But powerfully symbolic images such as these have a surface appeal that obscures a much more complex reality. Too much Objectivist commentary on that reality has become a mere apologia for neoconservative folly. At risk is the abandonment of Ayn Rand's radical legacy.

The Current Crisis

Over the last few months, I have aired my views about the war in Iraq throughout cyberspace (see the various links posted to my Notablog. To be clear, there has never been a time where I doubted the immorality of a regime that fed its dissident citizens feet-first into wood chippers and industrial plastic shredders. I never doubted the rightness of striking back against those who initiate force or striking preemptively or unilaterally against imminent threats to American security-whatever the objections voiced by members of that morally bankrupt organization known as the United Nations. While I questioned the wisdom and timing of the Iraq war, the imminence of the Hussein threat, and the alleged links between Hussein's secularist Pan-Arabist Ba'ath Party and Bin Laden's fundamentalist Al Qaeda, my overwhelming concern was-and remains-the aftermath of the incursion.

I have strongly supported the attempt to bring to justice the fugitives of 9/11-the murderous Al Qaeda-or "to bring justice to them," as President Bush has said. I think this is an unconventional war requiring unconventional warfare, including ongoing disruption of terrorist finance, weapons, and communications networks. But I remain wary of any long-term U.S. expansion into the region. And I believe that a projected U.S. occupation of Iraq to bring about "democratic" regime change would not be comparable to the German and Japanese models of the post-World War II era.

Iraq is a makeshift by-product of British colonialism, constructed at Versailles in 1920 out of three former Ottoman provinces; its notorious internal political divisions are mirrored by tribal warfare among Shiites, Sunnis, Kurds, and others. By contrast, both Germany and Japan possessed relatively homogeneous cultures and the rudiments of a democratic past, while retaining no allies after the war. And in the case of Japan, the U.S. had the full cooperation of Emperor Hirohito, who stepped down from his position as national deity, to become the figurative head of a constitutional monarchy.

For those of us bred on Ayn Rand's insight that politics is only a consequence of a larger philosophical and cultural cause-that culture, in effect, trumps politics-the idea that it is possible to construct a political solution in a culture that does not value procedural democracy, free institutions, or the notion of individual responsibility is a delusion. Witness contemporary Russia, where the death of communism has given birth to a society of warring post-Soviet mafiosi, leading some to yearn for the good ol' days of Stalin. Clearly, "regime change" is not enough. But even if procedural democracy were to come to Iraq, it may be no less despotic than the brutal dictatorship it usurps, for majority rule without protection of individual rights is no check on the political growth of Islamic fundamentalism.

The lunacy of nation-building and of imposed political settlements-which have been tried over and over again in the Middle East with no long-term success-does not mean that there is no hope for the Arab world. Former Reagan administration advisor Michael Ledeen (The Intellectual Activist [TIA], January 2003) speaks of a rising revolt against theocracy in Iran, for example, among a younger generation that is fed up with their oppressive government. They eat American foods, wear American jeans, and watch American TV shows. I don't see how a U.S. occupation in any part of the region will nourish this kind of revolt. If anything, the United States may be perceived as a new colonial administrator. Such a perception may only give impetus to the theocrats who may seek to preserve their rule by deflecting the dissatisfaction in their midst toward the "infidel occupiers." I can think of no better ad campaign for the recruitment of future Islamic terrorists.

Even though I support relentless surgical strikes against terrorists posing an imminent threat to the United States, I have argued that America's only practical long-term course of action is strategic disengagement from the region. In the long-run, I stand with those American Founding Fathers who advocated free trade with all, entangling political alliances with none. If that advice was good for a simpler world, it is even more appropriate for a world of immense complexity, in which no one power can control for all the myriad unintended consequences of human action. The central planners of socialism learned this lesson some time ago; the central planners of a projected U.S. colonialism have yet to learn it.

A Deeper Cause

"Armies are in motion," observes Paul Berman, "but are the philosophers and religious leaders, the liberal thinkers, likewise in motion? There is something to worry about here," Berman continues, "an aspect of the war that liberal society seems to have trouble understanding-one more worry, on top of all the others, and possibly the greatest worry of all" ("The Philosopher of Islamic Terror," NY Times Magazine, 23 March 2003).

That worry is deeply philosophical-and one that cannot be ignored. There is a profound antipathy between Islamic fundamentalism and Western values, an antipathy that lies at the root of their mutual cultural alienation. But it took centuries to secularize the Western mind, and it is liable to take generations to accomplish a modicum of cultural change among Islamic nations. Berman provides one indication of the obstacles that lie ahead. He focuses on the philosophical forefather of Al Qaeda: Sayyid Qutb, who violently opposed the secular, socialist Pan-Arabist regime of the Egyptian dictator, Gamal Abdel Nasser. As a member of the fundamentalist Muslim Brotherhood, Qutb was executed in 1966. But his poisonous legacy lives on.

