NOTABLOG MONTHLY ARCHIVES: 2002 - 2020

| MAY 2020 | JULY 2020 |

Celebrating the Ray Harryhausen Centenary

Today marks the centenary of the birth of master special effects wizard Ray

Harryhausen---born on this date in 1920. Turner

Classic Movies is celebrating tonight with a line-up of some classic

films that feature his remarkable stop motion animation.

I can't even begin to put into words what Harryhausen's films meant to me

growing up. So it's best to let his genius speak for itself! From the 1963 film,

"Jason

and the Argonauts," augmented by a superb score from Bernard

Herrmann.

Posted by chris at 10:35 PM | Permalink |

Posted to Culture | Film

/ TV / Theater Review | Music

Song of the Day #1794

Song of the Day: You've

Made Me So Very Happy features the words and music of Berry

Gordy, Frank

Wilson, Patrice

Holloway, and Brenda

Holloway, who recorded this song

in 1967 [YouTube link]. The song barely cracked the Top 40 on both

the Billboard Hot 100 and the R&B Singles Chart. But it was a featured

selection on the

jukebox of the Stonewall

Inn, which, on

this date, was subject to a police

raid, something that was typically aimed at private establishments

catering to same-sex clientele. Such bars were often denied liquor licenses or

harassed simply because it was illegal for same-sex couples to hold hands, kiss,

or dance together ("lewd

behavior"). This particular bar was owned and "protected" by the Genovese

crime family, which paid off police officers from the Sixth

Precinct to look the other way. Corrupt cops would often get payola

to tip off the bar if there were any impending raids. But no tip offs came on

this night. The police entered the bar, roughed up employees and patrons, and

even arrested people for not wearing "gender-appropriate

clothing" (something that was actually against the law at the time).

The patrons had had enough. They pushed back and touched

off six nights of rioting, fighting for their very right to exist and

to pursue their own happiness. Though there

were many other precipitating events prior to 1969 involving many brave

activists, Stonewall remains

the singular "nodal

point" that gave birth to Pride

Day celebrations the world over (today, to the date, is, in

fact, the

fiftieth anniversary of the first Pride March in 1970 that marked the first

anniversary of the Stonewall uprising). In the end, however, this

date celebrates the birthright of every human being to pursue their own vision

of personal happiness, without fear of state or social oppression. In keeping

with our Summer Music Festival (Jazz Edition), we mark this occasion with

several jazz-infused versions of this song, chief among them the classic Blood,

Sweat, and Tears jazz-rock rendition [YouTube link], released the

same year as the Stonewall

Rebellion, rising to #2 on the Billboard Hot 100. And check

out renditions by song stylist Nancy

Wilson, pianist Ramsey

Lewis, clarinet legend Benny

Goodman, the Lasse

Lindgren Big Constellation and trumpeter Chet

Baker [YouTube links] (from his very commercial album, with the

clever title of "Blood,

Chet and Tears").

Posted by chris at 12:01 AM | Permalink |

Posted to Culture | Music | Politics

(Theory, History, Now) | Sexuality

Song of the Day #1793

Song of the Day: A

Little Less Wonderful [YouTube link], words and music by my dear

friend Roger

Bissell, is highlighted today in honor of his

birthday! This song, written in 1982, features vocals by Roger's

kids (Charlie, Rebecca, Andrew, and Daniel) and gospel singer, Mike

Allen. Roger provides

the scat-singing, whistling, finger snaps, and "mouth percussion" (sounds

perverse, I know). This is a sweet track from the 2010 album, "Reflective

Trombone." And for a loving twist on the tune check out this

George Smith-produced video version [YouTube link]. To my brother

from another mother: Many more happy and healthy returns, with love! Keep

bringing more wonderful music (and many more wonderful ideas) into our world!

Song of the Day #1792

Song of the Day: Captain

Senor Mouse, composed by jazz keyboardist extraordinaire Chick

Corea, made its debut on two 1973 albums: "Hymn

of the Seventh Galaxy" with Return

to Forever (featuring Bill

Connors on guitar, Stanley

Clarke on bass, and Lenny

White on drums) and with vibraphonist Gary

Burton on the duet album "Crystal

Silence" (and in the 2008

Grammy Award-winning live set, "The

New Crystal Silence"). Check out this Chick composition

in all its wonderful renditions: with Return

to Forever and with Gary

Burton in studio and live

settings, as well as covers by guitarist

Al DiMeola, guitarist

Martin Taylor and bassist Peter Ind, guitarist

Kevin Eubanks, and Gordon

Goodwin's Big Phat Band [YouTube links].

Coronavirus (27): Majority Rules NY

As coronavirus cases ebb in NY, and are spiking elsewhere in the country, I had

a chance to catch up with my friend Pasquale Cascone (who lives downstairs from

me!), and his "Majority

Rules NY" crew [YouTube link], which describes itself as follows:

Follow us on Instagram @majorityrulesny ... Message us some topics you'd like us

to address. Check us out on iTunes, Spotify, TuneIn radio, iHeartradio, Google

podcasts for more episodes from before we went to video and audio. We are a show

that relates to all of us in between the full blown adult phase of life and the

last ounce of youthfulness and trying to find the perfect balance.

This video made on 26 April 2020 is just a bunch of neighborhood guys who will

bring a smile to your face. Pasquale's discussion of living as an essential

worker during a time of "f&c*ing chaos" will give you a chuckle, even in the

midst of a world turned upside down. This is no Theatre

of the Absurd---since you'll find some nuggets of wisdom, and lots of

laughs, while listening to these guys thrash it about.

Posted by chris at 07:57 PM | Permalink |

Posted to Culture | Politics

(Theory, History, Now)

Song of the Day #1791

Song of the Day: ABC is

credited to "The

Corporation"---that Motown group

of musical creators who included Berry

Gordy, Freddie

Perren, Alphonzo

Mizell, and Deke

Richards. This song was the second of four consecutive Jackson

Five songs to hit #1, and alphabetically, it is at the beginning of Billboard's

all-time #1 hits. Eleven years ago today, Michael

Jackson died tragically. Last year, I wrote an

essay addressing his legacy and controversial life; this year, I mark

this anniversary with memories of a happier time. Check out the

original J5 single and the

Jackson Five appearance on "The Ed Sullivan Show" on 10 May 1970. But

in keeping with the theme of our Summer Music Festival (Jazz Edition), check

out this

big band arrangement by Jim McMillen from the album, "Swingin' to Michael

Jackson: A Tribute".

Posted by chris at 12:48 AM | Permalink |

Posted to Music | Remembrance

On Statues, Sledgehammers, and Scalpels

"If all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail ..."

