NOTABLOG

MONTHLY ARCHIVES: 2002 - 2020

| APRIL 2020 | JUNE 2020 |

"Music is God": Alice Herz-Sommer, Beethoven, and the Power of Music

For those who have never heard of Alice

Herz-Sommer (26 November 1903-23 February 2014), she was a

Prague-born Jewish pianist who survived Theresienstadt

concentration camp (the conditions of which were starkly dramatized

in the grand miniseries "War

and Remembrance," 1988-1989).

She died at the age of 110, one of the world's oldest known Holocaust survivors,

one year after having been featured in the 2013 Academy Award-winning "Best

Short Documentary" film: "The

Lady in Number 6: Music Saved My Life."

For a glimpse of that film, check out the

clip on YouTube (the full film is available here),

which ends with several glorious quotes from figures as varied as Plato ("Music

is a moral law. It gives soul to the universe, wings to the mind, flight to the

imagination, and charm and gaiety to life and to everything") and Ludwig

van Beethoven ("Music is a higher revelation than all wisdom and

philosophy").

On 17 December 2020, we will mark the

250th anniversary of the great German composer's birth. He was one

of Alice's

personal heroes. She once said: "Music

saved my life and music saves me still ... I am Jewish, but Beethoven is my

religion."

Posted by chris at 04:13 PM | Permalink |

Posted to Film

/ TV / Theater Review | Music | Politics

(Theory, History, Now)

Coronavirus (26): Gallows Humor In These Times

So I was watching the Daily Cuomo Coronavirus Press Conference, and on hand were

comic personalities who have lived in Brooklyn: Chris

Rock and Rosie

Perez. And toward the end of the conference, Chris Rock cracked a

joke that made me chuckle, in the grand tradition of Brooklyn Gallows Humor

(remember Marisa

Tomei playing Brooklynite Mona

Lisa Vito in the 1992 film, "My

Cousin Vinny" saying "'Cause

he's dead" [Yarn link]?).

Here's the clip from the conference [YouTube link].

Well, not everybody thought it was funny. The clip was posted to YouTube by "The

Red Right and You" who complained:

Emperor Cuomo introduced Chris Rock and Rosie Perez as his new spokespeople to

communicate the importance of social distancing in New York. Towards the end of

the press conference Cuomo was talking about the spring breaker who said he

wasn't going to let the virus stop him from partying. Chris then said "now he's

dead" and Cuomo gave a great big belly laugh. Will he apologize? Just imagine if

that was Trump and what the media would be saying about him joking about someone

dying from the virus.

To which I replied:

Where is your sense of humor? I didn't vote for either Cuomo or Trump, but I

chuckled over this, the way I regularly chuckle over things that come out of

Trump's mouth. Chris Rock is hilarious... and for New Yorkers, like me, who have

had neighbors dying to the left and dying to the right, this was the kind of

gallows humor that has emerged in these times. Gimme a break!

Sheesh.

Posted by chris at 02:37 PM | Permalink |

Posted to Film

/ TV / Theater Review | Frivolity | Politics

(Theory, History, Now)

The Dialectics of Liberty: Camplin Colloquy Published on Medium.com

Medium.com has

just published an edited version of a colloquy that was featured on The

Dialectics of Liberty Study Group, devoted to the systematic

discussion of the essays in The Dialectics of Liberty: Exploring the Context

of Human Freedom, co-edited by Roger Bissell, Chris Matthew Sciabarra, and

Ed Younkins.

Chapter 18, "Aesthetics,

Ritual, Property, and Fish: A Dialectical Approach to the Evolutionary

Foundations of Property," by Troy Camplin, was the subject of

discussion from March 29th through April 4th.

It has now been published as a self-contained piece on the Medium.com site and

can be viewed here.

The inclusion of Camplin's essay in this trailblazing anthology is yet one more

illustration of the book's wide scope and Big Tent approach to the

dialectical-libertarian research project.

Much more exciting news about the book, forthcoming reviews, and symposia to

come... stay tuned!

Posted by chris at 05:33 PM | Permalink |

Posted to Austrian

Economics | Dialectics | Pedagogy | Rand

Studies | Religion | Sexuality

The Dialectics of Liberty: McCloskey Colloquy Published in Poroi

Poroi: An Interdisciplinary Journal of

Rhetorical Analysis and Invention has

just published "Rhetoric,

Dialectic, and Dogmatism: A Colloquy on Deirdre Nansen McCloskey's 'Free Speech,

Rhetoric, and a Free Economy'" [pdf link] in its May 2020 issue (vol.

45, no. 2), as part of its 45th anniversary edition. This is the final, edited

version of the discussion that emerged from the Dialectics of Liberty Facebook

Study Group.

Thanks to all of our participants, who are credited in the article, and to

Deirdre McCloskey for facilitating the publication of this colloquy, extending

the reach of The

Dialectics of Liberty: Exploring the Context of Human Freedom,

the anthology I co-edited with Roger Bissell and Ed Younkins.

Posted by chris at 06:00 PM | Permalink |

Posted to Dialectics | Periodicals

Song of the Day #1788

Song of the Day: Stuck

with U features the words and music of a host

of writers, including the two who duet on this tune: Ariana

Grande and Justin

Bieber. The song debuts at #1

on the Billboard Hot 100 singles chart this week. It's got a

retro doo-wop feel, and an

adorable video that is a sign of the times [YouTube link]. All the proceeds

from the song are being donated to the First

Responders Children's Foundation.

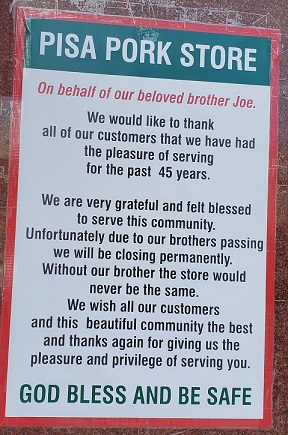

Coronavirus (25): Joseph "Joe Pisa" Sanfratello, RIP

On May 12, 2020, our neighborhood lost the proprietor of Pisa Pork Store on West

6th Street and Kings Highway in Brooklyn, New York, a block or so from our home.

He was Joseph

"Joe Pisa" Sanfratello, a "legend" to all those who knew of the

wonderful store he helped create and sustain all these years to serve loyal

customers who came from near and far because they were grateful for the A+

quality of the foods he sold and the A+++ hospitality of Joe, his family, and

his workers.

Where else could you get a piece of fresh mozzarella or a rice ball---handed to

you by Joe himself---while you waited on line to finally put in your order?

You'd go into that store figuring you'd purchase a few items, only to walk out

with bagfuls of Italian delicacies, cold cuts, and homemade meals prepared with

love.

Joe was one more casualty in our Brooklyn neighborhood from COVID-19. Today,

there will be a private family visitation at Cusimano and Russo Funeral Home and

a committal service at Saint John Cemetery in Middle Village, New York. We wrote

in his online memory book:

Our hearts are broken to read of the passing of Joe. Our deepest condolences to

all his family and friends; we will miss him very much. Our neighborhood and

community are greatly diminished without him.

Love always,

The Sciabarra Famly

Outside Pisa Pork Store, a makeshift memorial has formed; the sign outside the

store promises that they'll be back before too long. And I might add: So will

all of New York!

