NOTABLOG

MONTHLY ARCHIVES: 2002 - 2020

| OCTOBER 2017 | DECEMBER 2017 |

The Russian Connection: Rand versus Kant

There has been a debate raging on Facebook about Rand's antipathy to Kant as the

most "evil" man in the history of philosophy. I certainly am not a Kantian, but

let's just say that while Rand often gets some things right in her view of the

history of philosophy, she often made sweeping generalizations that were at

best, uncharitable, in her evaluation of various thinkers. "Uncharitable" is

partially an outgrowth of a not-very-sophisticated treatment of certain thinkers

(Hegel and Marx come to mind), especially in the title essay to her book For

the New Intellectual.

In the meanwhile, some folks have wondered when Rand developed this rabid

antipathy to Kant. For example, in the 1936 version of We the Living,

Rand has the character Leo quoting Kant and Nietzsche at social gatherings. In

the 1959 version, Rand airbrushed Kant from the text, substituting Spinoza for

Kant in Leo's comments. This flies in the face of Rand's own view that she had

made various changes to the second edition of her first novel, which were

stylistic in nature. Clearly, some changes were made that were of a more

substantive character, and I discuss these in Chapter Five of my book, Ayn

Rand: The Russian Radical.

In that chapter, I state the following:

Yet in my view, it is far more likely that Rand's anti-Kantianism was an

outgrowth of her exposure to Russian thought, rather than with any possible

acquaintance with Schopenhauer's view [a suggestion made by George Walsh in a

JARS essay that is critical of Rand's views of Kant]. Whereas Schopenhauer

celebrated the Kantian metaphysical distinctions, most Russian philosophers

rejected Kant because they believed that he had detached the mind from reality.

As I suggest, such thinkers as Solovyov, Chicherin, and Lossky were aiming for

an integration of the traditional dichotomies perpetuated by Kant's metaphysics.

Chicherin, for instance, argued that in Kant's system, pure concepts of reason

are empty, and experience is blind. Kant's view makes "metaphysics without

experience . . . empty, and experience without metaphysics blind: in the first

case we have the form without content, and in the second case, the content

without understanding" [quoted by Lossky in his History of Russian Philosophy].

Interestingly, Rand's own view of the rationalist-empiricist distinction, and of

Kant's critical philosophy, is deeply reminiscent of Chicherin's parody. For

Rand, rationalists had embraced concepts divorced from reality, whereas

empiricists had "clung to reality, by abandoning their mind" (New

Intellectual, 30). Kant's attempt to transcend this dichotomy failed

miserably because his philosophy formalized the conflict. Rand writes: "His

argument, in essence, ran as follows: man is limited to a consciousness of a

specific nature, which perceives by specific means and not others, therefore,

his consciousness is not valid; man is blind, because he has eyes---deaf,

because he has ears---deluded, because he has a mind---and the things he

perceives do not exist, because he perceives them" (39).

Rand's teacher, Lossky, was the chief Russian translator of Kant's works. He too

had criticized Kant's contention that true being (things-in-themselves)

transcends consciousness and remains forever unknowable. Lossky sought to defend

the realist proposition that people could know true reality through an

epistemological coordination of subject and object. In this process, the real

existents and objects of the world are subjected to a cognitive activity that is

metaphysically passive and noncreative. Lossky rejected Kant's belief that the

mind imposes structures on reality. Such Kantian subjectivism subordinates

reality to knowledge, or existence to consciousness. It resolves phenomena in

subjective processes that are detached from the real world and distortive of

objective reality [from Lossky's book, The Intuitive Basis of Knowledge].

Furthermore, Lossky criticized Kant for invalidating metaphysics as a science.

Since Kant held that the mind perceives things not as they are but "as they seem

to me," he institutionalized a war not only on metaphysics, but on the very

ability of the mind to grasp the nature of reality. Though there is no evidence

that Rand studied Kant formally while at the university, it is conceivable that

her earliest exposure to Kant's ideas occurred in her encounters with the

celebrated Lossky. Her distinguished teacher was among the foremost Russian

scholars of German philosophy. Lossky's rejection of Kantianism was essential to

his ideal-realist project. It is entirely possible that Rand absorbed

inadvertently a Russian bias against Kant.

As I point out in my Facebook post:

To my knowledge, it's not that Kant was not being taught in the university; it's

that whatever Kantian philosophy that was taught, was typically critical. And

yet, there was a vibrant school of neo-Kantianism in Silver Age Russia, the time

during which Rand came to intellectual maturity. The leading exponent of

neo-Kantianism in Russia was Aleksandr Vvedensky, whom I've pegged as one of

Rand's teachers at the University of Petrograd (the most likely teacher of the

course on "Logic"). Interestingly, Shoshana Milgram states that it was Vvedensky

who was the teacher of the course on ancient philosophy that Rand took, rather

than N. O. Lossky, whom I identified as the teacher---in league with Rand's

recollections. I have a forthcoming essay on this subject and other subjects in

the December 2017 issue of The

Journal of Ayn Rand Studies. I think the bulk of the evidence

comes down on the side of Rand's recollections.