As protests in the wake of the recent murder of George Floyd have spread

throughout the United States (and even throughout the world)---something I

addressed in my essay, "America:

On Wounded Knee"---I've been participating In several Facebook

discussions, nearly all of which have been unpleasant. Nevertheless, I wanted to

add this postscript to a very heartfelt post for the record, most of it

drawn from these various Facebook threads.

I recently saw for the umpteenth time the 1991 Oliver

Stone-directed film, "JFK",

which opened with this quote from American author and poet Ella

Wheeler Wilcox:

To sin by silence, when we should protest, makes cowards out of men.

A more prescient observation in these times would be hard to find. It is

unacceptable to be silent in the face of injustice; standing by the courage of

our convictions---and protesting against tyranny anytime we see it---is a

necessity for any of us who care about human freedom and dignity.

But as my previous essay made clear: the means of protest often make all

the difference moving forward in terms of the shape of things to come.

Much has been made of the tearing down of confederate statues that pepper the

states of the former confederacy; I have discussed this several times before,

most notably in this

post. I think that these symbols of oppression are reprehensible. One

important point has been obscured in the discussion of the statues of the

confederacy in particular. Most of those statues were not built in the

wake of the Civil War to commemorate the "heroes" who fought in the "war of

Northern aggression." They were built during times of extreme civil rights

distress, with the

clear purpose to intimidate African Americans who were getting too

"uppity" in their struggles for human freedom.

Nevertheless, the historian in me sees the controversy over these statues as "teachable

moments." As relics of a bygone age, their preservation in some

form---a museum or some other gallery---can provide people of different walks of

life an opportunity to understand the cultural narratives embodied in these

symbols of hate.

As protests have spread, so too has the ire of the protesters, who turn toward

statues of such figures as Christopher

Columbus, striking at the heart of the brutality of the European

"discovery" and colonization of the Americas and the destruction of indigenous

peoples. I understand the anger and actions of protesters with regard to

Columbus and what follows is not an apologia for any of his misdeeds. It

is, however, an attempt to contextualize the push-back that inevitably follows

when different narratives collide.

Statues, like all symbols, convey different meanings to different peoples,

giving rise to conflicting narratives. Knowing something about the Italian

American experience, I fully understand the attitudes of many Italians,

especially of an older generation, who came to America, viewing Columbus as

having opened up a "New World" to which they could emigrate, in search of

greater opportunities. No matter how incorrect their perception of Columbus was,

it still remained a powerful symbol for that group of immigrants, among them my

paternal grandparents.

As I have observed here,

Italian immigrants were met with ethnic prejudice of a sort that made them

second only to African Americans in terms of the number of lynchings they

experienced in the years between 1870 and 1940. It was a "murderous spree" that

spanned states from Colorado to Mississippi to Illinois to North Carolina to

Florida. And when they weren't being lynched by those who saw them as dangerous

"others", harboring a "foreign" religion (Catholicism) and "anarchist"

tendencies (Sacco

and Vanzetti, anyone?), they were targeted by their own people. The

so-called Black

Hand extorted "protection" money from residents and businesses alike

(that is, protection against Black Hand thugs who would target any Italians who

refused to buy into the form of "protection" they offered, in the face of

indifference from the predominantly Irish

police force in NYC.) The shift away from outright extortion to more

subtle forms of extortion (through oaths of mutual loyalty) came with the

rise of Mafia organizations---something accurately portrayed in the

story of the rise of the young Vito

Corleone in "The

Godfather, Part II".

So given the symbolism of Columbus to many Italian Americans, I can understand

the predictable push-back toward those who have targeted statues of the

explorer. It will probably take a generational shift in the culture of Italian

Americans before anyone could entertain even the possibility of dismantling that

statue reigning over Columbus Circle in NYC (which has had that name since the

late 1800s). But what some folks don't understand is that the annual Columbus

Day Parade is, essentially, an annual Italian American Day Parade, in the same

way that there is a Greek Independence Day Parade, a Puerto Rican Day Parade, a

St. Patrick's Day Parade, and a Pride Day Parade. Each of these parades may be

rooted in an historical event, culture, or person(s), but ultimately, they

become extensions of the groups and traditions they are meant to celebrate. I

don't think I've watched a single Columbus Day parade where the Grand Marshall

extolled the "virtues" of Columbus, colonialism, or Native American genocide.

It's always focused on the Italian American contribution to American culture and

life... and I don't think this will change, at least not in my lifetime.

Nevertheless, the practice of taking sledgehammers to statues has now moved from

symbols of the confederacy and symbols of European colonization to symbols of

the founders of the American republic, most of whom were, indeed, slaveholders.

The toppling of statues of George

Washington has been met with applause from many of my libertarian

friends and colleagues. Even the NYC City Council is considering removing the

statue of Thomas

Jefferson, another American revolutionary who owned slaves in his

lifetime.

Jefferson surely was an imperfect, flawed human being, a man who owned slaves

and may

have fathered children with one of them. But he was also the author

of these words in the

founding document of the American republic:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that

they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among

these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. That to secure these

rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from

the consent of the governed, That whenever any Form of Government becomes

destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish

it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles

and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to

effect their Safety and Happiness.

That these words would ultimately serve as the inspiration for those seeking to

abolish the very institution that Jefferson the man sustained is, in itself, a

testament to his enduring intellectual legacy. Even Jefferson would have

understood the need for people to rise up, protest, and rebel against injustice.

"The tree of liberty," he

famously declared, "must be refreshed from time to time with the

blood of patriots and tyrants. It is it's natural manure."

Ironically, even a thinker as far left as Slavoj

Zizek has emphasized the importance of treating Jefferson as

qualitatively different from, say, Robert E. Lee. As he wrote in Like A Thief

In Broad Daylight: Power in the Era of Post-Humanity (H/T to my pal Eric

Fleischmann):

The point is not just to debunk the War of Independence as fake: there

undoubtedly is an emancipatory dimension in the works of Jefferson, Paine, and

so on. In spite of being a slave owner, Jefferson is an important link in the

chain of modern emancipatory struggles, and one is justified in claiming that

the struggle for the abolition of slavery was basically the continuation of

Jefferson's work. Jefferson was a different kind of man from Robert E. Lee, and

the inconsistencies in his position just demonstrate how the American revolution

is an unfinished project (as Habermas would have put it).

It was this project that led Benjamin

Tucker to identify anarchists as "unterrified

Jeffersonian democrats."

So if we're going to view every flawed eighteenth century individual through the

20/20 hindsight of 2020, at least let's get some corrective lenses to help us

grasp more fully the nuances of the larger historical and systemic context. With

the use of every sledgehammer to bring down every statue, it is essential to

retain the intellectual scalpels required for a more delicate, surgical

dissection of America's past: its flaws and its virtues, its injustices and its

promise.