RIP, Joe.

Posted by chris at 12:41 AM | Permalink |

Posted to Culture | Politics

(Theory, History, Now) | Remembrance

Song of the Day #1787

Song of the Day: Elegy

for Barbara [YouTube link], composed by Roger

E. Bissell, was written in memory of writer and lecturer Barbara

Branden. Today is the 91st

anniversary of Barbara's birth [YouTube link]. Having passed

away on 11 December 2013, she left behind a

wonderful personal and intellectual legacy. I was proud to have

written the Foreword to her posthumously published book, Think

as If Your Life Depends On It: Principles of Efficient Thinking and Other

Lectures. You remain deep in my heart, dear

friend.

Posted by chris at 12:01 AM | Permalink |

Posted to Music | Rand

Studies | Remembrance

Coronavirus (24): Three Cheers for the Ol' Folks

Having previously addressed one of the more absurd episodes during this

Corona-Crisis with regard to calls for old folks to

sacrifice themselves for the common good, I was happy to read three

human interest stories that I found uplifting in the extreme.

Submitted for your approval:

the case of one Maria

Rodriguez, 87 years old:

When Brooklyn great-grandmother Maria

Rodriguez realized she was losing her fight with coronavirus at home,

she braced herself for the worst. She checked into NYU Langone Hospital-Brooklyn

on Monday. And then she told her daughter, Norma Collado, to be strong and to be

patient if she couldn't be buried right away. She asked that her great

grandchildren be taken to the cemetery to see her off when the time came. And

she put fresh nail polish on her fingernails so the mortician wouldn't have to.

"The color was purple, like a lilac," Collado said. But as it turned out, the

87-year-old Rodriguez was stronger than the coronavirus that put her in the

hospital. Rodriguez, of Borough Park, is now recovering at her daughter's home

in Perth Amboy. Three days after she entered the hospital---eight days after she

first fell ill---Rodriguez became the 850th patient who tested positive with

coronavirus to be discharged from NYU Langone Hospital-Brooklyn.

I'm all the more happy to hear about how well NYU Langone is handling this

situation; I was due to have a lithotripsy there in mid-March, for a stone that

has taken up residence in my left kidney since the summer of 2018. Right now,

"elective" surgeries are still not available in NYC. But even if they were, as

long as my stone continues to defy the laws of gravity, I'm electing to stay as

far away from any medical facility in this city for as long as I can. Yes,

hospitalizations and intubations are down in the state and in the city, and for

two straight days, we have had death toll tallies of under 200 per day. Given a

plateau of nearly 800 deaths per day... there is cause for some optimism.

With the gradual improvement of the situation here in the Big Apple, there was

another news item in the New York Daily News that was just as nice to

read. Score another one for the Ol' Folks.

Submitted for your approval: the case of Tony

Vaccaro, 97 years old, famous

war photographer:

Tony Vaccaro's mother died in childbirth, and at a tender age he also lost his

father to tuberculosis. By age 5 he was ... orphaned in Italy, enduring beatings

from an uncle. As an American GI during World War II he survived the Battle of

Normandy. Now, a celebrated wartime and celebrity photographer at age 97, he is

getting over a bout with COVID-19. He attributes his longevity to "blind luck,

red wine" and determination. ... Vaccaro lives in Queens, a New York City

borough ravaged by the novel coronavirus, next to his son Frank, his twin

grandsons and his daughter-in-law Maria, who manages his archive of 500,000

photographs. He might have caught the virus in April from his son or while

walking in their neighbourhood, his daughter-in-law said. He was in the hospital

for only two days with mild symptoms and spent another week recovering. Then he

surprised everyone by getting up and shaving. "That was it," she said. "He's

walking around like nothing happened."

Since this virus has ravaged the elderly, news about an 87-year old great

grandmother and a 97-year old celebrated photographer beating the virus is an

inspiration. But they're practically kids next to this next victor!

Submitted for your approval: Frances

Abbraciamento, who turned 107 on May 9th:

Centenarian Frances Abbracciamento of Queens had caught a cold in late March

during the peak of the coronavirus pandemic in New York. Days later the

106-year-old was diagnosed with pneumonia, and her four children prepared for

the worst. "We really thought we were going to lose her," her daughter, Alda

Spina, told the Daily News. But by the end of April, Abbracciamento ...

had made a near-full recovery---and it was only then that her family learned she

had survived coronavirus. "We couldn't believe it," said Spina, who received her

mom's COVID-19 test results on April 21. "I never thought in a million years she

would survive it. People don't survive it."

I am reminded of that 1962

third season "Twilight

Zone" episode, "Kick

the Can," wherein Rod Serling reminds us, in his closing narration

"that childhood, maturity, and old age are curiously intertwined and not

separate."

Three cheers to these three ol' folks for having "kicked the can" down the

road... and survived their respective bouts with COVID-19. Here's to kicking the

can down the road for the thousands of others affected by this pandemic.

Posted by chris at 02:02 PM | Permalink |

Posted to Culture | Film

/ TV / Theater Review | Politics

(Theory, History, Now)

Coronavirus (23): Mutual Aid During a Pandemic (or Three Cheers for the

Volunteers!)

There is a really wonderful, thought-provoking article in New Yorker magazine:

"What

Mutual Aid Can Do During a Pandemic: A Radical Practice is Suddenly Getting

Mainstream Attention. Will it Change How We Help One Another?" by Jia

Tolentino. It heralds the greatness of the "Invisible Hand" that guides mutual

aid among caring, human beings, in the midst of a pandemic.

Here are a few takeaway points from the article---a rather extraordinary piece

to be found in such a mainstream magazine. Of special attention to

freedom-lovers is its citing of journalist Rose

Wilder Lane, whose book, The

Discovery of Freedom, was published in the same year as Isabel

Paterson's The

God of the Machine and Ayn

Rand's novel, The

Fountainhead.

In the midst of World War II, these

three women, whose books were all published in 1943, heralded the

birth of the modern libertarian movement. From the Tolentino article:

We are not accustomed to destruction looking, at first, like emptiness. The

coronavirus pandemic is disorienting in part because it defies our normal

cause-and-effect shortcuts to understanding the world. The source of danger is

invisible; the most effective solution involves willing paralysis; we won't know

the consequences of today's actions until two weeks have passed. Everything

circles a bewildering paradox: other people are both a threat and a lifeline.

Physical connection could kill us, but civic connection is the only way to

survive.

In March, even before widespread workplace closures and self-isolation, people

throughout the country began establishing informal networks to meet the new

needs of those around them. In Aurora, Colorado, a group of librarians started

assembling kits of essentials for the elderly and for children who wouldn't be

getting their usual meals at school. Disabled people in the Bay Area organized

assistance for one another; a large collective in Seattle set out explicitly to

help "Undocumented, LGBTQI, Black, Indigenous, People of Color, Elderly, and

Disabled, folxs who are bearing the brunt of this social crisis." Undergrads

helped other undergrads who had been barred from dorms and cut off from meal

plans. Prison abolitionists raised money so that incarcerated people could

purchase commissary soap. And, in New York City, dozens of groups across all

five boroughs signed up volunteers to provide child care and pet care, deliver

medicine and groceries, and raise money for food and rent. Relief funds were

organized for movie-theatre employees, sex workers, and street venders. Shortly

before the city's restaurants closed, on March 16th, leaving nearly a quarter of

a million people out of work, three restaurant employees started the Service

Workers Coalition, quickly raising more than twenty-five thousand dollars to

distribute as weekly stipends. Similar groups, some of which were organized by

restaurant owners, are now active nationwide.