Qutb's progeny, Bin Laden, stands at one end of the Islamic spectrum, while Hussein's Ba'ath Party, the most violent Pan-Arabist successor, stood at the other. That Bin Laden sees Hussein as an immoral "infidel" is an extension of a fundamentalist credo, which repudiates "Zionists" and "Christian" Westerners from without, and secularists from within, the Muslim world. The fundamentalists want to marginalize or destroy not only the Pan Arabists, but also any "liberal" Muslims-who are viewed as no better than the pre-Islamic pagans of the Arabian peninsula. This is quite typical: Fundamentalists of any sort always begin by attacking the "impure" among their own faithful.

Pining for a theocratic Islamic caliphate, Qutb's influential "theological criticism of modern life" lamented the dualistic "schizophrenia" of the secular and the sacred, science and religion. But as is typical with religious monists, Qutb sought to collapse secular life into religion. His "deepest quarrel was not with America's failure to uphold its principles," Berman explains. "His quarrel was with the principles. He opposed the United States because it was a liberal society" (emphasis added). The most "dangerous element" of that society was, in Qutb's view, the "separation of church and state." His version of liberation entailed an adherence to strict Islamic law ("Shariah") in defense of "freedom of conscience." But such liberation "meant freedom from false doctrines that failed to recognize God, freedom from the modern schizophrenia." It is no great leap to realize the dictatorial implications of this utopian vision, whose enforcement would echo the totalitarian projects of fascism, Nazism, and communism.

Berman wonders who, in the West, will defend liberal ideas against its enemies. Those who admire Ayn Rand know the answer. Rand fought against the mystics of muscle and the mystics of spirit; she fought for a passionate integrated view of human existence that triumphed over the false alternatives of mind and body, reason and emotion, morality and prudence, theory and practice. She fought for reason, but not against spirituality, for productive purpose, but not against creativity, for self-esteem, but not against a humane society of voluntary cooperation and shared values.

But the power of Rand's vision is two-fold: It enunciates broad epistemological and moral principles that guide us in the rational pursuit of rational goals. At the same time, it provides an engine for contextual analysis, which enables us to understand the factors that thwart both moral means and the pursuit of moral ends. Objectivists have been very vocal in stressing the principles of Rand's vision, while often failing to grasp the comprehensive critique that Rand offered of the statist enemies in our midst.

The History of U.S. Foreign Policy: Capitalism Thwarted

Rand, who wrote minimally on foreign policy, recognized nevertheless that "[t]he essence of capitalism's foreign policy is free trade-i.e., the abolition of trade barriers, of protective tariffs, of special privileges-the opening of the world's trade routes to free international exchange and competition among the private citizens of all countries dealing directly with one another" ("The Roots of War").

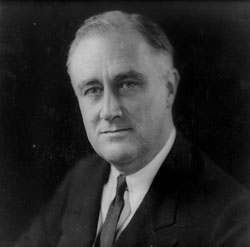

For Rand, capitalism had never existed in its purest form. Still, semi-capitalism was powerful enough to demolish the remnants of feudalism, mercantilism, and absolute monarchy throughout the world. But with the rise of the collectivist, paternalist ideology and nationalistic imperialism of "progressive reformers" such as Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, and Franklin Delano Roosevelt, relatively free markets gave way to government regulation and privilege. The twentieth-century history of U.S. foreign policy, according to Rand, was a history of "suicidal" failure and hypocrisy ("'Extremism,' Or the Art of Smearing"). Failure-because the U.S. had abdicated the moral high ground, destroying economic and civil liberties from within, and losing any rational sense of the country's moral significance. Hypocrisy-because the U.S. often fought evil with evil. Rand maintained that Wilson had led the charge "to make the world safe for democracy," but World War I gave birth to fascism, Nazism, and communism. FDR had led the charge for the "Four Freedoms," but he only empowered the Soviets in the process ("The Roots of War").