Ironically, there is an historical figure that is, in many ways, more flawed

than Jefferson, and yet, in the narrative of American history, that figure looms

large over the emancipation of African Americans from slavery: Abraham Lincoln.

On almost every level, Lincoln

was neither a model President nor a model libertarian. And yet,

despite his nationalist economic policies, his suspension of habeas corpus and

his odious racialist views, his soaring

rhetoric of freedom rang clear to generations

of African Americans. Before his assassination in 1865, he fought

hard to pass the

Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution that would forever abolish

slavery in the United States. It led many to view him as The

Great Emancipator, and gave the

vast majority of African Americans a reason to vote Republican until the New

Deal era.

And so, in Washington, D.C., there sits a huge memorial to Abraham Lincoln---one

that overwhelmed me when I saw it as a five-year old kid who toured the historic

district for the first time. When opera singer Marian

Anderson was denied the opportunity to sing at Constitution Hall because

she was blocked by the Daughters of the American Revolution, she sang on the

steps of the Lincoln Memorial and made history. When Martin

Luther King, Jr. marched on Washington in 1963, he gave his legendary

"I Have a Dream" speech in the shadow of that same memorial. Given the history

of that memorial in the struggle for civil rights, and despite the

terribly flawed man to whom that memorial was erected, one has to ask: Do we

burn it down to the ground because of the flaws of the man, or keep it as part

of our historical memory precisely for its evolving significance to generations

of people yearning to "breathe

free"? ("I

can't breathe" is indeed far more symbolic here than a mere call for

simple survival: it is the very negation of life and liberty in every meaningful

way.)

When the sledgehammer is wielded without any consideration of the larger context

of American history, the wider cause of justice for all cannot be served.

Over the last century or so, we have seen the atrocities committed by "top-down"

canvas cleaning, from the Nazis to the Soviets to the Maoists to the Taliban.

"Bottom-up" canvas cleaning is an entirely different species. It is an

understandable reaction against systemic and institutionalized

oppression. But in cleaning the soiled canvas of the American experience by

toppling the statues of flawed men, a transcendence is required, or we risk

toppling the ideals that some of these men---especially the American

founders---extolled. These ideals, if followed to their logical conclusion, are

the most potent weapons in fighting injustices around the world.

My friend Roderick

Tracy Long recently quoted Michel

Foucault, and it's worth repeating here:

My point is not that everything is bad, but that everything is dangerous, which

is not exactly the same as bad. If everything is dangerous, then we always have

something to do. So my position leads not to apathy but to a hyper- and

pessimistic activism. I think that the ethico-political choice we have to make

every day is to determine which is the main danger. ("On the Genealogy of

Ethics: An Overview of Work in Progress," afterword, in Hubert L. Dreyfus and

Paul Rabinow, Michel Foucault: Beyond Structuralism and Hermeneutics, 2nd

ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983).

This is a call to focus on the main dangers that surround us, challenging

them radically, at their fundamental roots, with all the courage demanded

of us in the face of injustice. Destroying statues is easy; the truly Herculean

task before us is to build alternative statues, symbols, and structures of

meaning that do not replicate the injustices of the past, and that move toward

the realization of the very ideals of freedom, equality, and social justice

embraced by some of those flawed fellows who pledged their lives, fortunes, and

sacred honor to defeat the tyrannies of their time.

Postscript (22

June 2020): Some discussion of these issues took place on Facebook, and I

reproduce some of my comments from the various threads here. My dear friend Ryan

Neugebauer remarked: "Imagine thinking society should be a giant museum where

you have to preserve everything as it is for all times and places. No change,

you must always see the past wherever you go. I would not want to live under

such thinking. It's ridiculous also because every era ends up replacing previous

ones. Even the ones you think you are preserving replaced ones before them."

I replied:

I agree, and this is is why we have museums---where relics of the past might sit

and be more properly contextualized. But I do think a greater context needs to

be grasped here (and I'm not suggesting that the current folks tearing down

monuments are on a par with the Taliban or the Maoist cultural revolutionaries).

Nevertheless, massive social change is not going to be achieved by the kind of

"canvas cleaning" that would demand the dynamiting of Mount Rushmore (the way

the Taliban destroyed the Buddhas of Bamyan) or some Maoist-like cultural

revolution, which tried to wipe out every last vestige of the past as if it

didn't happen, taking thousands of lives along with it.

We don't have to forever preserve the past in temples glorifying bad acts or bad

people. It is easy to bring down a statue or a monument with 20/20 hindsight and

2020 sensibilities; the more difficult task is building new monuments that take

on greater meaning and symbolism for a new generation in affecting the kind of

cultural change upon which any radical political change must ultimately depend.

Look, all I'm saying is: The whole goddamn country's history is drenched in

blood "from sea to shining sea." And there probably isn't a society on earth

that isn't drenched in blood. Here alone we have seen massive systemic violence

directed against indigenous populations, "imported" populations (as in slavery),

immigrant populations, or populations of marginalized people (LGBTQ+).

Ultimately, you can't turn back the clock; you can try to topple symbols or

contextualize them, but the really demanding project is in building alternative,

parallel, more powerful symbols to supplant the older ones---without necessarily

destroying everything from the past. Folks can make this a "teachable moment"...

creating anew, without aiming to destroy every last vestige of the past. It does

not work. It never has. It never will.

Social change is always messy---but thank goodness it's not a "top down"-

dictated social change that we are currently witnessing. We are far more likely

to see a better outcome even from messy "bottom-up" and "spontaneous" excesses

than anything we would witness if "change" were dictated by folks in high places

with guns and gulags.

On another thread was reproduced the famous Lord

Acton passage that, in full, states:

Power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Great men are

almost always bad men, even when they exercise influence and not authority;

still more when you superadd the tendency of the certainty of corruption by

authority.

... to which I responded:

Mostly applicable to politicians and rulers. Not to comedians, like, say, "The

Great One" (Jackie Gleason). All depends on the context. :)

Jeez... even that got push-back! When one reader suggested that maybe it

applied to Gleason as well, since his oft-repeated line---"One of these days,

Alice ... pow!"---glorified "domestic violence for laughs", I replied:

Except that in the end, Alice always proved to be the wiser one. She was

practically a feminist hero, way ahead of her time, who was ultimately always right.