As the press reported on this immediate outpouring of self-organized

voluntarism, the term applied to these efforts, again and again, was "mutual

aid," which has entered the lexicon of the coronavirus era alongside "social

distancing" and "flatten the curve." It's not a new term, or a new idea, but it

has generally existed outside the mainstream. Informal child-care collectives,

transgender support groups, and other ad-hoc organizations operate without the

top-down leadership or philanthropic funding that most charities depend on.

There is no comprehensive directory of such groups, most of which do not seek or

receive much attention. But, suddenly, they seemed to be everywhere.

On March 17th, I signed up for a new mutual-aid network in my neighborhood, in

Brooklyn, and used a platform called Leveler to make micropayments to

out-of-work freelancers. Then I trekked to the thirty-five-thousand-square-foot

Fairway in Harlem to meet Liam Elkind, a founder of Invisible Hands, which was

providing free grocery delivery to the elderly, the ill, and the

immunocompromised in New York. Elkind, a junior at Yale, had been at his

family's place, in Morningside Heights, for spring break when the crisis began.

Working with his friends Simone Policano, an artist, and Healy Chait, a business

major at N.Y.U., he built the group's sleek Web site in a day. During the next

ninety-six hours, twelve hundred people volunteered; some of them helped to

translate the organization's flyer into more than a dozen languages and

distributed copies of it to buildings around the city. By the time I met him,

Elkind and his co-founders had spoken to people hoping to create Invisible Hands

chapters in San Francisco, Los Angeles, Boston, and Chicago. The group was

featured on "Fox & Friends," in a segment about young people stepping up in the

pandemic; the co-host Brian Kilmeade encouraged viewers to send in more

"inspirational stories and photos of people doing great things." ...

Radicalism has been at the heart of mutual aid since it was introduced as a

political idea. In 1902, the Russian naturalist and anarcho-communist Peter

Kropotkin---who was born a prince in 1842, got sent to prison in his early

thirties for belonging to a banned intellectual society, and spent the next

forty years as a writer in Europe---published the book Mutual Aid: A Factor

of Evolution. Kropotkin identifies solidarity as an essential practice in

the lives of swallows and marmots and primitive hunter-gatherers; cooperation,

he argues, was what allowed people in medieval villages and nineteenth-century

farming syndicates to survive. That inborn solidarity has been undermined, in

his view, by the principle of private property and the work of state

institutions. Even so, he maintains, mutual aid is "the necessary foundation of

everyday life" in downtrodden communities, and "the best guarantee of a still

loftier evolution of our race."

Charitable organizations are typically governed hierarchically, with decisions

informed by donors and board members. Mutual-aid projects tend to be shaped by

volunteers and the recipients of services. Both mutual aid and charity address

the effects of inequality, but mutual aid is aimed at root causes---at the

structures that created inequality in the first place. ...

Historically, in the United States, mutual-aid networks have proliferated mostly

in communities that the state has chosen not to help. The peak of such

organizing may have come in the late sixties and early seventies, when Street

Transvestite Action Revolutionaries opened a shelter for homeless trans youth,

in New York, and the Black Panther Party started a free-breakfast program, which

within its first year was feeding twenty thousand children in nineteen cities

across the country. J. Edgar Hoover worried that the program would threaten

"efforts by authorities to neutralize the BPP and destroy what it stands for"; a

few years later, the federal government formalized its own breakfast program for

public schools.

Crises can intensify the antagonism between the government and mutual-aid

workers. Dozens of cities restrict community efforts to feed the homeless; in

2019, activists with No More Deaths, a group that leaves water and supplies in

border-crossing corridors, were tried on federal charges, including driving in a

wilderness area and "abandoning property." But disasters can also force

otherwise opposing sides to work together. During Hurricane Sandy, the National

Guard, in the face of government failure, relied on the help of an Occupy Wall

Street offshoot, Occupy Sandy, to distribute supplies.

"Anarchists are not absolutist," Spade, the lawyer and activist, told me. "We

can believe in a diversity of tactics." ... The day-to-day practice of mutual

aid is simpler. It is a matter, she said, of "prefiguring the world in which you

want to live." ... In her book Good Neighbors: The Democracy of Everyday Life

in America, the Harvard political scientist Nancy L. Rosenblum considers the

American fondness for acts of neighborly aid and cooperation, both in ordinary

times, as with the pioneer practice of barn raising, and in periods of crisis.

In Rosenblum's view, "there is little evidence that disaster generates an

appetite for permanent, energetic civic engagement." On the contrary, "when

government and politics disappear from view as they do, we are left with the

not-so-innocuous fantasy of ungoverned reciprocity as the best and fully

adequate society." She cites the daughter of Laura Ingalls Wilder, Rose Wilder

Lane, who helped her mother craft classic narratives of neighborly kindness and

became a libertarian who opposed the New Deal and viewed Social Security as a

Ponzi scheme. ...

All the organizers I spoke to expressed a version of the hope that, after we

emerge from isolation, much more will seem possible, that we will expect more of

ourselves and of one another, that we will be permanently struck by the way our

actions depend on and affect people we may never see or know.

Whether or not you like the politics of some of the folks cited, the whole

article is worthy of your attention.

And three cheers for the volunteers.

Posted by chris at 11:37 AM | Permalink |

Posted to Culture | Politics

(Theory, History, Now) | Rand

Studies | Sexuality

Song of the Day #1786

Song of the Day: Mother features

the words and music of Billy

Walsh, Ryan

Tedder, Louis

Bell, Andrew

Watt, and Charlie

Puth, who released

this song in September 2019 [YouTube link]. Check out the video

single [YouTube link], with its

shuffle beat, and then check out a host of remixes by Fedde

Le Grand, Codeko, CPEN and Meridian [YouTube

links]. This song has absolutely nothing to do with Mother's

Day, but it gives me an opportunity to say Happy

Mother's Day to all the mothers out there!

Posted by chris at 12:20 AM | Permalink |

Posted to Music | Remembrance

Song of the Day #1785

Song of the Day: Tutti

Fruiti features the words

and music of Dorothy

LaBostrie and Little

Richard (aka Richard

Wayne Penniman), who died

today at the age of 87. His flamboyant, charismatic showmanship

combined the

"sacred" shouts of gospel the "profane" sounds of the blues. He would

be dubbed "The

Innovator, The Originator, and the Architect of Rock and Roll." His influence

on American popular music has been felt

across musical genres from rhythm

and blues to rock, soul, funk,

and hip

hop. A Rock

and Roll Hall of Famer, Little

Richard opened this signature song with that classic cry of "A-wop-bop-a-loo-bop-a-wop-bam-bom"---practically

announcing, in 1955, that a new era had arrived. Ranked as #1 on Mojo's "Top

100 Records That Changed the World," the song was later included on

the artist's 1957 debut album, "Here's

Little Richard". Check out this rock

and roll classic [YouTube link]. RIP, Little

Richard.