Interestingly, Lossky (who had translated into Russian Kant's Critique of

Pure Reason as well as the famous Paulsen monograph on Kant, which Rand

referenced) tells us that Vvedensky's neo-Kantianism was reflected in all his

books and in his courses, especially. (So I find it odd that Milgram refers to

Vvedensky as a "famous Platonist" when, in fact, he was a famous neo-Kantian,

whose teachings reflected the neo-Kantian take on the history of philosophy).

Lossky was famously anti-Kantian, but I have more to say in the forthcoming

essay.

I was asked by Anoop Verma about the main points of difference between Russian

neo-Kantianism and neo-Kantianism in the West. This requires a much longer

answer than I'm capable of providing in this space, but V. V. Zenkovsky argues

in his two-volume work, A History of Russian Philosophy, that the

neo-Kantian tendencies, especially those found in the works of its leading

representative, A. I. Vvedensky, do not break with the central Kantian ideas,

except that these ideas are related to "the root problems of the Russian

spirit," adding that one finds "echoes of a familiar 'panmoralism'" in the

Russian neo-Kantian vision. Zenkovsky argues further that the Russian version

tends to approach "critical positivism" and even "pure positivism." I know this

is not satisfying as an answer, but I want to recommend Zenkovsky's treatment of

"Neo-Kantianism in Russia" (chapter 13 of his aforementioned book).

Lastly, I just want to touch upon a point made by Robert Mayhew, who compares

the 1936 version of We the Living and the 1959 version of that book, in a

chapter of his edited anthology Essays on Ayn Rand's "We the Living". As

I mentioned, Rand claimed to have made "editorial changes" in the book's

reissued 1959 version, that were stylistic and grammatical, given that her

writing at the time was a reflection of "the transitional state of a mind

thinking no longer in Russian, but not yet fully in English." She claims to have

eliminated some "awkward or confusing lapses" and "a few paragraphs that were

repetitious or so confusing in their implications that to clarify them would

have necessitated lengthy additions. In brief, all the changes are merely

editorial line-changes. The novel remains what and as it was," she claims.

Clearly that is not the case, as I have documented in my comparison of both

versions of the novel in Ayn Rand: The Russian Radical. One can find that

comparison in "A 'Nietzschean' Phase?", which is a sub-section of Chapter Four

in the second edition of the book. I think though a Nietzschean element remains

within Rand throughout her entire corpus, the more belligerent Nietzschean

elements that she repudiated, are more visible in the 1936 version, as readers

will see in my comparative analysis.

Now Mayhew claims that Rand could not have possibly gotten her view of Kant from

her Russian period because in the 1936 version, the character Leo spouts Kantian

phrases at social gatherings; Rand replaces any reference to Kant in the 1959

version, substituting Spinoza instead. I think that Rand's anti-Kantianism

became more pronounced by the late 1950s and early 1960s as a result of her

exposure to some of the views of such folks as Isabel Paterson, and her own

students, Leonard Peikoff and Barbara Branden, both of whom studied under Sidney

Hook at New York University.

And yet, I do find it ironic that Rand uses Paulsen's interpretation of Kant,

found in his 1898 book, Immanuel Kant: His Life and Doctrine, which was

translated into Russian by Rand's philosophy professor N. O. Lossky. I don't

know if Rand read the Paulsen book in its Russian translation originally, but

her discussion of that book as so revealing of Kant's malevolence, can be found

in an October 1975 essay, "From the Horse's Mouth" (first published in The

Ayn Rand Letter, and later in Philosophy: Who Needs It). And even her

remark that Kant condemned humanity to being "blind" because he has eyes echoes

the Russian anti-Kantian view of Chicherin, who uses the same "blind" metaphor.

So, even if Rand didn't necessarily get her anti-Kantian bias from her Russian

studies, she seems to have come full circle by embracing a view so prevalent in

the Russia of her youth.

Postscript:

Kirsti Minsaas asked for examples of Leo quoting Kant in the original 1936

edition of We the Living. I responded:

Kirsti, I don't have my 1936 reproduction accessible, but what Mayhew writes in

his essay "We the Living: '36 & '59" in his edited anthology "Essays on Ayn

Rand's 'We the Living'" is accurate (to my recollection); he writes:

"The most interesting name change comes in the passage describing the young Leo.