Not to mention the number of laughs Alice got, which far "outweighed" anything

Ralph Kramden could ever say, since she targeted his "weight" for more laughs

than any "Bang, Zooms" that came out of Ralph's mouth. More than that, her

put-downs of him were far more biting and riotous than anything he could ever

say. If somebody ever really did an examination of those "Honeymooners" scripts

and saw how Alice handled "the King of the Castle", they'd easily see just who

was really the "king" of that castle. I'd go one step further: Show me one

other 1950s sitcom that portrayed a stronger woman than Alice Kramden. In an

era dominated by "Father Knows Best" and such, she was truly in a class by

herself.

... and the beat goes on ...

Posted by chris at 02:19 AM | Permalink |

Posted to Culture | Dialectics | Education | Film

/ TV / Theater Review | Politics

(Theory, History, Now)

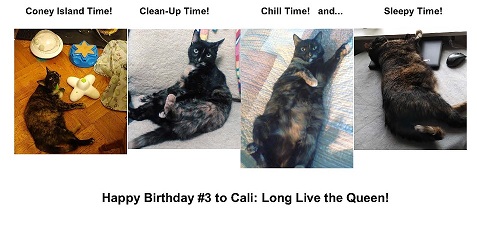

Cali Turns 3: Long Live the Queen!

Back on May 17, 2018, our little Cali the Cat entered our lives, only to

celebrate her first birthday with us on June

21st of that year. She has been a source of joy, mystery, entertainment,

hilarity, and love.

We celebrated the Terrible

Twos last year, but we've been warned by child

psychologists that the Threes can be Just as "Terrible", with

observations that are obviously just as applicable to cats as they are to kids!

For kids, "at two, they can barely talk. At three, they never shut the hell up."

Well, Cali hardly meowed when she was younger. Now she has a variety of

sounds that tell you exactly what she means.

For kids, "at two, they are distracted by a box of Gerber Puffs at the grocery

store. At three, they want to dictate your entire food list." Clearly applicable

to cats.

For kids, "at two, manipulation is the last thing on their minds. At three, they

own you. And they know it." Yep!

And that's why she's gone from a Diva to the Queen of this Castle!

Happy birthday to our baby! Many more happy and healthy returns, with mucho love

from all of us!

Finally, this proud Daddy is happy to say that his baby daughter wished him Happy

Father's Day after I kissed her belly... from which I escaped

unscathed! (And a Happy Father's Day to all the other Dads out there!)

Posted by chris at 12:01 AM | Permalink |

Posted to Blog

/ Personal Business | Frivolity

Song of the Day #1790

Song of the Day: What

is this Thing Called Love?, words

and music by the great Cole

Porter, was featured in the 1929 Broadway musical "Wake

Up and Dream," where it was introduced by Elsie

Carlisle [YouTube link]. At 5:44 pm, today, the Northern

hemisphere enters the Summer Solstice. And so begins the Fifth Annual Summer Music

Festival (Jazz

Edition). This entire summer, I'll be spotlighting jazz

recordings---from artists past and present. Ironically, long after my playlist

was set in stone for the festival, I discovered that TCM has been running a

wonderful series of "Jazz

in Film" (Mondays and Thursdays in June). This festival was also

planned long before recent

events, but it is a celebration of a genre that owes so much to the African

American experience---while transcending the divisions of social life

through the universality of music. Fortunately, for today, I get to highlight

one of the great contributions to the Great

American Songbook. Though this is going to be a Jazz Summer, I won't

be posting many jazz standards, since my ever-growing list of "Favorite

Songs" has been featuring such standards for sixteen years! But

today's song asks one of the most enduring questions of the human condition.

Musicians from every walk of life---every race, every ethnicity, every

gender---have explored their answers to that question in a variety of ways over

the years, including stride

pianist James P. Johnson, Fred

Rich and his Orchestra (featuring jazz violinist Joe Venuti and both Tommy and

Jimmy Dorsey), twice by jazz

guitar giant Django Reinhardt and legendary

jazz violinist Stephane Grappelli, the

Artie Shaw Big Band, guitarist

Les Paul, pianist

Dave Brubeck and alto saxophonist Paul Desmond, alto

saxophonist Cannonball Adderly, soprano

saxophonist Sidney Bechet and trumpeter Charlie Shavers, jazz

guitarist Joe Pass, tenor

saxophonist Stan Getz and pianist Kenny Barron, trumpeter

Clifford Brown, tenor saxophonist Sonny Rollins, and drummer Max Roach, jazz

violinist Thomas Fraioli, New

York Swing (with guitarist Bucky Pizzarelli, pianist John Bunch, bassist Jay

Leonhart, and drummer Joe Cocuzzo), the

McCoy Tyner Quartet (with tenor saxophonist Joe Henderson, bassist Ron Carter,

and drummer Al Foster), and pianist

Danny Zeitlin [YouTube links]. One of my favorite instrumental

renditions comes from jazz pianist Bill

Evans [YouTube link] from his 1960 album "Portrait

in Jazz"---with its trailblazing interplay between a trio of co-equal

improvisers, which included bassist Scott

LaFaro and drummer Paul

Motian. The album was recorded eight months after Evans's

collaboration with Miles

Davis in creating the best-selling

jazz album of all time, "Kind

of Blue." That revolutionary album was largely based on the

pianist's impressionistic, harmonic

conceptions and modal

approach, which led many to view Evans as

"the

principal creator of [the] album." There have also been some

wonderful vocal renditions of this Porter classic

by such artists as Sarah

Vaughan, Billie

Holiday, Frank

Sinatra, Ella

Fitzgerald, Anita

O'Day, Keely

Smith, and Bobby

McFerrin (with Herbie Hancock on piano) [YouTube link].

Posted by chris at 12:01 AM | Permalink |

Posted to Culture | Film

/ TV / Theater Review | Music | Politics

(Theory, History, Now)

Song of the Day #1789

Song of the Day: Scoob!

("Summer Feelings"), words and music by Lennon

Stella, Charlie

Puth, Invincible

(Producer), Alexander

Izquierdo, Charles

Brown, Simon

Wilcox and Lowell,

can be found on the soundtrack to the 2020 animated flick "Scoob!"

(short for Scooby

Doo). This duet, featuring Lennon

Stella and the deeply jazz-influenced Charlie Puth, is a precursor to

our Fifth

Annual Summer Music Festival (Jazz Edition). This year has been a

transformative one in so many ways and on so many levels; I've seen things that

I could never have even remotely predicted when I toasted

the New Year as the ball dropped in Times Square. I have refused

to stay silent and have spoken out about so

many issues over these many months; so I don't want to be accused of

being a

modern-day Nero, fiddling while our own Rome burned. This song has

little to do with jazz,

but everything to do with those "summer

feelings"---and I can think of fewer ways to express such feelings

than by celebrating

one of the most significant cultural gifts bestowed upon world music,

emergent from the African

American experience, and taking a distinctive form through the

blending of African and European idioms.