Rand had long believed that the Soviet Union was a primitive country, doomed to economic stagnation and systemic collapse. She had once excoriated Ronald Reagan for invoking "fear" of the Soviets, for "exaggerat[ing] the power of the most incompetent nation in the world," which was "not a patriotic service to the United States" ("The Moral Factor"). Her Objectivist Newsletter had featured a series of review essays by various writers who had argued that the parasitic Soviets had stolen military and other technology from the West, and that it was U.S. foreign policy that had stabilized the regime. Drawing from John T. Flynn's book, The Roosevelt Myth, Barbara Branden stressed that FDR was inspired by Bismarck, Mussolini, and Hitler in establishing a liberal corporatist "New Deal" that further devastated a depressed economy (The Objectivist Newsletter, December 1962). Provoking war in the Pacific, Roosevelt used "national defense" as a pretext for resolving the unemployment problem by drafting American boys to fight and die in foreign wars, while sending $11 billion in Lend-Lease assistance to the Soviets, and developing secret post-war agreements with Stalin to surrender nearly three-quarters of a billion people into communist slavery. (Rand herself believed that this strategy made Russia "the only winner" of World War II ["The Shanghai Gesture, Part I"]. She also questioned the wisdom of entering that war's European theater on the side of the Soviets-suggesting that a Nazi-Soviet conflict might have severely weakened the victor [e.g., see "Communism and HUAC" in Journals of Ayn Rand].)

Government intervention in the economy and U.S. intervention abroad mirrored each other in one significant respect: each problem caused by statist intervention led to new interventionist attempts to resolve it. Just as World War I begat World War II, and World War II begat the Cold War, so too did the Cold War beget "hot" wars in Korea and Vietnam, in which more than 100,000 drafted Americans lost their lives. Vietnam especially had laid bare the inner contradictions of U.S. foreign policy. "There is no proper solution for the war in Vietnam," Rand counseled at the time; "it is a war we should never have entered. We are caught in a trap: it is senseless to continue, and it is now impossible to withdraw" ("From My 'Future File'"). Rand had opposed U.S. involvement in both Korea and Vietnam, and wondered why the U.S. had "sacrificed thousands of American lives, and billions of dollars, to protect a primitive people who never had freedom, do not seek it, and, apparently, do not want it" ("The Shanghai Gesture, Part III"). It is advice well worth keeping in mind-anytime the U.S. wages war with the expressed aim to free an oppressed people.

Rand understood that "international politics" among "statist regimes" often entailed a "'balance of power' game"-though she believed that U.S. statist politicians were "crude, naive and innocent compared to their European and Asian counterparts" ("The Shanghai Gesture, Part I"). In contrast to the "range-of-the-moment manipulations" of "Metternichian amorality" on display in the global political arena ("A Last Survey, Part I"), Rand invoked the spirit of the Old Right critics of U.S. involvement in World War II, who had been smeared as "America First'ers" ("Britain's 'National Socialism'"). She despised those who had coined the "anti-concept" of "isolationism" as a means of denouncing "any patriotic opponent of America's self-immolation" ("The Lessons of Vietnam"). Rand was not against all involvement in overseas affairs. In the context of the Cold War, for example, she opposed the appeasement of the Soviets, and recognized the strategic importance of Taiwan and Israel-despite her antipathy toward the latter's socialist, religious, and tribalist nature. Israel was preferable to the Palestinian Liberation Organization, argued Rand, which had abdicated any "rights" it may have once held by engaging in a sustained policy of terror ("The Lessons of Vietnam"; "Global Balkanization" Q&A tape, 1977). Still, Rand stood firmly against the "altruistic" evil of foreign "interventionism" or "internationalism" that had undermined long-term U.S. interests. She repudiated the claim "that isolationism is selfish, immoral, and impractical in a 'shrinking' modern world" ("The Chickens' Homecoming").

The crisis of U.S. foreign policy did not end in Southeast Asia. Containment of insurgencies throughout the world often enraged local populations, as the U.S. propped up puppet dictators to do its global bidding-stationing its troops till this day in over 100 countries worldwide. This policy was partially responsible for the rise of Islamic fundamentalism as an anti-American political force in Iran; the Iranians threw off the U.S.-backed Shah, and elevated Khomeini to a position of leadership. A hostage crisis followed. Supporting the Iraqis in their war with Iran, opposing the Soviets by aiding Afghan "freedom fighters"-the theocratically inclined mujahideen who became Al Qaeda and Taliban warriors-"put the U.S. wholesale into the business of creating terrorists," as Leonard Peikoff observes. "Most of them," says Peikoff, "regarded fighting the Soviets as only the beginning; our turn soon came" ("End States Who Sponsor Terrorism").

A Radical Insight

The crisis of U.S. foreign policy led Rand to a key radical insight-that there was an inextricable connection between government intervention at home and abroad. Rand states unequivocally: "Foreign policy is merely a consequence of domestic policy" ("The Shanghai Gesture, Part III"). When Rand called for a complete "revision of [U.S.] foreign policy, from its basic premises on up," she knew that this would entail a simultaneous repudiation of the welfare state at home and the warfare state abroad, an end to "foreign aid and [to] all forms of international self-immolation." She knew that "a radically different foreign policy" required a radically different domestic one-and that both required a philosophic and cultural revolution ("The Wreckage of the Consensus").