One line in the original reads: 'When his young friends related, in whispers,

the latest French stories, Leo quoted Kant and Nietzsche.'

"In the '59 edition, 'Kant' is changed to 'Spinoza'. Rand had a mild respect for

Spinoza's egoism; but more important, in her mature philosophical writings she

makes it clear that she regards Kant as the most evil philosopher in history, a

view she did not hold in Russia or when she first got to the United States.

(Later in the novel, when Leo is arrested, the '36 edition has him uttering an

arguably Kantian line to Andrei: 'A tendency for transcendental thinking is apt

to obscure our perception of reality'. The line was cut.")

It really is fascinating to compare the two editions. Someday, someone out there

should publish a "Scholar's Edition" (much as they do at the Mises Institute),

which includes both the 1936 and the 1959 versions. But I won't hold my breath.

Posted by chris at 12:47 AM | Permalink |

Posted to Rand

Studies

Song of the Day #1519

Song

of the Day: It's

a Charlie Brown Thanksgiving ("Thanksgiving Theme") [YouTube link],

music composed and performed by the Vince

Guaraldi Trio for this 1973

animated feature, is one of those recognizable jazz themes long

associated with all things "Peanuts." Thanksgiving is

often viewed as the kick-off to the holiday

season (though nowadays, stores seem to be putting up holiday

decorations before Labor Day!). Despite much

heartache over the past year, I never fail to count the many

blessings for which I am thankful---loving family and friends, warm memories,

passionate work, the wonderful food on this holiday that only a loving home can

provide--and, of course, the sweetness of all the music I have celebrated in "My

Favorite Songs." A Happy

Thanksgiving to All!

Posted by chris at 08:13 AM | Permalink |

Posted to Music | Remembrance

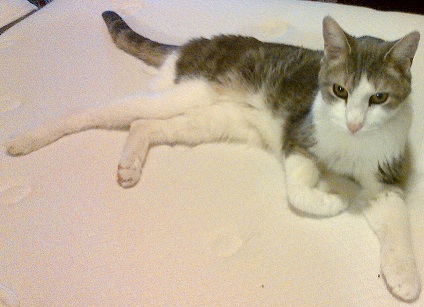

Our Little Dante Crosses the Rainbow Bridge

After the loss of two of my dearest friends over the last five months, Murray

Franck and Michael

Southern, I didn't think I had much of a heart left to break.

It turns out my heart is much larger with an almost infinite capacity to

love---and to grieve. This morning, we lost our little Dante (April 29, 2000 -

November 11, 2017). He had a life full of love, fun, food, travel, and TV. But

this morning, the Rainbow Bridge beckoned.

Only folks who have had pets will understand the grief of losing a beloved

member of the family, especially one who has brought such joy to our lives. We

will miss him and love him, and keep him in our memories eternally. I love you,

my little Dante.

Postscript (13 November 2017): I wanted to thank everybody who has

responded to me privately and publicly (on Facebook) during a period of immense

personal grief. I have no doubt that some of this grief is cumulative, given

recent losses in my life, as noted above. But only pet people understand the

uniqueness of the relationship between a person and a pet.

That unique character was noted by psychologist Nathaniel

Branden back in the 1960s, who enunciated what he called the "Muttnik

principle" in his exploration of the nature of psychological

visibility. His remarks were specifically about the relationship he enjoyed with

his dog Muttnik, but the principle is just as applicable to cats and other pets,

as it is to dogs, despite the differences that one sees among the species.

I've been fortunate enough to be both a "cat person" and a "dog person"; my

first experiences with pets were as a child with both cats (Peppers) and dogs

(Timmy), and later, with our cat Buttons (1969-1987), who lived to the ripe old

age of 18, and who was best friends with my brother and sister-in-law's dog,

Shannon. Buttons was followed, famously on Notablog, by our dog Blondie, who

passed away in 2006, at the age of 16.

Dante lived for 17-and-a-half years, and came to us through a dear friend not

too long after Blondie's death. When he arrived here, he immediately asserted

himself as King of the Castle, as Ralph

Kramden would say [YouTube link]. In many ways, he was the most

intelligent pet I've ever known. He'd watch television with remarkable

intensity, as if he were absorbing the unfolding plot of a story. If an image

came on the tube that he didn't like or some dissonant chords were heard in the

background of a film score, indicating a coming doom, he'd give definition to

the phrase "Scaredy

Cat," and high-tail

it outta here. He provided more laughs, more love, and more memories

than we'd thought possible, especially after the difficulty of losing our

beloved dog Blondie. Blondie had sat on my lap during the authorship of my

entire "Dialectics and Liberty Trilogy"---so much so that she was among those to

whom I dedicated the last book of my trilogy, Total

Freedom: Toward a Dialectical Libertarianism.