Posted by chris at 03:17 PM | Permalink |

Posted to Culture | Music | Remembrance

Coronavirus (22): Spring Cleaning (Or Three Cheers for Sanitation Workers!)

In July 2019, I was still clearing up the last 50 boxes of over 250 boxes of

papers and other items that had been packed by a professional cleaning service

in the days after October

10, 2013---when a fire, which nearly consumed our apartment and took

our precious lives, was extinguished by the heroic efforts of the FDNY.

Yes, my sister and I grieved for all the treasures that we lost---gifts from our

parents that could never be replaced, and objects of great sentimental value.

But we count our blessings that we were alive to grieve those losses! I

also counted my blessings that, after six years of reorganizing my entire file

system, restructuring my entire library, I finally completed the task of going

through those 50 boxes last July. I generated over 25 bags of recyclable paper

each week for four straight weeks, and was in touch with the Sanitation

Department workers at the B11

Sanitation Garage, which services the neighborhoods in South Brooklyn

(Bath Beach, Bensonhurst, and my very own beloved Gravesend), to give them a

heads-up that they should expect a large haul from our address. Each week, I

came to expect the best service from these guys, who break their butts day-in,

day-out to keep our streets clean.

During this Coronavirus crisis in NYC, I haven't heard a single public official

give a shout out to the "essential

workers" of the Sanitation Department who face great personal risk

every day, picking up garbage from every neighborhood in the city. I had the

occasion to call BK11 last night, before they picked up our garbage in the wee

hours of Friday morning, and the supervisor was informed that they should expect

yet another large haul from our address. Indeed, we've been doing a little

spring cleaning.

As the worker on the phone told me: "Everybody is home and it seems that everybody is

doing spring cleaning at the same time! So I don't know how much we can handle,

but we'll do our best." He expressed frustration over the fact that his

coworkers were among the "unsung heroes" during this crisis in our city, and I

couldn't agree with him more. I told him that I'd be proud to give them a

shout-out on my blog, and he told me, "I don't do social media." I told him,

"Well, I do, and I will be happy to express my appreciation to you guys

for all the hard work you do." He chuckled, before hanging up, and said: "Well,

hold off on that buddy... let's see if they pick up your garbage. But I'll

inform the supervisor!"

When I awoke this morning, all of the recyclables and regular household garbage

had been picked up, and I just smiled.

So, this is not a post filled with statistics or political theorizing. It is a

simple expression of gratitude to the folks who continue to haul our trash away,

twice a week, during a time when cleanliness

is next to godliness.

Thanks guys!

Posted by chris at 11:52 PM | Permalink |

Posted to Culture | Politics

(Theory, History, Now)

I'm Alive!

If one more person asks me to please post a pic so that they can judge for

themselves whether I'm alive or not ... sheesh... well, here it is. Haircut

self-administered... throwing caution to the wind!

Of course, one of my FB pals wanted further proof... with the front page of

today's "New York Daily News". The headline "OLD-AGE HOME OF HORRORS" does not

refer to either me or my home, thankyouverymuch.

<

Posted by chris at 01:33 PM | Permalink |

Posted to Blog

/ Personal Business

Coronavirus (21): Lockdowns, Libertarians, and Liberation

[On Facebook, I posted the following introduction to this essay: This is the

twenty-first installment in my discussion of the Coronavirus and its

implications. It is as much a self-critique as it is a critique of other points

of view; it is also an examination of the fault lines I have witnessed over the

years that have torn at the soul of libertarian thinking. It started out as a

piece that aired my disgust with some of the attitudes I've encountered; it

ended as an appeal to human empathy.]

On February 16, 1967, NBC aired the twenty-second episode in Season

1 of "Star

Trek"; it was called "Space

Seed," known to Trekkies as

the episode that introduced the world to the character Khan

Noonien Singh, he who would come back with fury in the 1982 film, "Star

Trek II: The Wrath of Khan."

For those who aren't familiar with this episode, the Starship Enterprise

intercepts the SS Botany Bay, a spacecraft with 84 humans aboard, in suspended

animation. Only 72 of them survive, including Khan, all of them products of a

selective breeding program that led to the Eugenics Wars of the 1990s. Khan led

these genetic superhumans to conquer one third of the world, until they were

driven to abandon planet Earth.

Toward the beginning of the episode, when all the facts of the unfolding mystery

of Botany

Bay have not yet been made clear, there's an

interesting exchange between Captain

James T. Kirk (played by William

Shatner) and the ever-logical

Vulcan, Mr.

Spock (played by Leonard

Nimoy):

Kirk: So much for my theory. I'm still waiting to hear yours.

Spock: Even a theory requires some facts, Captain. So far, I have none.

Kirk: And that irritates you, Mr. Spock?

Spock: Irritation?

Kirk: Yeah.

Spock: I am not capable of that emotion.

Kirk: My apologies, Mr. Spock. You suspect some danger, then?

Spock: Insufficient facts always invite danger, Captain.

Kirk: Well, better get some facts.

I recently saw this episode after many years, and just shook my head, thinking

of how timely that advice is in the midst of the current coronavirus pandemic.

While I'm going to do my best to deal with "some facts," I am not a Vulcan. As a

human being, I am very much prone to feeling "irritation." This post is going to

express a lot of irritation. But it is a cathartic exercise, one that I hope

will go a long way toward healing some of the divisions I've seen among many

people who call themselves "libertarians." Rather than "disown" such an emotion,

I'm just going to get it off my chest. A wise psychologist once told me: "Don't

keep anything in! Give the other guy the ulcer!"

Well, I don't wish any ulcers on anybody, anymore than I wish that the "naysayers"

among us get coronavirus and die just to prove a point.

Since I started blogging explicitly about coronavirus (and this is the

twenty-first post on that subject, beginning with a March

14, 2020 entry), I have lost count of the number of times that I have

found myself irritated---or downright outraged---over the kinds of things

I have heard coming out of the mouths of self-described libertarians.

In this post, I am focused primarily on libertarian responses to the virus

because that is the community with which I've been associated for the bulk of my

professional and intellectual life, albeit advocating a "dialectical

libertarianism" that has always tried to push my colleagues and friends toward a

greater understanding of the larger context within which human freedom

flourishes---or dies. But this confession of my irritation with some folks is as

much a therapeutic exercise that I urge everyone to embrace, no matter where you

stand on the current debate. Better self-understanding goes hand-in-hand with a

better understanding of those with whom you disagree. It also tends to shed more

light than heat. And, Lord knows, we've had a lot of heat over these last two

months.

For the record, I'll just state the obvious: As a radical libertarian (or

radical liberal, in the classical sense), I am typically irritated with folks on

both the socialist left and the nationalist right who have never met a crisis

they would not use as a means of increasing government power in the spheres of

their respective interest for "the common good." But critique must begin at

home. And since I find so much discord in my libertarian home, I feel the need

for even greater self-examination. I won't allow irritation with others to cloud

my vision of their humanity or their very real concerns.