Rand had identified U.S. domestic policy as the "New Fascism." This was-and is-a de facto, predatory fascism, the result of pragmatic expediency and of ad hoc, incremental policies that had enriched some groups at the expense of others. A business-government "partnership" was its "economic essence" ("The New Fascism: Rule By Consensus"). In such a system, she argued, we are all victims and victimizers; the whole society becomes a "class of beggars" ("Books: Poverty is Where the Money Is"). For once the rule of force begins to predominate, the institutional means for legalized predation expand exponentially. "If this is a society's system," writes Rand, "no power on earth can prevent men from ganging up on one another in self-defense-i.e., from forming pressure groups" ["How to Read (and Not to Write)"].

The New Fascism therefore "accelerates the process of juggling debts, switching losses, piling loans on loans, mortgaging the future and the future's future. As things grow worse, the government protects itself not by contracting this process, but by expanding it" beyond its national borders. Just as pressure groups had slurped at the government trough in seeking domestic privileges, so too did they benefit from a whole global system of foreign aid, involving financial manipulation (through, for example, the Federal Reserve System, the Ex-Im Bank, and the IMF), "credits to foreign consumers to enable them to consume" U.S.-produced goods, "unpaid loans to foreign governments, and subsidies to other welfare states," to the United Nations, and to the World Bank ("Egalitarianism and Inflation").

Rand goes further: "If looting collectivists did not exist, America's foreign aid policy would create them." The overwhelming profiteers of this system were those peculiar "products . . . of the mixed economy," those statist businessmen who "seek to grow rich not by means of productive ability, but by means of political pull and of special political privileges." Rand observes "that there are firms here and there, in various businesses and industries, who are growing prosperous by trading with foreign countries, the specific foreign countries who receive American aid. In other words, there are businessmen who are selling their products to the foreign countries receiving American aid and who are paid by American funds-who are paid by the aid money granted to those countries. In other words, some Americans are draining the money, the tax money, of other Americans, into their own pockets, via a longer tour through every corner of the globe which receives our foreign aid. This tax money is taken from some citizens, handed to foreign governments and pressure groups and then comes back to some of our citizens, through those successful pressure groups who have pull in Washington." This was a "siphoning" process, in Rand's view, a "necessary corollary of a mixed economy, or rather the necessary expression of a mixed economy, now being carried to the international scene. It is a civil war gone international; it is pressure groups using foreign countries in order to destroy our own. That is the meaning of our foreign aid policy" ("The Foreign Policy of the Mixed Economy," tape).

Thus, the New Fascism exports "the bloody chaos of tribal warfare" to the rest of the world, creating a whole class of "pull peddlers" among both foreign and domestic lobbyists, who feed on the carcass of the American taxpayer, causing massive global political, social, and economic dislocations ("The Pull Peddlers"). Whereas the Left derided "capitalist imperialism" for this state of affairs, Rand recognized that capitalism, "the unknown ideal," had taken the blame for the sins of its opposite. She lamented the internationalization of the New Fascism; given "the interdependence of the Western world," all countries are "leaning on one another as bad risks, bad consuming parasite borrowers." She recognized how the system's dynamics propelled such internationalization, but advised: "The less ties we have with any other countries, the better off we will be." Suggesting a biological analogy in warning against the spread of neofascism, she quips: "If you have a disease, should you get a more serious form of it, and will that help you?" ("Egalitarianism and Inflation" Q&A tape, 1974). In discussing a section of the 1972 Communiqué between the U.S. and Red China, Rand suggests a universal principle. "[L]ike charity," she writes, "courage, consistency, integrity have to begin at home . . . [w]hat we are now doing to others . . . we began by doing it to ourselves. We are the victims of self-inflicted bacteriological warfare: altruism is the bacteria of amorality. Pragmatism is the bacteria of impotence" ("The Shanghai Gesture," Part III).

This critique of the "New Fascism" is as relevant today as it was in the time that Rand first presented it. Some writers (e.g., Adam Reed, 26 March 2003, SOLO Yahoo Forum) have argued, however, that Rand's critique was limited to-and grounded in-the historically specific period of the Kennedy and Johnson administrations (see, for example, "The Fascist New Frontier," in which Rand cites approvingly the similarly constituted critique of New Leftist Charles A. Reich). But while the world scene has changed immeasurably in the last 40 years, Rand did not quell her attacks on this neofascist system in any of her subsequent analyses of the Nixon, Ford, Carter, or Reagan administrations. Not even the collapse of central planning and the Soviet Union would have given Rand pause in these attacks, because neofascism was never about central planning-even if its current court intellectuals (i.e., the formerly socialist neoconservatives) wish to apply the precepts of such planning to the task of global nation-building. Rand's comments focused not on the historical concretes, but on the principles entailed in interventionism. Like Ludwig von Mises and F. A. Hayek, Rand predicted that the interventionist system would expand its reach, making possible an ever-deepening social fragmentation among warring foreign and domestic pressure groups.