It is often said that there are essential differences between dogs and cats; an

old quip reminds us that dogs have families, while cats have staff. But despite

their apparent species-defined differences, each offers us something of great

value, as author William Jordan discusses in his book, A

Cat Named Darwin: How a Stray Cat Changed a Man into a Human Being.

In a sense, Dante picked up right where Blondie had left off. But this was not a

simple replacement; each offered something unique in terms of their individual

personalities and species-distinct behavior. Each was demanding, but the ways in

which they manifested that characteristic were as different as night and day;

where Blondie would jump and bark and lick you to death, Dante would simply

continue to meow until he was noticed, and if he was not noticed, he'd make his

presence known immediately. Typing on my laptop and therefore not focused

specifically on Dante? Not acceptable, as he'd walk across the keys demanding

attention. Eating? Not acceptable, as he'd jump on the table if we didn't at

least give him his own seat (his own chair, of course, fully cushioned and on

wheels). An Alpha Cat for an Alpha Household. What a perfect match.

And yet today, as I finally drag myself back to the laptop to continue working

on my various projects, I find myself typing without Dante by my side or on my

keyboard. This is new territory for me. There is an emptiness in this house, and

in our hearts, that is hard to communicate. I have found some comfort in the

work of Dr.

Wallace Sife, a long-time family friend and author of The

Loss of a Pet: A Guide to Coping with the Grieving Process When a Pet Dies.

But the depth of my grief is palpable.

Dante was a special cat; he was on thyroid medication for years, and we'd taken

good care of him---definitely giving him much more time on this earth than he

would have otherwise enjoyed (thanks to the loving care he received from Dr.

Linda Jacobson and her team). It made his swift degeneration over the

last few days of his life that much more painful. And yet, while it came at the

price of profound shock, King of the Castle that he was, Dante spared us the

necessity of having to make any life-and-death decisions on his behalf. Seeing

him degenerate and prepare for his own death is too painful to articulate; and

yet, there was something dignified in the way that nature took its course.

I will find a way to get through this. Keeping Dante, and all of my beloved

pets, alive in my memory, in photos and videos too, remains a comfort. But the

emptiness is going to be with me for a long time. And it is not something that

is easily filled by just getting another pet, as if they are interchangeable

units of the same stock. As with all things, grieving is a process only helped

by the passage of time.

Once again, my deepest appreciation to all of those who have expressed their

condolences to me.

Much love from Brooklyn, New York, to all of you,

Chris

Posted by chris at 12:50 PM | Permalink |

Posted to Remembrance

Russian Radical 2.0: Skeen Review and Forthcoming JARS Essay

I previously mentioned here at

Notablog that Ilene Skeen had reviewed the second edition of Ayn

Rand: The Russian Radical. Skeen has now posted a version of that

review on the blog "The Moral Case: For and Against." The review, entitled

"Objectivism in Context" appears here.

I should mention that my own essay, "Reply to the Critics of Russian Radical 2.0:

The Dialectical Rand," will be published in the December 2017 issue of The

Journal of Ayn Rand Studies, along with a companion reply from

Roger Bissell, entitled "Reply to the Critics of Russian Radical 2.0:

Defining Issues."

My article does not address Skeen's specific review, since it went to press

prior to the appearance of the Skeen essay. However, it does address most of the

central issues that Skeen raises.

I should mention, in passing, that aside from writing prefaces and introductions

to special issues of the journal, I have spent the last twelve years editing

essays written by others. Not that there's anything wrong with that; I embrace

the role I've played as a founding co-editor of the journal with open arms!

But literally, I have not published a single bona fide scholarly

contribution to the journal since the Fall 2005 issue, which included my essay,

"The Rand Transcript, Revisited." That essay later became Appendix II of the

second edition of Russian Radical. Well, as one can imagine, I really do

have a lot to say in the new essay, about the historical and methodological

theses of my book on Rand. It is an essay that, in my humble opinion, is a

definitive addition to the scholarly literature on Rand, because it not only

engages critics of the second edition (including such critics as Wendy McElroy,

who wrote a review of the second edition for JARS that appeared in the July 2015

issue; and two critics whose commentary on my work appears in the Blackwell Companion

to Ayn Rand), but enhances my own historical and methodological interpretive

work on Rand with some significant new research.

Having just signed off on the second corrected page proofs of the December 2017

issue, I can tell readers that the year-end edition contains many provocative

essays. Watch this space for more information on the forthcoming JARS. And

thanks again to Ilene Skeen for adding the review to "The Moral Case" blog!

Posted by chris at 08:55 PM | Permalink | Posted to Dialectics | Periodicals | Rand Studies