This was something I planned long before the events of the day. But before we

start the newest installment in our annual Summer Music Festival, on June 20th,

indulge those "summer

feelings": check out the original

studio recording of this song, the

official video, the Quarantine

Video Version, the Bassboosted

Remix, and the Nightcore

Whore Remix [YouTube links].

Posted by chris at 03:52 PM | Permalink |

Posted to Culture | Film

/ TV / Theater Review | Music

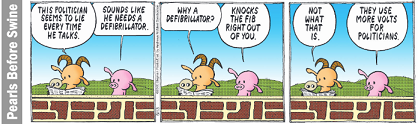

More Volts (Not Votes) For Politicians!

Another gem from the anarchic "Pearls

Before Swine" comic strip by Stephan

Pastis:

Posted by chris at 10:43 AM | Permalink |

Posted to Politics

(Theory, History, Now)

Lists, Lists, and More Lists

Back on May 5, 2020, I was first tagged by my friend Daniel Bastiat (on

Facebook) to engage in a book challenge: To post the covers of seven books over

a seven-day period that had an effect on you, with no explanation. I listed the

following seven books (and tagged other people with this, and subsequent

challenges):

1. "Dialectical

Investigations", by Bertell Ollman

2. "A

New History of Leviathan: Essays on the Rise of the American Corporate State",

edited by Ronald Radosh and Murray Rothbard

3. "Capitalism:

The Unknown Ideal", by Ayn Rand

4. "National

Economic Planning: What is Left?", by Don Lavoie

5. "The

Disowned Self", by Nathaniel Branden

6. "Nationalism

and Culture", by Rudolf Rocker

7. "The

Libertarian Alternative", edited by Tibor Machan.

This was followed by a ten-day "Album Challenge", posting key albums that

affected you throughout your life:

1. "Ben

Hur" (1959 soundtrack)

2. "Concierto

de Aranjuez" (Julian Bream)

3. "Concierto"

(Jim Hall)

4. "Intuition"

(Bill Evans)

5. "The

Mad Hatter" (Chick Corea)

6. "Thriller"

(Michael Jackson)

7. "Ultimate

Sinatra" (Frank Sinatra)

8. "At

the Close of a Century" (Stevie Wonder)

9. "I

Wanna Be Around" (Tony Bennett)

10. "Getz/Gilberto"

(Stan Getz/Joao Gilberto/Astrid Gilberto/Antonio Carlos Jobim)

And that was followed by the final challenge: List ten films and ten TV shows

that had an impact on your life or tastes or that loom large in your memory

(they need not even be ranked among your all-time "favorites", though clearly

they may very well be). So here were my choices for that challenge:

Day 1:

Film: "King

Kong" (1933)

TV: "Looney

Tunes Cartoons" (1930-1969)

Day 2:

Film: "The

Wizard of Oz" (1939)

TV: "The

Honeymooners" (1956)

Day 3:

Film: "North

By Northwest" (1959)

TV: "The

Twilight Zone" (1959)

Day 4:

Film: "Ben-Hur"

(1959)

TV: "The

Fugitive" (1963)

Day 5:

Film: "Inherit

the Wind" (1960)

TV: "I,

Claudius" (1976)

Day 6:

Film: "Planet

of the Apes" (1968)

TV: "Jesus

of Nazareth" (1977)

Day 7:

Film: "The

Exorcist" (1973)

TV: "The

Winds of War" / "War

and Remembrance" (1983/1989)

Day 8:

Film: "The

Godfather: The Complete Epic, 1901-1959" (1977)

TV: "The

X-Files" (1993)

Day 9:

Film: "The

Deer Hunter" (1978)

TV: "The

West Wing" (1999)

Day 10:

Film: "Alien"

(1979) / "Aliens"

(1986) - I know, it's cheating, but I can't pick one without the other!

TV: "24"

(2001)

And that's all folks! Next up will be the Fifth Annual Summer Music

Festival (Jazz Edition), which will begin when summer arrives in the Northern

hemisphere and conclude on the day of the autumnal equinox.

Posted by chris at 05:22 PM | Permalink |

Posted to Culture | Film

/ TV / Theater Review | Frivolity | Music | Remembrance

JARS: Our Twentieth Anniversary Celebration Begins!

I am delighted and deeply honored to announce the publication of the first of

two issues celebrating the twentieth anniversary of The

Journal of Ayn Rand Studies. Tonight, it made its debut on JSTOR;

print subscribers should expect the first of these two historic issues within

the next couple of weeks.

The following excerpt is from the Introduction I wrote to Volume 20, Number 1:

Welcome to the first issue of the twentieth anniversary volume of The Journal

of Ayn Rand Studies.

If someone had told me that I'd even be writing that introductory sentence

twenty-plus years ago, when the very first issue of the journal was in the

planning stages, I would never have believed it. But here we are, commencing our

celebration of the twentieth volume in our history with the first of two issues

that will feature reviews and discussions of works relevant to Rand studies that

have never been formally examined in our pages.

JARS began

as a fledgling independent periodical in Fall 1999, the brainchild of Liberty magazine

editor Bill Bradford (1947-2005). He enlisted Stephen Cox and me as founding

co-editors, with a founding advisory board of only three (Robert L. Campbell,

Mimi Reisel Gladstein, and Larry Sechrest). By our second issue, the advisory

board had expanded to include Douglas J. Den Uyl, Robert Hessen, John Hospers,

Lester H. Hunt, Eric Mack, and Douglas B. Rasmussen. With the passing of our

dear friends, Bill, John, and Larry, we expanded our Editorial Board to four

(Stephen Cox, Robert L. Campbell, Roderick T. Long, and me) and our Advisory

Board to a dozen (with the 2013 additions of David T. Beito, Peter J. Boettke,

Susan Love Brown, Hannes H. Gissurarson, Steven Horwitz, and David N. Mayer).

Sadly, David passed away on 23 November 2019; we dedicate this first issue of

our twentieth anniversary volume to his memory.

It should be noted, however, that our editors and advisors provide only a hint

of the astounding interdisciplinary character of the journal, which has

published essays in such fields as anthropology, economics, English and theater

arts, history, law, literature, philosophy, politics, and psychology. Starting

with the July 2013 issue, the journal began a new phase as a Pennsylvania State

University Press print-published periodical. Now we are indexed by nearly two

dozen abstracting services, are available to thousands of public, private,

not-for-profit, business, and institutional libraries worldwide, and are

published electronically by both JSTOR and Project MUSE. Our visibility and

accessibility have grown enormously, as has our subscription base. Our total

electronic downloads alone have gone from 7,922 in 2013 to 14,515 in 2019. I

expect a sharp jump in those figures with the debut of these two very special JARS issues.