Rand never saw the New Fascism-or what the Left had called "socialism for big business" ("The Moratorium on Brains, Part II")-as authoritarian in character. For Rand, the real "dividing line" between neofascism and dictatorship is "freedom of speech," since "censorship is the tombstone of a free country." This is why she condemned a "servile press" even more than a "censored press"; the "servile press" embraces "'voluntary' self-enslavement," relying on government manipulation of news "'as an instrument of public policy'" ("The Fascist New Frontier"). The New Fascism, therefore, is a kind of liberal corporatism, which keeps in place democratic forms and procedures, while deadening the prospect of real political and social change. Not even an Objectivist sympathizer, such as Alan Greenspan, can stop the system from the boom-and-bust that emanates from the financial levers of the central bank that he controls, or the massive redistribution of wealth that ensues from that control. In Rand's view, even noble actors pursuing noble goals are defeated by this system. The New Fascism can only engender "parasitism, favoritism, corruption and greed for the unearned"; its power to dispense privilege, Rand emphasizes, "cannot be used honestly" ("The Pull Peddlers").

It is a process of privilege-dispensing that, I might add, will only be augmented in the wake of any long-term U.S. occupation of Iraq. Whereas the estimated war costs are over $75 billion, the open-ended price tag on occupation is anyone's guess. Already, officials are suggesting $1 billion in taxpayer start-up costs for the "bidding" process, going directly to U.S. corporations responsible for re-building Iraqi "infrastructure" ("Who Will Put Iraq Back Together?," by Diana B. Henriques, 23 March 2003, NY Times). The projected costs of Iraqi reconstruction are upwards of $100 billion, "the largest postwar rebuilding since the Marshall Plan in Europe after World War II" (Henriques 2003)-a plan that, according to Rand, brought the United States to "the brink of economic ruin" (Letters of Ayn Rand, 490), a typical by-product of the U.S. tendency to "waste her wealth on helping both her allies and her former enemies" ("Philosophy: Who Needs It"). The NY Times reports that the U.S. government has invited "only American corporations to bid on . . . contracts . . . financed by the taxpayer" for reconstruction of transportation, communication, irrigation, medical facilities, education, and utility plants. The bidding process has been a closed one, allegedly because only a select few corporations have security clearance. Of course, these corporations are among the "largest and most politically connected."

It is claimed that the reconstruction will be funded by Iraqi oil revenues for the benefit of the Iraqi people-thus relieving much of the U.S. tax burden. This, of course, remains to be seen-though it is always possible that the Iraqis will not want to invest their money in precisely the way dictated by U.S. occupiers. Not quite a free market. Nevertheless, as one consultant puts it: "Anytime you have an emergency response driven by time, the opportunity for fraud, waste and abuse is huge . . . And when the opportunity is that great, it will occur" (Henriques 2003).

The Objectivist Response

The response of Objectivists to the prospect of this kind of U.S. occupation has been mostly positive (with a few notable exceptions, e.g., Arthur Silber at The Light of Reason). Robert Tracinski, for example, rightfully criticizes the pragmatism and religiosity of the Bush administration, which pays no attention to "context or history" ("The Era of Muddling Through: How We Got Here and Why We're Still Moving," TIA, March 2003). But this does not stop Tracinski from applauding Bush for "a breathtakingly new grand strategy to remake the Middle East," a policy that Tracinski admits "is a kind of indirect colonialism. The colonial administrators will be the nominally independent leaders of Middle Eastern countries-but the essence of their form of government and their foreign policy will be inspired or imposed by the United States of America." Deriding the muddling ways of "Old Europe," Tracinski suggests approval of the U.S. ambition "to remake the world, sweeping aside hostile regimes and securing America's safety" ("New Hollywood and Old Europe," TIA, March 2003).

William Thomas writes ("What Warrants War? The Challenge of Iraq and North Korea") that "[t]he Objectivist view of foreign policy derives from its view of morality. Just as each person should pursue his rational self-interest in his personal matters, so should a proper government uphold the interests of its citizens in its conduct toward other nations." Thomas goes on to say that it is a "basic tenet" of "Objectivist political philosophy . . . that the only just governments are the free countries-and all the free countries are natural allies. Free countries are those that essentially embrace the principles of liberty, including freedoms of speech and assembly, competitive elections, the rule of law, and property rights." In Thomas's well-reasoned discussion of principles, the New Fascism is never mentioned. And though he admits that certain foreign policy goals require us "to hold our noses" when entering into "alliance[s] of convenience" with less free countries, he does not seem to appreciate the extent to which such pragmatic considerations have brought the globe to the current crisis.