Pandemics as the Pretext for Advancing Statism

Nevertheless, as part of this therapeutic exercise, I wish to make explicit the

very first time I began to feel a level of irritation with some of my

libertarian colleagues. It came from those who first declared it a hoax or an

exaggeration, being used by those in power who sought to augment the power of

the state over our lives. To be generous, many of these folks come from a "good"

place; they are understandably concerned with the history of corrupt

entanglements that mark the state-science nexus, which has given us every

instrument of mass terror and every weapon of mass destruction in the modern

era. They see that with advancing government control over our society in the

name of an emergency, there comes a form of militarization that starts to infect

the body politic in ways that are just as insidious as the virus itself.

I am deeply aware of the importance of this issue. As I pointed out in my second

Notablog entry on the coronavirus, "Disease

and Dictatorship":

First, there is a need to put all this into a larger context with regard to the

policies of the Chinese government [which dealt with the first outbreak of the

virus in the city of Wuhan]. This is the same government that has maintained

concentration camps (euphemistically described as "re-education camps") for

nearly two million Muslims, while waging war on those seeking freedom from

Beijing's control over the people of Hong Kong. So the "Chinese model" continues

to be an authoritarian one, whether it is used to contain people or pandemics. I

don't know all the answers on how to confront a pandemic, but clearly the

draconian measures enacted by some of those in power will have an impact that

far outlasts the containment of any disease. Most governments have referred to

this as a war, but all wars have always been accompanied by a vast increase in

the role of the state in ways that never quite go-back to "pre-war" levels. This

isn't a call to anarchy (at least not yet...)---but it is a call to vigilance on

behalf of human liberty, even in the face of a dreaded disease.

Indeed, as my friend Pete

Boettke recently reminded us, it was in volume three of Law,

Legislation, and Liberty that F. A. Hayek warned:

"Emergencies" have always been the pretext on which the safeguards of individual

liberty have been eroded---and once they are suspended it is not difficult for

anyone who has assumed such emergency powers to see to it that the emergency

persists.

The Problem of Confirmation Bias

But there was something about the early response to the coronavirus as a "hoax"

or an "exaggeration" that was eerily familiar to me. Back in the 1980s, when

HIV/AIDS was killing off a generation of gay men in the West (while ravaging a

largely heterosexual population in Africa), some libertarians (including those

influenced by Ayn Rand), ever fearful of those who proposed a growing

governmental role in both medical research and in locking down bathhouses that

were transmission belts for promiscuous, unsafe sex, grabbed onto the work of

the molecular biologist Peter

Duesberg, who played a major role in what became known as the AIDS

denialism controversy. Duesberg was among those dissenting scientists

who argued that there was no connection between HIV and AIDS, and that gay men

were dying en masse because of recreational and pharmaceutical drug use, and

then, later, by the use of AZT, an early antiviral treatment to combat those

with symptoms of the disease.

If the scientific community had accepted Duesberg's theories, hundreds of

thousands of people would be dead today. The blood supply would never have been

secured, since HIV screening of blood donors would never have become public

policy, and countless thousands of people receiving blood transfusions would

have been infected by HIV and would have subsequently died from opportunistic

infections. A whole array of "cocktail" drugs were developed that have targeted

HIV, the virus that causes Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, and they have

been effective in keeping people alive, reducing their viral load down to

undetectable levels, boosting their T-cell counts, and allowing them to go on to

live normal, productive, and creative lives. Still, safe sex remains the mantra

of the day.

So, while many libertarians have been at the forefront of rolling back the

state's interference in people's personal lives, advocating the elimination of

discriminatory anti-sodomy and marriage laws, there were some libertarians who,

early on, in the AIDS epidemic, grabbed onto Duesberg's theories as scientific

proof that the whole HIV/AIDS thing was a pretext for the expansion of the

state-science nexus. Confirmation

bias is an especially strong urge for anyone with strong convictions.

All the more reason to constantly check one's premises, as Rand once urged.

My own libertarian approach has always had a dialectical hue---which

means that I try not to jump to conclusions with ideological blinders, without

first addressing the real conditions that exist, and placing them within

a larger context. No state can wipe the canvas clean; the historical

attempts to do so have left oceans of human blood in their wake.

And yet, each of us is part of the very canvas on which we wish to leave our

mark. This must be recognized especially by those of us who offer a political

vision for a noncoercive society free of oppression.

So I can't wipe my own canvas clean. Just as I remain a hard-core libertarian, I

am also a New Yorker to my core. And I've seen up close and personal the

death and destruction that this virus has caused to the people in my

state and in the city of my birth, the city where I will stay until the day I

die---because no terrorists, no viruses, will ever drive me away from the place

I call home. It is deeply saddening to see my hometown re-discovering, yet

again, what it means to be crowned "Ground

Zero."

When New York first earned the "Ground Zero" distinction, back on September 11,

2001, the ideological fissures in the libertarian movement were just as

apparent. Neoconservatives were leading the way, not merely to strike back at

those responsible for the terrorist attacks, but to begin a "nation-building"

crusade, with no regard for the cultural or historical context of the countries

impacted by their wrongheaded policies. What followed was a vast expansion of

the National Security State through the Patriot

Act (opposed by only three Republicans in the House of

Representatives), which continues to be used in ways unrelated to "Homeland

Security," further eroding civil liberties in this country. An unjustified war

in Iraq destabilized the entire region, leading to unintended consequences that

will be with us for generations to come.

At the time, I found myself at odds with many libertarians of a more

"Objectivist" bent who wanted to annihilate the Middle East with nuclear

weapons, unconcerned with the side effects of, say, a nuclear winter. Times were

tough for any libertarian, like myself, who argued

that 9/11 was primarily a blow-back event brought about by years of brutal US

intervention abroad, but who also condemned the mass murder of

thousands of innocent civilians by Osama Bin Laden and Al Qaeda in their

terrorist attacks on that tragic day. I supported targeted strikes against Al

Qaeda, while also arguing that the United States should get the hell out of the

Middle East and the rest of the world's hot spots. I was called a "traitor" by

many in Objectivist circles. It never phased these folks that Rand herself had

opposed US entrance into World War II, and actively opposed US wars in Korea and

Vietnam, the latter, while troops were on the ground, even counseling

draftees to get good attorneys, because she was also opposed to military

conscription. Unlike

her progeny, she saw that there was a highly toxic, organic

relationship between domestic interventionism at home and "pull-peddling"

interventionism abroad.

Ironically, one of those Objectivists who favored the war in Iraq was Robert

Tracinski. Today, I find myself in greater agreement with Tracinski,

especially in a recent, wide-ranging

essay, which dissects the arguments of those who downplay the impact

of COVID-19, people like Richard Epstein, Michael Fumento, Tucker Carlson, Britt

Hume, Glenn Beck, Texas Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick (whom I excoriated here)

and various Objectivists. Tracinski criticizes those who argue that

"there are no libertarians in a pandemic," the idea that the coronavirus

response proves how much we need Big Government. ... But there has also been an

attempt to portray the pandemic as an overblown hysteria, a hoax designed to

impose dictatorship on us in the form of mandatory social isolation. The

unstated premise is that if the pandemic were real, it actually would make the

case for Big Government, so therefore it cannot be admitted to be a genuine

threat. ... The basic facts are that this virus spreads more quickly and easily

than the flu and is about ten times more deadly, with a mortality rate in the

neighborhood of one to two percent. ... This is not the Black Death or Ebola,

diseases with mortality rates of about 50%, and I have no doubt there are eras

in history when a mortality rate of 2% would barely have been noticed. But we

are very fortunate not to live in one of those eras. Given our high standards of

medical care and low death rates from other causes, COVID-19 produces dramatic

increases in mortality to levels far above the norm. And just in terms of

absolute numbers, a morality rate of one to two percent means that its unchecked

spread would be likely to produce a death toll in the millions in the US alone,

in the span of just a year. By comparison, a little over 400,000 Americans died

in all of World War II. I don't know by what standard a potential death toll

greater than that of a major war would not be considered a catastrophe. ... The

point is that this is not "fake news" coming from the left-wing media. It is

really happening, and people we know are trying to tell us about it.