We have published important symposia on remarkably diverse topics, including

Rand's aesthetics (Spring

2001), Rand and progressive rock (Fall

2003), Rand's literary and cultural impact (Fall

2004), Rand among the Austrians (Spring

2005), and Rand's ethics (Spring

2006). We brought out two issues celebrating our tenth anniversary,

including one devoted to Rand and Nietzsche (Spring

2009); a 2016

double issue (and our first published Kindle

edition) devoted to an examination of "Nathaniel Branden: His Work

and Legacy"; and a December

2019 issue marking the sixty-plus-year career of Atlas Shrugged.

With this thirty-ninth issue in our history, we will have published 366 articles

by 173 authors.

The introduction continues with a list of acknowledgments to all those who have

made this achievement possible. We remain the only double-blind

peer-reviewed interdisciplinary scholarly periodical published by a university

press devoted to the study of Ayn Rand and her times. I conclude my introduction

by acknowledging our most important debt:

In the end, however, we thank our readers above all, because they are the key to

our phenomenal success. Here's to another two decades and beyond of JARS triumphs

. . . two decades, or until such time as Rand studies have so penetrated the

literary and philosophic canon that specialized journals of this nature are no

longer required.

So... what do readers have in store for them in this twentieth anniversary

celebration? As mentioned above, we decided to devote two issues to reviewing

those works in the general area of Rand studies, which have never been

critically appraised in our pages. The list of works reviewed in this first

issue of volume 20 are:

Understanding Objectivism,

by Leonard Peikoff

How Bad Writing Destroyed the World: Ayn Rand and the Literary Origins of the

Financial Crisis,

by Adam Weiner

Perspectives on Ayn Rand's Contributions to Economic and Business Thought,

edited by Edward W. Younkins

Equal Is Unfair: America's Misguided Fight against Income Inequality,

by Don Watkins and Yaron Brook

Selfish Women,

by Lisa Downing

Ayn Rand and the Posthuman: The Mind-Made Future,

by Ben Murnane

A New Textbook of Americanism: The Politics of Ayn Rand,

edited by Jonathan Hoenig

Independent Judgment and Introspection: Fundamental Requirements of the Free

Society,

by Jerry Kirkpatrick

The Unconquered: With Another, Earlier Adaptation of "We the Living",

by Ayn Rand (edited by Robert Mayhew), and Ideal: The Novel and the Play,

by Ayn Rand

Who Is John Galt? A Navigational Guide to Ayn Rand's "Atlas Shrugged",

by Timothy Curry and Anthony Trifiletti, and So Who Is John Galt, Anyway? A

Reader's Guide to Ayn Rand's "Atlas Shrugged", by Robert Tracinski

Anthem,

by Ayn Rand (adapted by Jennifer Grossman and Dan Parsons, illustrated by Dan

Parsons); Anthem, by Ayn Rand (adapted by Charles Santino and Joe

Staton); The Age of Selfishness: Ayn Rand, Morality, and the Financial Crisis,

by Darryl Cunningham

What's in Your File Folder? Essays on the Nature and Logic of Propositions,

by Roger E. Bissell

***

As is the case with every issue, we have introduced at least one new contributor

to the JARS family. This issue brings debut pieces from Roger Donway and David

Gordon. Here is our Table of Contents for Volume 20, Number 1 (the abstracts can

be found here;

contributor biographies can be found here):

What Ayn Never Told Us - Dennis C. Hardin

How Bad Scholarship Destroys Literary and Economic Analysis - Peter J. Boettke

Promethean Commerce and Ayn's Alloy - Roger Donway

Misguided Arguments - David Gordon

Ayn Rand: Selfish Woman - Mimi Reisel Gladstein

Ayn Rand and Posthumanism - Troy Camplin

Textbook of Americanism 2.0 - Neil Parille

The Psycho-Epistemology of Freedom - Steven H. Shmurak

Posthumous Publications - Stephen Cox

Who John Galt Is - Roger E. Bissell

Illustrated Rand: Three Recent Graphic Novels - Aeon J. Skoble

File Folder Follies - Fred Seddon

Those seeking to subscribe to the journal should visit the sites linked here.

And---as we march into the third decade of this remarkable journal---those

wishing to submit manuscripts for consideration should follow the instructions here.

Once again: My eternal gratitude to every person who has made this day possible.

Posted by chris at 12:10 AM | Permalink |

Posted to Culture | Periodicals | Politics

(Theory, History, Now) | Rand

Studies

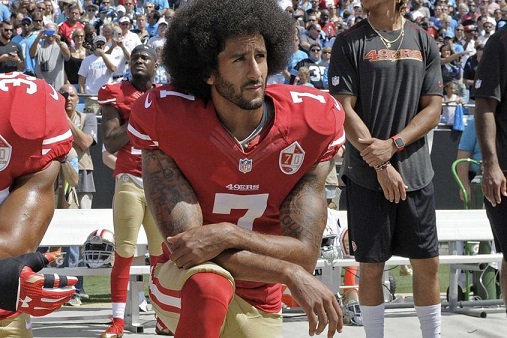

America: On Wounded Knee

When I started to compose this essay, I couldn't get three images out of my

mind. The first image is of former NFL quarterback, Colin

Rand Kaepernick, who took to kneeling during the national anthem, in

protest against police brutality and racial inequality in this country:

Some folks expressed great moral indignation at Kaepernick's "disrespectful"

behavior; Donald

Trump himself called on NFL owners to fire anyone who "disrespects

our flag." At the time, he said: "Get that son of a bitch off the field right

now, out, he's fired. He's fired! ... That's a total disrespect of our heritage.

That's a total disrespect of everything that we stand for." The NFL was so

petrified by the public outcry that it adopted a league policy, allowing teams

to fine any players who exhibited such behavior "an unspecified sum"---demanding

further that such players be relegated to the locker room rather than exhibit

disrespect for the flag on the field, for all to see. When all was said and

done, Kaepernick went unsigned after the 2016 season, and filed a grievance

against the NFL, accusing owners of colluding to keep him out of the league. He

later reached a confidential settlement with the league, and withdrew the

grievance.

Alas, the technicalities of NFL ownership of teams didn't make this a clear-cut

issue that might fall under free speech guidelines; players employed by the NFL

either play by the rules or get another job. The fact that most of them play in

stadiums that have been built with

taxpayer dollars or through the use of eminent

domain didn't mitigate the circumstances in favor of free expression.