In the end, however, Thomas supported the war in Iraq-and a possible war with North Korea as well. He sees the post-war reconstruction as a requirement, "the only means of eliminating the longer-term threat." Keeping the peace, funding our allies, and building a free Iraq, will require "billions upon billions of dollars . . . for reconstruction and re-education." Reconstruction? Re-education? Funding our allies? I am tempted to ask the perennial Randian question: At whose expense?

To his credit, Thomas recognizes that "if it is culturally or financially infeasible to transform . . . enemies into allies-or at least into stable, non-threatening regimes, then war will not resolve the longer-term threat . . ." To his credit, Thomas accepts the possibility that U.S. occupation might "fuel anti-Americanism throughout the region." To his credit, Thomas understands "that political policy is a symptom, but culture is the root cause." Still, he supports the risk of war and a long-term occupation that empowers "better educated" and "more secular" Iraqis, so as to "cement the transformation" of other Middle Eastern nations.

Pisaturo's Epistle

To "cement the transformation" is Ron Pisaturo's goal as well. Except that he offers a much more robust strategy. Writing in the aftermath of the World Trade Center disaster, Pisaturo is an unabashed Objectivist advocate of a new U.S. colonialism ("Why and How to Conquer the Savages," Capitalism Magazine ).

Pisaturo begins on the correct premise-that Americans have the right to defend themselves from murderous attacks. But he goes further: He urges the creation of a new Middle East as if from a state of nature; his regional tabula rasa, however, requires the "nuclear" incineration of millions of "savages" in order to start from scratch. Pisaturo stands, like Archimedes, outside the context he wishes to reconstruct. His canvas-cleaning strategy is the logically horrific conclusion and destructive essence of his utopianism. It applies literally to 'no-where' on earth-though, in all fairness, the Brave No-World of Ron Pisaturo is far more dystopian than it is utopian.

According to Pisaturo, the U.S. must crush all the "evil governments" of the Middle East (e.g., Iran, Iraq, Syria, Libya, Sudan, Afghanistan, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and other "murderous regimes"). This is a sentiment shared by his Ayn Rand Institute colleagues, including Yaron Brook (ARI Media, 10 April 2003) and Leonard Peikoff ("America versus Americans," Ford Hall Forum, 7 April 2003)-both of whom see Iran as the next target in the war against Islamic fundamentalism. Pisaturo argues that the U.S. government must take back the oil fields for Western oil companies, appropriate Arab assets worldwide (including "real estate, bank accounts, and all other financial holdings"), and "isolate, colonize, and settle the lands the savages now roam." Sensing perhaps that such a proposal for massive colonization of the region might entail an exponential increase in U.S. tax rates and in the size of the U.S. military-perhaps even necessitating conscription-Pisaturo declares that if the Western oil companies "agree to pay the cost of waging this war," then the U.S. government could continue "occupying and defending these oil-rich territories." Once the U.S. has seized the Middle East-I suppose after several years of waiting for the nuclear fallout to settle-it will allow American pioneers to enter the region as international homesteaders. "Over time, pioneers, with the paid support of our military, can go into these isolated territories, subdue the remaining savages, install a civilized, colonial government protecting the rights of both the pioneers and the savages, and settle the land-as American pioneers subdued the savage, murderous American Indian tribes and settled America." Of course, the "savages" will eventually realize that they will be the "most fortunate beneficiaries" of such colonialism.

In truth, Pisaturo's view of the Arab world finds inspiration in Rand's own condemnation of Arab terrorists as "savages" (on "The Phil Donahue Show"). She saw the "Arab whose teeth are green with decay in his mouth" ("The Left: Old and New") as living "a nomadic, anti-industrial form of existence" ("Requiem for Man"). But this is a far cry from Pisaturo's genocidal call for an American Lebensraum.

I submit that this "cure" is far worse than the disease.

Let's analyze Pisaturo's proposal more closely. The Western oil companies whose interests Pisaturo wishes to defend are the same Western oil companies that collaborated with the U.S. government and Middle Eastern governments to develop the oil fields. The U.S. government socialized much of their risk, and replaced the colonizing British as the chief power in the region. From the 1920s through World War II and beyond, the government and the oil industry worked hand-in-hand to win concessions from, and bolster the power of, various "pro-Western" Arab regimes, such as Iran, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Jordan, trying to create stability with money, munitions, and political machinations (see Sheldon Richman's "'Ancient History': U.S. Conduct in the Middle East Since World War II and the Folly of Intervention"). The "pull-peddling" between the oil industry and the various governments was a quintessential expression of the New Fascism. (Rand did not examine these oil industry-government ties; but she did believe, ironically, that U.S. foreign policy had "brought the entire Western world to the position of a colony ruled by Arab sheiks" ["The Energy Crisis, Part II"]).

