2017): Anoop Verma's blog post on my essay has elicited a provocative

response from Irfan Khawaja, which can be viewed here.

Irfan says:

It's an understatement to say that Sciabarra's thesis was harshly criticized by

orthodox Objectivists associated with ARI; Sciabarra himself was marked out for

personal attack, and attempts were made to destroy his reputation and career. I

taught for several years (1997-98, and 1999-2005) at The College of New Jersey

with the late Allan Gotthelf, a well-known Objectivist philosopher associated

with ARI. Allan told me explicitly that the point of his polemics against

Sciabarra's book was to discredit Sciabarra as a scholar, to wreck his

reputation, to wreck his career, and to make sure that no reputable scholar were

ever to take him seriously. He set out, deliberately and explicitly, to make

Sciabarra's views appear absurd, and to make Sciabarra himself to appear a

laughing-stock. People around Allan regularly referred to Sciabarra with

derision, and encouraged others to do so. They trashed JARS as an enterprise,

and encouraged others to do so. One had to be there to bear witness to the

intensity of the animosity felt, not just for Sciabarra's ideas, but for

Sciabarra himself. I was there. It was an unpleasantly memorable experience.

The irony is that though Chris and I are friends, I've never been convinced that

Ayn Rand was a dialectical thinker. Chris's work had an oddly mirror-image

effect on me. Instead of concluding that Rand was a dialectical thinker, I spent

some time with Aristotle's Topics, and came to the conclusion that the

problem with Rand was that she wasn't a dialectical thinker. (Indeed, the

problem with a lot of contemporary philosophy is that dialectics has fallen

through the cracks.) Or to the extent that Rand was a dialectical thinker, the

dialectical tendencies in her work were at odds with what she took herself,

self-consciously, to be doing.

In any case, though it'd be pretentious to call myself a "dialectical thinker,"

I'm now more strongly influenced by dialectics than I once was. I owe that to

Chris. So while I don't literally accept the truth of his thesis, I've ended up

being positively influenced by it all the same. Despite the efforts made to shut

him up and discredit him, his work found an audience, and made a lasting

impression. That's quite a vindication, and a well-deserved one.

Not only did Gotthelf try to undermine Chris's reputation and career, he did his

best to de-legitimize JARS as an enterprise. He (Gotthelf) had a position on the

editorial board of The Philosopher's Index (a major indexing service) and did

his best to get JARS excluded from their indexing service, so as to minimize its

exposure to the profession. My ex-wife Carrie-Ann Biondi was (and I think is) an

indexer TPI, and she told me that she had no idea that Gotthelf had engaged in

such efforts. So the efforts were made, but they were made covertly.

But if you knew where Gotthelf stood--and he hardly made it a secret--none of

this came as a surprise. The whole episode has been covered up and rationalized

by appealing to Gotthelf's undeniably distinguished career as an Aristotle

scholar. What has gone unremarked is the fact that Gotthelf self-consciously

used his credentials to get away with malfeasances that he knew he could get

away with precisely because he had those credentials.

The pattern is part of the Objectivist obsession with Great Men and Their

Achievements: a Great Achiever is permitted to do what and as he likes without

having to live up to the pedestrian ethical standards that apply to

non-achievers, the lowly proletariat of the Objectivist ethical universe. Never

mind the fact that no one has yet managed to define precisely what counts as

"productive work" on the Objectivist account. "Intuitively," everybody "knows"

what counts and what doesn't. Definitions are only the guardians of rationality

until you put them to sleep.

And on 19 December 2017, Irfan continued:

I don't think we need to go very far in hunting down Gotthelf's motivation. The

motivation was transparent: Gotthelf had very fixed ideas about what Rand was

saying, and what scholarship on Rand should say and look like. Sciabarra's work

fit neither of his pre-conceptions, and neither did JARS.