Facing Facts

In the face of growing

evidence, it does seem that the "hoax" theory has ebbed in most

libertarian circles. But there are still those who hang onto the belief that

this whole "pandemic" (in scare quotes) is overblown and nothing to worry about,

except for those older folks with pre-existing conditions (like me, for

example), who are going to die at some point anyway (aren't we all?). It's the

kind of stance that leads people to view libertarians as not having a single

empathetic bone in their crippled bodies.

And some of these folks have claimed further that the New York statistics in

particular are being artificially "inflated" to prolong the current lockdown. I

addressed that issue directly in

this post, and I have yet to receive a satisfactory response to it.

While it may take years to truly understand the full story of this virus, in the

end, I must begin with the evidence of my own senses. As I related in that

"Reality Check" post cited above, it was on the last day of February that I sat

in an Emergency Room at Mount

Sinai Brooklyn, dealing with some complications from a

lifelong medical condition, and could not believe the growing volume

of patients being ushered in for immediate care. The EMTs, doctors, and nurses,

all expressed astonishment over the number of people who were reporting upper

respiratory distress. The warning signs for COVID-19 precautions were plastered

all over the ER that night; it was only a preamble to all that was to come. As

it turned out, this was the day before the very first reported death in New York

state attributed to COVID-19. Since that date, Mount

Sinai Brooklyn has been overwhelmed.

I have spoken to scores of doctors, nurses, EMTs, and first responders, and

neighbors from all over the tri-state area. The horror stories I'm being told by

people I trust implicitly make the statistics pale by comparison. The

bodies are piling up faster than the hospital morgues or the funeral homes can

handle. In the Flatlands section of Brooklyn, not far from my

neighborhood, friends of mine have complained about the odor of decomposing

bodies being stored in U-Haul trucks outside the Andrew Cleckley Funeral Home on

Utica Avenue. The news has reported that between "30 to 60 bodies were being

stored in two U-Haul trucks outside the funeral home" in "unsanitary and

undignified" conditions. This is the reality in New York.

But anecdotal evidence does not take the place of raw statistics. So let's

discuss those statistics, because they will sober-up even the coldest

utilitarian minds among us.

Today, the number of confirmed

COVID-19 cases in New

York state are at a staggering 320,000+ and rising; the

number of deaths attributed to the virus nears 25,000. And, of

these, New

York City accounts for nearly 19,000 deaths. New York state has a

death rate of 126 per 100,000 people; the

city itself has a death rate of 219 per 100,000. Even if some of my

libertarian colleagues wish to dismiss 20% of these casualties because they are

typically listed under the category of "probable" rather than "confirmed"

deaths, that still means that in excess of 20,000 people in my home state are dead from

this virus in two months. We need to put this in perspective because I'm tired of

hearing how accidents kill more people in a year or how influenza and pneumonia

kill more people in a year, and nobody talks about it. In a typical year, like,

say, 2017,

7,687 people died in accidents and 4,517 people died from the flu and pneumonia

in New York state. COVID-19 has now killed more than the annual total of

these two leading causes of death combined in this state in just two

months. It is therefore astonishing to me how any person would indict the

state's healthcare system as somehow to blame for the horrific death

toll---whatever problems that are inherent in that system---especially when it

has been stretched to its limits, and its doctors, nurses, and first responders

have worked heroically to treat and save so many lives.

According to the Centers

for Disease Control and Prevention, throughout the United States,

there are over 1.1 million cases, and over 67,000 deaths. But Ryan

McMaken drives home a crucial point that is fully cognizant of the

catastrophe that has befallen New York and New Jersey, in particular. As of

April 25, 2020, New York and New Jersey accounted for more than 51 percent of

the COVID-19 deaths in the United States. All the other states combined

constituted less than 48.5 percent. "The difference becomes even more stark as

we move west and south. New York's death rate is now 22 times as large as

Florida's and 25 times that of Alabama. Many states now report total deaths per

100,000 that are one-thirtieth the size of New York's toll. ... Were New York a

foreign country, the US's total death rate from COVID-19 would be cut by 36

percent." McMaken argues persuasively that "[t]his wide variation means that

other variables---like population density or subway use---were more important.

Our correlation coefficient for per-capita death rates vs. the population

density was 44%. That suggests New York City might have benefited from its

shutdown---but blindly copying New York's policies in places with low COVID-19

death rates, such as my native Wisconsin, doesn't make sense."

McMaken asks an important question, though: "Indeed, these numbers are so high

that one wonders if deaths are even being counted properly, or if there is

something about New York's medical infrastructure that is especially inferior.

Perhaps New York is home to a particularly virulent strain of the disease.

Perhaps the disease was in circulation for far longer than the experts insist is

the case. The experts don't know the answers to these questions."

Sadly, some of the comments following McMaken's essay only escalated my

irritation. Some commentators were practically gleeful that NYC was experiencing

such a terrible loss of life---punishment, it appears, for allowing "illegal

immigrants" into our domain as a "sanctuary city."

It should be noted that the first hotspot in New York state was not even in New

York City proper. It was at a synagogue in New

Rochelle. Cases swiftly navigated toward "Jew York City" (yes, that's

what one "libertarian" told me before I hung up on him). So let's Blame

the Jews! Or blame those damn Italians who came here in droves during

and after the holidays to visit their families in New York City! Or blame

the gays---who were also responsible for bringing us HIV/AIDS. Or

let's just blame

New York City itself and its "New

York Values"---you know, values such as openness, cosmopolitanism,

acceptance, tolerance.

When people attack this city for its virtues, they are attacking the American

dream. They speak of liberty but they'd prefer to extinguish that Torch in the

Harbor. New York has taken the brunt of this crisis because it is the city that

people from all over the world want to visit. It is among the greatest

cultural and economic accomplishments in human history. For this New Yorker,

it's the greatest city on earth.

So let's examine some more facts that might help to explain why New York has

been so badly hit. As we all know, the virus was first manifested in the city of

Wuhan, China (and scientists continue to debate whether this was a transmission

from another

species or some kind of laboratory

experiment gone wrong). The CDC reports

that "after Chinese authorities halted travel from Wuhan and other cities in

Hubei Province on January 23, followed by US restrictions on non-US travelers

from China issued on January 31 (effective February 2), air passenger journeys

from China decreased 86%, from 505,560 in January to 70,072 in February.

However, during February, 139,305 travelers arrived from Italy and 1.74 million

from" other European

countries, "where the outbreak was spreading widely and rapidly."

The pandemic

first hit Italy at the end of January, ramping up in February.