When a neoconservative defends the ideal of a new U.S. colonialism, I am disgusted-but not surprised. Neoconservatism was founded-as a movement-by a group of disaffected socialists and "social democrats." Its modern representatives are now the intellectual architects of U.S. foreign policy. Having given up the fiasco of defending economic central planning, they now embrace global social engineering to bring the ideal of "democracy" to the rest of the world. And if some of them get their wish-of establishing a new "American Empire"-they'll find out that the pretense of knowledge, which destroyed socialism, will similarly destroy their Wilsonian designs. We simply never know enough to construct or reconstruct, wholesale, social systems and nations from the ground up. (On this point, see especially Hayek's Law, Legislation, and Liberty, Vol. 3, pp. 107–109.) Such schemes for a Pax Americana are fraught with endless possibilities for negative unintended consequences, however "noble" the intentions.

So "nation-building" as a neoconservative goal is understandable-given the socialist lineage of its champions. But when an Objectivist advocates mass murder and U.S. colonialism and supports the oil industry's employment of the government like a mercenary private protection agency to secure its foreign financial and material holdings, it is beyond baffling. These are the same kinds of Objectivists who would accuse the U.S. Libertarian Party of "context-dropping" (in contradistinction to "atomic-bomb-dropping") for wanting to build political solutions on a fragile philosophic and cultural foundation. Pot. Kettle. Black.

Rand's Tri-Level Model

Human liberation from tyranny is a noble and just cause. But the pursuit of freedom, like the pursuit of justice, can never be disconnected from the context that gives it meaning. And ethical discussions cannot be considered in a vacuum, disconnected from other levels of analysis that help us to understand the nature of that broader context.

For example, in a recent essay, Objectivist Joseph Rowlands begins an analysis of the principles upon which a rational foreign policy must be built. Based on an individualist ethics, such a policy must recognize that there are no fundamental conflicts of interest among rational men-or rational nations. Echoing Rand, Rowlands states that any nation has the right-though not the obligation-to retaliate against those nations that initiate force. Justice requires judgment and consistency or "evil wins by default." These are important insights-but their application requires careful attention to context. A "nation" does not exist separate from the individuals who compose it. To equate a "nation" with that nation's "government" and to assume that the government can and should come to the aid of other nations under attack may be a valid application of an individualist ethics-only if the assisting government generates its revenues and armed services through voluntary means. The principle cannot possibly apply unconditionally to less-than-ideal social systems.

Indeed, Rand's view that the rational interests of human beings do not conflict pertains to laissez-faire capitalism. "In a non-free society"-such as the one we have today-"no pursuit of any interests is possible to anyone; nothing is possible but gradual and general destruction" ("The 'Conflicts' of Men's Interests"). In examining the "interrelated considerations which are involved" in judging one's rational interests, Rand stresses first and foremost reality and context. And one cannot drop the reality of the given context when offering ethical advice in the realm of international politics. We can certainly strive toward an international political order that recognizes the individualist principles Rowlands emphasizes, but those principles will never be achieved globally in the absence of a similar domestic movement. Rand's maxim is worth repeating because it is right: "Foreign policy is merely a consequence of domestic policy." If governments rob the wealth of their own citizens to fund foreign adventures, and if they conscript people to fight and die in such adventures-all ethical bets are off.

In Ayn Rand: The Russian Radical, I explored Rand's mode for analyzing every social problem on three distinct levels: (1) The Personal, in which she focused on the psycho-epistemological and ethical dimensions; (2) The Cultural, in which she focused on the linguistic, pedagogical, aesthetic, and ideological dimensions; and (3) The Structural, in which she focused on the political and economic dimensions. Every social problem-and solution-entailed mutually reinforcing personal, cultural, and structural factors. This is why Rand maintained: "Intellectual freedom cannot exist without political freedom; political freedom cannot exist without economic freedom; a free mind and a free market are corollaries" ("For the New Intellectual"). It is also why she criticized Libertarians: for seeking political and economic change without the requisite personal and cultural foundations. But it is just as faulty to focus on ethics or culture to the exclusion of structural realities. By disconnecting any level from the others, we drain the radical life-blood out of Objectivism and ossify Rand's system into a form of conservatism. The active embrace of one-dimensional thinking by some Objectivists undermines fundamentally Rand's contextual, dialectical way of looking at the world. It is a perverse kind of "vulgar" one-sidedness that has led "far too many Objectivists [to] act as if they are conservatives who simply don't go to church," as economist Larry Sechrest suggests (OWL list, 29 January 2003).