But by the late 1990s and early 2000s, both "Russian Radical" and JARS had

started gaining currency in the scholarly community. This happened at a time

when ARI had decided, after a long hiatus, to re-invest in the scholarly

enterprise. Simultaneously, David Kelley's organization, long regarded as a

bastion of openness and scholarly seriousness, began to take a populist turn,

and then, to fade from view. Gotthelf was well-acquainted with all of these

facts. From his perspective, if Sciabarra/JARS could be swept from the field,

ARI would have a monopoly on Rand scholarship. And a monopoly is what they had

wanted all along--as any reader of "Fact and Value" could figure out. The

important thing was to give this monopoly a moral/intellectual blessing so that

they could tell themselves and the world that they had earned it.

I don't think Allan was precisely "jealous" of Chris; he had so little respect

for Chris that jealousy couldn't have arisen. But he resented the attention that

Chris and JARS had gotten, attention that he regarded as undeserved, and that

ought to have been directed toward ARI and Anthem.

Roderick Long added a comment with regard to Gotthelf's scholarship and

behavior:

Certainly Gotthelf did some good scholarly work -- his work on Aristotle's

biology, for example, is first rate. Being capable of good scholarship and being

capable of unprofessional behaviour are, sadly, quite compatible.

BLOG POST #14: RUSSIAN RADICAL 2.0: A WALK DOWN MEMORY LANE (12 January 2018)

Anoop Verma took me for a walk down memory lane with his newest blog entry, "On

Ridpath's 'The Academic Deconstruction of Ayn Rand'." He also posted the

link to Facebook, which has, of course, led to a spirited exchange. I added this

comment about the publication history of my book, Ayn

Rand: The Russian Radical:

While you [Anoop] know I always appreciate you bringing attention to my work

(and even its critics; after all, I put excerpts from all reviews, positive and

negative, of all my work, right on my website), this is, of course, ancient

history. Check out the Ridpath material (including my replies) indexed here.

[Here are the direct links to an excerpt from the Ridpath

review and these two comments by

me.]

I do recall an interview that Ridpath gave some time after that essay appeared

and he made a comment that ARI-affiliated scholars were working for years on

Rand, and out of nowhere, this Sciabarra fellow came along and published this

atrocious volume that has gotten all this attention. It's like I was a

party-crasher. But believe me, the last thing any scholar would do, certainly

back in 1995, would be to pick Ayn Rand as a subject for scholarly inquiry, and

make her the focus of a 500-page book. Not exactly a way of endearing oneself to

the predominantly left-wing academy or those conservative professors who opposed

the lefties, and Ayn Rand as well.

As it happened, the book was rejected by many publishers before it found its

home at Pennsylvania State University Press. Most university presses that

reviewed the manuscript showed an appreciation of its scholarly quality, but

rejected it because the subject (Rand) was "not worthy of scholarly attention."

And they were quite honest about this. And virtually all trade presses showed an

appreciation of any book on Rand that could potentially spike commercial sales,

except they rejected the book because it was too scholarly.

So it was to the credit of Penn State Press, and its then director, Sandy

Thatcher, that the book was published---going through seven printings before

being republished in a second expanded edition in 2013. My relationship with

PSUP

also expanded, as they published the volume I coedited with Mimi Gladstein, Feminist

Interpretations of Ayn Rand,

as well as the third installment of my "Dialectics and Liberty Trilogy": Total

Freedom: Toward a Dialectical Libertarianism.

In 2013, they also became the publishers of a journal that I was a founding

coeditor of back in 1999: The

Journal of Ayn Rand Studies. So the work continues...

BLOG POST #15: THE NEW JOURNAL OF AYN RAND STUDIES WEBSITE (10 June 2019)

In a Notablog post with regard to the new JARS website, a Facebook attack on JARS and on my work was met with the following response by me:

But in the meanwhile, I'm violating my own principles here; all I did was post something with regard to a proud accomplishment, a new site and a forthcoming blockbuster issue of The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies. And what I've seen in return for this announcement is beyond appalling. Some people in this world should be ashamed of themselves, but I'm not going to litigate a personal matter on a public board. Been there, but will never allow myself to join in on the Sciabarra F---fest. It's getting so old, except for the fact that new people keep busting blood vessels over my very existence. Sorry to disappoint: I'm not dead yet.

|

|

|