(Interestingly, northern Italy has the largest

concentration of Chinese people in all of Europe, many of them involved

in business travel between China and Italy.) The vast majority of

travelers from Italy and other European countries came to New York City. Gotham

attracts an average of 65 million tourists each year---seeded primarily through

the three major airports in the metropolitan area: Newark, JFK, and

LaGuardia---and of these over 13.5 million came from overseas last year alone.

During the holiday season, about 800,000 tourists per day flood into

Rockefeller Center. Citing the CDC study, New York Governor

Andrew Cuomo stated: "When you look at the number of flights that

came from Europe to ... New York and New Jersey during January, February, up to

the close down, 13,000 flights bringing 2.2 million people" came into the

metropolitan area. From February 5 through March 16, 2020 alone, nearly

4,000 flights from Europe landed in JFK and Newark Airports, a

sobering statistic, given that the vast majority of coronavirus strains were

identical to the ones from Europe. And there is growing evidence that mass

transit (especially the subways)

became one of the chief transmission belts for the spread of the virus. The

subways handle between five and six million riders per day, and given

that many Latinos and African Americans work at jobs that are least likely to be

resituated remotely, it is no coincidence that these communities, which depend

on the subways for transit to and from their places of employment, have been

disproportionately hurt by this pandemic.

But during this pandemic, as in the days following 9/11, we are seeing once

again how New Yorkers are helping their neighbors in every way they know how,

and as safely as they can. We are not sheep being led to the slaughter. We are a

rowdy bunch. And it didn't take a political lockdown for the vast majority of

New Yorkers to respond to the facts of this pandemic. The overwhelming

majority of us are social distancing or self-quarantining when symptomatic

because it is the most rational thing to do under the conditions that

exist here. But through it all, from the growing networks

of mutual aid that deliver food to those in need to those working on

the healthcare

frontlines, this city is showing the guts for which it is known.

Through the concerted efforts of local authorities, healthcare workers, first

responders, and the people of this city, things are improving. We are no longer

seeing daily deaths hovering at the level of 800 per day. Hospitalizations are

down. Intubations are down. New cases are down. And we are now seeing fewer than

300 individuals dying each day. Will there be a second wave? If I had a crystal

ball, I'd be able to answer that question.

Opening Up

Moving forward, one of the key principles that must guide our commitment to

fully re-opening our communities is that one size does not fit all. The

New York "model" is not applicable to Alaska, where only 370 confirmed cases of

COVID-19 have been identified and only 9 people have died. Given that there are

at least vestiges of federalism still in effect in this country, and that

centralized institutions at the federal level often cannot respond with as much

immediacy to the situation on the ground as do localized institutions (a

Hayekian insight, so-to-speak, applied to governmental entities), different

localities will muddle through in different ways, with different timelines. Some

regions, like the Northeast corridor, will work in concert because they are far

more interconnected in such ways that the actions of one state will invariably

impact on other states within that region.

Yes, everything in this world is interconnected in the wider context. If

somebody had told me that a December 2019 virus in Wuhan, China would have led

to 25,000 deaths in New York by May 2020, I would never have believed it. But

contexts are continually evolving over time.

Paying attention to context means paying attention to changing contexts.

This is not some NORAD computer playing

"Tic Tac Toe" (as in the 1983 film, "WarGames"),

where the context never changes and the outcome is always a stalemate.

Politicians on both sides of the aisle, who have bungled this from the very

beginning, understand that they cannot kill the host, the social economy, upon

which their very existence depends.

As Pete

Boettke argues, a genuinely realist approach must navigate between

the false alternatives of "Romance" and "Cynicism"---the Scylla and

Charybdis---that we typically face in all crises that have led to an

augmentation of government power:

Romance lead[s] us astray by framing political leaders as saintly geniuses,

whereas Cynicism leads us astray by framing the system as completely corrupt and

devoid of any hope for improvement. Nothing in the Humean dictum that in

designing institutions of government we should assume all men are knaves is

either descriptive or hopeless. In fact, the hope in that dictum comes from ...

minimizing the loss function in the design from the possibility of knaves

ascending to power. It is from constructing the institutional rules of our

governance such that bad men can do least harm, rather than assuming that only

the best and brightest among us will rise to leadership, or that whatever system

of governance we talk about it will devolve into corruption and immorality.

Realism forces us to reason through the tricky incentives that actors face in

making their decisions. Realism also forces us to place the theorist in the

model itself. Why do theorists choose the theories that they do, why do they

make the statements that they do. The old political science "law" that where you

stand is a function of where you sit, is just as true for scientists and

academics as it is for Senators and Congressmen.

I fully agree with Pete that this pandemic has become a "testing ground" for our

biases and ideas. The first step toward freedom is liberation from our

ideological blinders. That doesn't mean a renunciation of our core values and

convictions. It is an admission that human beings are

fallible yet capable creatures that when given freedom from the oppression of

servitude (Crown), dogma (Altar), violence (Sword), and poverty (Plough) ...

unleash their creative energies and lead to improvement in not only the material

conditions of humanity but physical, spiritual and interpersonal. True radical

liberalism is an emancipation doctrine, and seeks to cultivate a social system

that exhibits neither discrimination nor dominion, and promises a social system

that strives to minimize human suffering while maximizing the chances for human

flourishing.

***

On the wall next to my desk, I have a small plaque, gifted to me by my family

doctor when I was a young boy, who had emerged from life-saving surgery, after

suffering for fourteen years without any diagnosis. It's an "Indian Prayer" and

it says: "Grant that I may not criticize my neighbor until I have walked a mile

in his moccasins."

I have seen the pain caused by this pandemic on every level, though as someone

who has had 60+ surgeries in his life to combat the side effects of my own

illness, I naturally share an affinity with those who become sick, for any

reason. I have seen neighbors to the right of me and neighbors to the left of me

who are sick, dying, or dead.

But I am not oblivious to the other pain that is being experienced by people who

are not sick. They too are my neighbors. They are out of work, their

unemployment checks are held up, some of them are too "proud" or ashamed to even

apply for food stamps, until they realize that they can't afford to feed their

own children without some help.

The human costs of this pandemic run deep, among families that are grieving over

the loss of loved ones, among those whose businesses may never recover, whose

jobs may never reappear, and whose dreams have been aborted. I have seen too

much suffering on both sides of this divide.

But if we are to make the

case for a new radicalism, each of us must be willing to engage in

self-critique, to make transparent and examine our own biases. This must be

coupled with a willingness to embrace the very real human need for

empathy, the ability to truly share and understand the struggles of other

individuals, especially those with whom we may disagree.

Without that empathy, I fear that the things that divide us may become

irreparable not just to the libertarian project, but to the ideal of human

freedom that we seek.

Postscript:

Thank you to Rad

Geek for mentioning the Jeffrey Harris study cited here.

Also my thanks to Amir Abbasov for translating this blog essay into Azerbaijanian.