Next to that image of an NFL player taking a knee during the national anthem,

and all the hoopla that surrounded it, there is the harrowing image of George

Floyd, an unarmed black man in Minneapolis, Minnesota, handcuffed,

face down, pinned to the ground by a white policeman, Derek Chauvin, whose knee

was also bent---grinding into the back of Floyd's neck, even as he pleaded with

Chauvin that he couldn't breathe, that he was going to die.

Fortunately, the moral outcry over this nightmarish injustice seems to have

eclipsed the umbrage expressed by so many when they saw an NFL player kneeling

during "The

Star-Spangled Banner"---in protest of police brutality.

But there is now a third image that haunts me. It is the image of another man,

George Floyd's brother Terence, who traveled from Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn,

to the spot in Minneapolis, where his brother was killed. Terence tried to

kneel, but the wounds in his soul ran so deep, that they crippled his ability to

balance himself. He collapsed in tears.

These three images tell different stories---but they are all united in some way.

They tell the story of protest---both after and before, before and after, the

ongoing murder of unarmed black men throughout our country by police officers.

They tell the story of what happens when taking a knee in prayer morphs into

using a knee as a weapon to snuff out the life of another human being. They tell

the story of what happens in the aftermath of that death, when a kneeling man

can barely steady himself in an effort to pay tribute to his fallen brother.

America is now under siege, not by rioters, but by what these three images

project: protest, death, and remembrance. And if what we are seeing on the

streets of America is a war of sorts, I can only quote Herman Wouk: "The

beginning of the end of war lies in remembrance."

***

Over these last three months, I have lived in a home town that has lost nearly

30,000 human beings to a pandemic. I've posted twenty-six

installments on the Coronavirus.

It is typical of funeral

processions around these parts for the hearse carrying a person's

remains to pass that person's home on the way to the cemetery. So, every

morning, over the past few months, as I get on my stationary bike to work out in

the front room of my home, I look out the bay window of my apartment, which

faces the street below, and I've seen---day-in, day-out---one funeral procession

after another. A part of you becomes numb to the vision. Until it doesn't.

The morning after Memorial Day, I heard of yet another nightmarish tragedy

taking place in an American city. It was the day after George

Floyd was killed on the streets of Minneapolis, Minnesota by police officer

Derek Chauvin, whose knee was pinned to the right side of Floyd's

neck for 8

minutes, 46 seconds, even as the

victim pleaded that he could not breathe---and onlookers screamed for the

officer to stop [warning: graphic YouTube link].

When I first heard this news report, I found myself just as numb. Numb not

because it was yet another death in a time of unending mass death, devastation,

and destruction. Numb because it was the death of one more African American man,

in a long list of such atrocities, by a police officer. These senseless

brutalities have become so common over the years. But the outrage expressed in

their aftermath has become so predictable---and so ineffective---that as I

watched the news, all my overtaxed brain could manufacture as a response was:

"Another one."

I shook my head in despair, I felt my eyes well up with tears, but I was

confident that, once again, people would express their anger for a few days, the

politicians would get in their potshots at each other, as they did in the

aftermath of Charlottesville, and life would return to "normal"---whatever the

hell that term means nowadays.

But I was wrong. By Friday night, May 29th, the

protests were spreading from coast-to-coast. And when I turned on the

television at around 11 pm, and saw the streets of my home town, Brooklyn,

aflame, in front of the Barclays Center, and down Flatbush Avenue, I could not

contain the depths of my sorrow. I just began to cry. Night after night, I have

watched peaceful protests punctuated by violence and looting, with the typical

push-back from police.

I'm not going to sit here and pontificate about how violence is not the answer.

For a person who has celebrated the riotous response of the Stonewall

Rebellion fifty-one years ago, I certainly appreciate how a violent

reaction against a corrupt police force attempting to destroy the lives,

liberties, and property of a marginalized group can have a revolutionary effect.

Those rebellious souls in 1969 directed their anger specifically at a corrupt

police force that routinely raided the Stonewall Inn and arrested its peaceful

patrons to clamp down on "lewd behavior" (that is, same-sex folks who were

holding hands and kissing in the confines of a private establishment). Those

raids were almost predictable---especially

if the police didn't get their timely payola from the Mafia owners of the bar.

This singular violent event has been marked ever since that fateful late

June day not with further violence, but with annual parades, in which

police---some of them out and about, walk arm-in-arm with their same-sex

partners and friends.

The current violence that has punctuated otherwise peaceful mass protests across

the country might be chalked up to spontaneous outbursts from those who feel the

sting of poverty

and institutional inequality, magnified further in the

wake of lockdowns and high unemployment during a period in which a pandemic has

taken the lives of over 100,000 Americans (many of them Latino and

African American, in percentages disproportionate to their populations).

In many instances, the violence, however, has not been spontaneous at all, since

it does appear that outside groups have infiltrated these protests specifically

to cause mayhem---provocateurs

from the left or the

right, perhaps. The looting of a

Target store in Minneapolis, known for its

collaboration with the police, might seem justified to some. But mob

action sustained over these many days must, by necessity, degenerate over time.

It is not about striking a blow for equality or against oppression; it is not

about looting

luxury stores in midtown Manhattan or Macy's

on 34th Street or the

swanky shopping districts in SoHo [YouTube links] as a symbol against

"excess"

[Twitter link]. The mob does not distinguish; it ultimately aims its wrath even at

small neighborhood businesses and stores like those along the Grand Concourse in

the Bronx [YouTube link], which directly impact the

very communities that have been victimized by police brutality. Their

store owners have struggled to keep afloat throughout this pandemic, and now

they have no businesses left to open.

Terence Floyd,

George's brother, who traveled from Brooklyn to pray at the site in Minneapolis

where George was murdered, collapsed in agonizing grief when he arrived there.

You could hear him praying---"I need you and Pops to watch over me"---as he

cried uncontrollably.

But then he turned to the crowd: "I understand ya'll upset. But ... I doubt

y'all are half as upset as I am. So if I'm not over here wilding out, if I'm not

over here blowing up stuff, if I'm not over here messing up my community---then

what are y'all doing!? What are y'all doing? Y'all doing nothing! Because that's

not gonna bring my brother back at all. ... You all protest, you all destroy

stuff. And they [the powers that be] don't move. You know why they don't move?

Because it's not their stuff. It's our stuff. They want us to destroy our

stuff." He implored them to find "another way." "My family is a peaceful

family," he exclaimed. He asked the protesters to use their anger as a tool for

peaceful, nonviolent change. He urged them to exercise their power at the ballot

box and implored them to an even higher cause: "Educate yourself," he said.

"It's a lot of us. And we still gonna do this peacefully."