An Objectivist resolution to the current global crisis will require a veritable revolution on every level. Rand stresses the interconnectedness between levels: Rampant tribalism is "a reciprocally reinforcing cause and result" of "rule by brute force" ("The Missing Link"), she argues, just as the neofascist "mixed economy" is "the political cause of tribalism's rebirth" ("Global Balkanization"). Tribalism and statism require each other; this is as valid an assessment of the situation in the Middle East as it is of the situation in the United States of America-whether we call the interventionists "theocrats" or "social democrats."

This is not to say that the U.S. government is the moral equivalent of the despotic regimes in the Middle East. Context-keeping means, among other things, keeping a sense of proportion. One of the most important insights on this subject comes from Lindsay Perigo, who writes of the libertarian antiwar crowd: "They invoke imperfection to justify inaction against evil. They say America may not liberate slave pens because America itself is not wholly free & is becoming less free. They blur the distinction between 'not wholly free' and 'wholly unfree' & effectively advocate surrender of the former to the latter. They evade the fact that in America, one is still free to proselytise against its slide into statism, just as they are free to apologise for despots." While I take exception to Perigo's belief that the antiwar crowd-which is far from monolithic-has offered nothing but an apologia for despots, I do believe that he puts his finger on a crucial principle and problem: Just because we cannot do everything to change the system radically and immediately, does not mean that we should do nothing to lessen threats to our freedom. On this point, Perigo and I are in complete agreement.

The bottom line, therefore, is indeed practical: Will a U.S. occupation of the Middle East lessen despotism-or provide renewed impetus for its long-term growth at home and abroad? Is there not any other way to deal with such despotism short of establishing a new U.S. colonialism? That I have argued for surgical strikes to neutralize outright and imminent threats to American security coupled with a long-term shift toward strategic disengagement suggests one alternative.

Such practical alternatives cannot be considered, however, without addressing briefly the issue of "Weapons of Mass Destruction" (WMD). It is said that the existence of WMD changes the whole equation significantly. Looking at what terrorists can accomplish with box cutters and commercial passenger jets, the destructive possibilities are infinite should they ever come to possess WMD. Much of the practical argument for intervention in Iraq, for example, revolved around the belief that any illegitimate chemical, biological, or radiological weapons that it possessed could be dispersed to terrorist organizations, like Al Qaeda. In my view, however, the pro-war advocates did not present any conclusive evidence of a link between the lethally opposed Ba'ath and Al Qaeda gangs. That it was "pragmatic" U.S. foreign policy that first gave Hussein's regime the wherewithal for the production of some of these weapons, that the U.S. could have used its own overwhelming WMD stockpile effectively to contain Iraq by threat of "mutually assured destruction," that a growth in direct U.S. intervention could make WMD proliferation among potential terrorists more likely, since it becomes their prime manner of counteracting an overwhelming U.S. military force-have all been dismissed by pro-war advocates.

In the end, however, it is simply wrong to think that an advance in the technology of death changes the central principle involved in our understanding of the roots of war. As Rand puts it, "there is something obscene in the attitude of those who regard horror as a matter of numbers." Indeed, "it makes no difference to a man whether he is killed by a nuclear bomb or a dynamite bomb or an old-fashioned club. Nor does the number of other victims or the scale of the destruction make any difference to him . . . If nuclear weapons are a dreadful threat and mankind cannot afford war any longer, then mankind cannot afford statism any longer . . . if war is ever to be outlawed, it is the use of force that has to be outlawed" ("The Roots of War").

A military battle of any scope is like a "political battle"-"merely a skirmish fought with muskets"; for Rand, "a philosophical battle is a nuclear war"-and only rational ideas will ultimately win it ("'What Can One Do?'").

Conclusion

The Middle East is a region with many oppressive, theocratic regimes at war with human life, human liberty, and human justice. But even when the U.S. government retaliates appropriately against those who act out their jihad-ic desires, it cannot hope to transform that region's despotism by creating, necessarily, a garrison state at home to support a colonial occupation abroad. Destroying American liberties in order to "liberate" the few remaining "savages" who survive the nuclear winter is not a prescription for peace, "homeland security," or freedom. Unless one wants the New Fascism to look a lot like the old one.

Those who think that the interventionist power of the state will wither away, after it has built a mighty colonial fortress, atop deficits and debt, rising taxes and the threat of conscription, are suffering from a Marxist delusion. Objectivists are neither Marxists nor conservatives.

Objectivists are radicals. And it is only by reclaiming Rand's radical legacy that we can begin to understand this global crisis as a means to overturn the irrationality and statism that breed it.

Comments here (Rebirth of Reason site)