Postscript (12

May 2020): A few additional points were raised by this post on the Facebook

Timeline; below are some of my comments in response to reader's questions. One

reader wrote that the claim by Boettke and Hayek was "over stated. If there are

plenty of ordinary cases where government handling of emergencies is not

intended simply to augment state power, we can't conclude that that's the case

in large scale extraordinary emergencies." I responded:

I would say that this is why we need to study history. Once again, it's evidence

that must guide us, not an ideological blueprint. When I look at large-scale

events in the twentieth century like World War I, the Great Depression, and

World War II, for example, it's pretty clear to me that each of these augmented

state power enormously in the United States, and left institutions in place that

allowed for further expansions of state power when the crises were over. In

fact, the War Collectivism of World War I (part of the War Industries Board,

which basically put in place a corporate state of sorts, while the country was

on war footing), laid the basis of the corporatism of the New Deal programs,

which were further centralized by the War Production Board in World War II. And

the policy of "permanent war for permanent peace" throughout the post-war, Cold

War era is what ultimately led even Dwight Eisenhower (hardly a radical

libertarian) to warn of the excessive influence of a vast military-industrial

complex. His 1961 farewell speech is worth quoting at length, for its insight

into the ways in which this complex was distorting American social life:

"Until the latest of our world conflicts, the United States had no armaments

industry. American makers of plowshares could, with time and as required, make

swords as well. But we can no longer risk emergency improvisation of national

defense. We have been compelled to create a permanent armaments industry of vast

proportions. Added to this, three and a half million men and women are directly

engaged in the defense establishment. We annually spend on military security

alone more than the net income of all United States corporations.

"Now this conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms

industry is new in the American experience. The total influence---economic,

political, even spiritual---is felt in every city, every Statehouse, every office

of the Federal government. We recognize the imperative need for this

development. Yet, we must not fail to comprehend its grave implications. Our

toil, resources, and livelihood are all involved. So is the very structure of

our society.

"In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of

unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial

complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and

will persist. We must never let the weight of this combination endanger our

liberties or democratic processes. We should take nothing for granted. Only an

alert and knowledgeable citizenry can compel the proper meshing of the huge

industrial and military machinery of defense with our peaceful methods and

goals, so that security and liberty may prosper together."

Pretty good for a Republican...

I added:

My post certainly sees the current pandemic as a large-scale extraordinary

emergency, and it specifically warns against viewing this through the lens of

"hoax" and "conspiracy" theories, which reduce this to a power-grab by the

state. It also accepts the possibility that, like any emergency, this can be

used as a pretext by political and economic actors in ways that could augment

state power in the long-run, something that requires our vigilance. Still, it's

clear to me that Boettke does not adopt the kind of strict dualism that one

finds in too many libertarian discussions of this kind. He himself makes clear

that we can't be led "astray by framing political leaders as saintly geniuses,"

or "by framing the system as completely corrupt and devoid of any hope for

improvement," and that to assume that all political actors are "knaves is either

descriptive or hopeless." He explicitly rejects the assumption that "whatever

system of governance we talk about ... will devolve into corruption and

immorality." Yes, he would prefer an institutional order "such that bad men can

do least harm"---but who wouldn't?

I think that natural catastrophes certainly fall under the category of

large-scale extraordinary emergencies; I think of things like earthquakes,

Hurricane Katrina, even Superstorm Sandy, which devastated the tri-state area.

And I think that given the conditions that exist, it was necessary for

the institutions in place to step-up actions to save populations and property. I

don't think it is necessarily the case that state action under those

circumstances is a power-grab. I also think that a lot can be said for the

extraordinary efforts made voluntarily by individuals and through networks

of mutual aid, which saved the lives of countless numbers of people.

Postscript (25

May 2020): Irfan Khawaja addresses "Puzzles

of the Pandemic: 'The Nursing Home Massacre'", in which some folks

have blamed NJ Governor Murphy and NY Governor Mario Cuomo for having "spiked"

the deaths in their respective states by returning from various hospitals

recovering COVID-19 elderly patients to the nursing homes from which they came.

I responded in the comments section:

Well, if you listen to the folks at Fox News, Cuomo, Murphy, etc. purposely sent

patients, who previously lived in nursing homes and were subsequently

hospitalized for and designated as having recovered from COVID-19, back into the

nursing homes from which they came. The Fox Folks claim that this was some

diabolical plot to kill off the elderly population and/or to inflate the death

tallies in NY and NJ, since many of those who were designated as "recovered"

were still capable of infecting others. But yes, aside from the Fox Folks, there

are legitimate questions about the wisdom of the policy of sending these

patients back to the nursing homes---though it is not at all clear that the

infection rate within nursing homes was strictly a result of this policy.

Indeed, it is entirely possible that the

spike in nursing homes was as much the result of nursing home residents coming

into contact with asymptomatic infected staff.

The initial policy was adopted because the hospitals in NY were being overrun

and taxed to a catastrophic degree, and when the USS Comfort arrived, and the

Javits Convention Center (along with four other centers in the outer boroughs)

were set up, they were opened to take in patients who were not sick from

Coronavirus; they were to be places where folks facing traumatic medical

problems unrelated to the virus could be cared for under "virus-free" conditions. The private and public hospital network were to shoulder the burden

of the growing population of sick and dying patients from the virus, while these

other places (the Comfort, Javits, etc.) would provide medical care for those

not infected with the virus, but in need of urgent medical care (so-called

"elective" surgeries were all postponed, but, obviously, there are many other

medical problems that people face, for which they require treatment, in medical

facilities that are not death traps for those with underlying pre-existing

conditions).

Though the official reversal came at the beginning of May, the

policy actually started to change at the beginning of April. It was

at that time that the Comfort and the Javits Center were finally opened up to

care for the overflow of COVID-19 patients.

But, yes, the damage was done. And I suspect that's what Cuomo's mea culpa is

about. He's certainly not in agreement with the Fox Folks that his policy was

designed to kill people; but it was a policy that was shaped by the exponential

growths in hospitalizations and intubations that were happening in late March

and early April, until the state hit a plateau of 800-1000 deaths per day. Once

it became clear that the healthcare network, as taxed as it was, would not

collapse, and that these other facilities could take in COVID-19 patients, the

practice of sending recovering nursing home patients back into nursing homes

started to change. And extra precautions were put into place at the beginning of

May, as Michael indicates above.

Clearly, mistakes have been made at every level of government; but it's a huge

leap to characterize something that was a tragic mistake to viewing it as a

criminal act. I live in NY; I've lost neighbors, a cousin, friends, and even

cherished local proprietors, to this horrific disease. There's a lot of blame to

go around; those most at fault, however, were the folks who denied that there

was even a virus at work, that the whole thing was a hoax, and that one could

just wash it away with a little detergent or by mainlining bleach.

Finally, I note that yesterday (27 May 2020), the United States officially

reached a grim milestone: Over 100,000

deaths from coronavirus-related illnesses. What can one say in the

face of such a horrific statistic? Stay safe. Wear masks. Practice social

distancing. The motto of the day remains "Better

to be six feet apart, than six feet under."

Postscript (14

July 2020): This blog essay was cited by John Authers (in the italicized words

below) at Bloomberg.com ("The

Golden Rule is Dying of Covid-19)."

Libertarians often face criticism that they are justifying selfishness, and

disregard for others. Such incidents confirm the stereotype and embarrass

many libertarians. Resistance against incursions by an untrustworthy state

does not justify violence against people who wear masks, or even going maskless

in public.

Posted by chris at 01:42 AM | Permalink |

Posted to Culture | Dialectics | Film

/ TV / Theater Review | Foreign

Policy | Politics

(Theory, History, Now) | Rand

Studies | Religion | Sexuality