This has been a mantra among long-time civil rights advocates. Even Al

Sharpton, an "imperfect

vessel" if ever there was one, has also expressed an urgent moral

indignation: "Don't use George Floyd and Eric Garner as props," he declared.

"Activists go for causes and justice, not for designer shoes. New York should

set the tone, because the first time we heard, 'I can't breathe,' it was not in

Minneapolis. It was on Staten Island, six years ago, and we did nothing."

I have always understood the horrific structural issues at work, the broader, tragic context of historic and systemic brutality that breeds violent responses such as we've seen over the past week. I have addressed these issues countless times over the past three decades, including essays, in recent years, on subjects as varied as the war on drugs and the problems of mass incarceration, the trouble with Trump and Antifa, and the reciprocal relationship between the growth of state power and racism as a cultural and political phenomenon. I refer readers to those highlighted links because this is just not the time to say: "I Told You So." [Ed.: See also this essay on Cato Unbound.]

Nevertheless, understanding why violence often punctuates protests does

not mean that I subscribe to the view that nonviolent resistance is somehow

deficient or protective

of the status quo.

For a person, like me, who has dedicated his life to exploring the context of

human freedom, who has upheld the libertarian ideal of a free society, the

status quo is a system that is the embodiment of violent brutalization. Violence

is a way of life in this country. It is the means by which a genuinely political economy

redistributes wealth to those who are powerful enough to wield the mechanisms of

state. They have been wielding those mechanisms at home and abroad for eons,

especially through the apparatuses of "national security," designed to sustain a

policy of "perpetual war for perpetual peace." It sometimes astonishes me that

so many folks who are understandably threatened by these newest displays of

violence on the streets of America's cities and who call upon their government

to "dominate" the rioters, have rarely given thought to how such "domination"

has given the United States the dubious distinction of having the

highest incarceration rate in the entire world---higher than both

China and Russia, and the even more horrific distinction of being, historically,

among the most powerful forces for instability throughout the globe, given

sustained policies of interventionism abroad.

On the importance of using strategies of nonviolent resistance---not to

be confused with pacifism---I highly recommend the work of Gene

Sharp, a man of integrity whom I met and with whom I had a 25-year

correspondence. The author of such books as From

Dictatorship to Democracy: A Conceptual Framework for Liberation, Social

Power and Political Freedom and a three-volume work, The

Politics of Nonviolent Action, Sharp did more to champion various

strategies by which to overturn the status quo in ways that tend not to

reproduce the patterns of brutality that its practitioners seek to end.

Over this past week, there have been remarkable displays of how nonviolent

protest---in some profoundly symbolic gestures---can change the dynamics between

protesters and those to whom their protests are typically directed. Yes, we have

seen burning neighborhoods, but we have also heard stories and seen images

marked by an extraordinary depth of humanity. From Bellevue,

Washington, where the Police Chief declared "We are with you. We are

not against you"---to Miami,

Florida [YouTube links], where a highway trooper hugged a protester,

who told him "I love you"... from Foley Square in Manhattan, where police

officers kneeled to the applause of the protesters, a young African

American man reaching out, telling them: "I really appreciate you doing that.

Thank you very much. I hope you all stay safe and have a great night" to images

of protesters

in Louisville, Kentucky forming a human barrier to protect a police officer who

had been separated from his unit, from violent attack. White

women standing in a line, to separate and protect protesters from police and

police from protesters. Police chiefs from New Jersey to Wisconsin

walking side-by-side with protesters. Chief

of Department of the New York City Police, Terence

Monahan, hugging an activist as protesters paused in Washington

Square Park, the same park where I once protested myself---against

the reinstatement of selective service registration for the draft by President

Jimmy Carter---telling protesters that he was with them standing

against police brutality.

And then there was an unforgettable

video that went viral [YouTube link] of Flint

Michigan, Genesee county sheriff Chris Swanson [YouTube link], who

confronted a gathering of protesters and spoke to them from his heart. He

assured the crowd that he meant them no harm. He took off his riot gear, put

down his baton, and yelled out to the crowd: "We want to be with you all

--- I

want to make this a parade, not a protest. ... These cops love you." The crowd

chanted: "Walk with us!" And he did. "We will protect you. We are with you," he

said. Later, he observed: "I knew that the benefit far outweighed the risk. And

when you show action of, listen: I'm going to make myself vulnerable in order to

come into your circle and show you that I want to be that solution. That was the

change maker right there. It was beautiful. Not a single arrest. Not a single

injury. Not a single fire."

As much as these stories and images uplift and inspire, Kumbaya is not going to

cut it. (Indeed, in

some instances, the same police who knelt with the protesters were

later involved in tear-gassing the folks with whom they expressed solidarity.)

Nor is the opposite tendency among those who simply call for the outright

abolition of the police going to cut it. Why stop there? Abolish the state!

To my principled anarchist friends (not the "bomb-throwing" kind),** who see the

state and its police functions as the distillation of evil in the modern world,

I am compelled to ask: If you were capable of "pushing the button," what do you

propose to replace it with? This is the danger of thinking undialectically,

of dropping the context of the conditions that exist in the real world. We are

dealing with structural racism that permeates not only our political

institutions but our very culture. Certain measures can be taken (from

ending qualified

immunity to challenging the

militarization of the police force) but a genuine cultural transformation

is a necessary precondition for any genuinely radical social and political

change.

***

Despite all these mixed messages in an age of mixed premises, I must end this

essay where it began---with images. Images of many police officers who have now

taken to one knee, one wounded knee, the position of the Colin

Kaepernicks of this world---in opposition to the brutality in their own ranks

and the racial inequality it perpetuates. [Ed.: This practice has continued in

earnest even weeks after the riots have subsided... to the credit of people on

both sides of a crumbling blue wall.]

--

Notes

** In a recent study group discussion for the anthology, The

Dialectics of Liberty, I had the occasion to quote from a Spring

1980 article I wrote, while an undergraduate at New York University for The

New Spectator: The NYU Journal of Politics:

Anarchism has had a long and negative conceptual history. Traditionally, the

image of the anarchist has always been one of a bearded, bomb-hurling immigrant

attempting to violently overthrow the social order in a revolutionary and bloody

battle against authority. It is quite ironic that skeptics will see anarchism as

a ridiculous, idealistic, floating abstraction without realizing that the

present-day situation is in essence, one of international anarchy among monopoly

governments, which have considerably refined the practice of bomb-throwing

beyond what any anarchist would have dreamed. In this context, the real issue

seems to be what kind of "anarchy" we want---governmental or voluntary.

Posted by chris at 11:19 PM | Permalink |

Posted to Culture | Dialectics | Foreign

Policy | Politics

(Theory, History, Now) | Remembrance | Sports