This article appeared in Folks (18 January 2018)

The Folks Interview: How

the Queen of Selfishness Taught Me to Accept My Disability

By

Robert LeRose (Folks magazine)

Whether it’s his chronologically arranged correspondence, his indexed research notebooks or his extensive alphabetized vinyl record and CD collection, one of the first things you discover about Chris Sciabarra is how well organized he is.

Some might find this predilection for organization extreme, but it has given Chris a measure of control over his life that is missing from his physical health.

Chris Sciabarra discovered Ayn Rand as a teenager, struggling with a rare gastrointestinal disorder.

Chris was born with Superior Mesenteric Artery Syndrome (SMAS), a rare and sometimes fatal gastrointestinal disorder in which part of the duodenum is squeezed between the abdominal aorta and an artery. Throughout his childhood, he suffered intense abdominal pain, nausea and excruciating bouts of diarrhea. He endured over 60 surgical procedures, with varying degrees of success.

After one bypass surgery, he “was beginning to manifest symptoms consistent with a ‘dumping syndrome’—that is, the blind-loop that had been created by the bypass was causing severe malabsorption and I simply had increasingly awful incidences of urgency that eventually made it impossible to travel for any length of time without needing to get to a restroom.”

Except for short excursions, that urge to move his bowels constantly and his need for 24/7 access to a bathroom (he calls it the Oval Office) keep him close to home to this day.

SMAS might have hindered his mobility, but not his mentality or curiosity. Chris earned a Ph.D., publishes a wide range of articles, essays, and books, blogs incessantly, and became a scholar of Ayn Rand—the founder of Objectivism and a fierce critic of altruism. Given that Chris’s well-being has involved relying on devoted family and friends, it is surprising that he credits Rand with helping him come to terms with the limits of his condition and giving him the tools to thrive.

We caught up with the 58-year-old Brooklyn, New York-based author to explore this contradiction and why “there isn’t a day that passes where I don’t count my blessings.”

When and how did you first discover Ayn Rand?

I was first exposed to the work of Ayn Rand as a senior at Brooklyn’s John Dewey High School. I was always free-market oriented in my politics, and routinely debated my classmates in an advanced placement course in American history. My sister-in-law told me she was reading a novel called Atlas Shrugged, and said that a lot of what I was saying sounded like its author. Not being a regular reader of fiction, I ended up picking up Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal, a somewhat thinner book. Unlike most readers who come to Rand through her fiction, I actually read all of Rand’s nonfiction before picking up a single work of her fiction.

Obviously she had a profound influence on your life. Describe it.

The immediate impact was intellectual; her books introduced me to a whole new literature in politics, economics, and social theory, which gave me the tools by which to more deeply comprehend the moral and practical arguments in favor of free markets.

But she also helped you deal with your health issues?

Not only her work, but the work of her protégé, the late psychologist Nathaniel Branden, who became a personal friend of mine. He was known by many as the “father of the self-esteem movement.”

What did you take away from them?

Growing up, I had learned various “survival techniques” to deal with severe health problems; writing in a daily diary from age 11 was one way of articulating my thoughts and feelings. Therapeutically, it helped me not to wallow in self-pity. I learned the importance of seeing myself as a bundle of abilities and possibilities, in spite of a disability. In later years, their work helped me to understand the genuine importance that self-esteem plays in valuing our self-worth and our ability to rise above obstacles. It certainly gave intellectual weight to the old adage that with every closed door, a window opens—even if you have to kick it out to breathe freely.

Therapeutically, [Ayn Rand] helped me not to wallow in self-pity. I learned the importance of seeing myself as a bundle of abilities and possibilities, in spite of a disability.

Many people assume that Objectivism and compassion towards the disabled and chronically ill are incompatible, yet you still find much value in Rand. How do you reconcile that?

I consider myself somebody who has been influenced by Rand, but certainly not an “orthodox Objectivist.” It is simplistic to dismiss Rand’s views by caricaturing them as “me-first” and to hell with everyone else. While Rand did not believe that we had a moral duty to help those who were disabled, she had nothing against private, voluntary charity—giving of oneself to help others or to those whom we care about. For her, charitable giving can only be socially benevolent when it is a voluntary extension of one’s values.

What did you learn from Rand that strengthened you?

It is ironic that the “goddess of selfishness” gave me inspiration as a teenager, suffering from chronic illness: I took away from her work the idea that it was possible to survive and flourish by virtue of the passion of productive work and pride in one’s achievements. That passion and pride has been an enormous source of inspiration, given how much I’ve published in my lifetime.

It is ironic that the “goddess of selfishness” gave me inspiration as a teenager, suffering from chronic illness.

Your condition forces you to spend a lot of time in the bathroom and lead a restricted life. What buoys your spirits?

My writing, blogging, and editing of The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies and of other projects is certainly my passion—and that, in itself, has enormous therapeutic value as well. It keeps me “centered,” so that even though my illness creates enormous obstacles to my ability to travel or to work uninterrupted, I’m often preoccupied by the goals I seek to achieve. I also enjoy taking time to keep my “background” alive, even while I’m doing work—whether it’s the television playing a favorite film or listening to great music. I’ve also had pets that have been constant companions through all the ups and downs. There is something wonderful about having a pet that only “pet people” understand; it is the kind of connection that is so life-affirming, so full of fun. Until it isn’t—and then, it provides a palpable lesson of caregiving for those of us who require so much caregiving ourselves.

What are some challenges in your life, especially any that may not be so obvious?

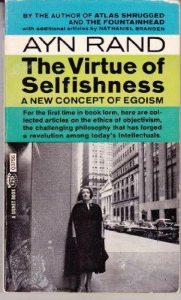

The cover of one of Ayn Rand’s nonfiction books, ‘The Virtue of Selfishness’

The biggest challenge is travel and long phone conversations—and Lord knows, I could talk your ear off! But there are some things that so many of us take for granted that I have to often belabor—like, can I take a walk to a store, and make it back in time, in case I get sick? When you are in a constant state of discomfort and urgency, it’s difficult to gauge. It has made me very good at riding a bike strategically to and from a store, which cuts the travel time dramatically, and puts a lot less strain on my innards.

Dealing with a chronic condition can take an emotional toll on anyone. How do you cope with yours?

I don’t think I’m constitutionally capable of keeping anything in. So that means learning to be as open as I can be with others, and with myself; and if that requires a good cry—well, damn it, I’ve earned it. And if I find myself pissed off at somebody, I let ’em have it. Tactfully, of course.

But I’m not going to sugar-coat this; I do think that the cumulative effects of illness and of life’s twists and turns have had an impact on my coping skills as I’ve aged. If it requires a little extra time to rest, to reflect, or to cry, I let nature take its course.

I can’t think of anything more life-affirming than love.

Aside from work, music and film, what makes life most worth living for you?

Love. I have an almost boundless capacity to be loved and to give love in return. And I mean love in all its facets: the love of family, of friends and colleagues, and of those special people that come into our lives now and then, with whom one can share the kind of love that is spiritually and physically intimate. I can’t think of anything more life-affirming than love.

What surprises most people about your condition?

I don’t typically look sick. I can walk, I can talk myself into oblivion, I laugh. It’s not that you can see my condition, like I’m missing a limb or walking with crutches. It also leads some folks into a false sense that there’s really nothing wrong inside of me. That, unfortunately, can be frustrating, because it is extremely difficult to keep explaining to such people what limitations I have and why I have them.

Chris Sciabarra: “We learn by trial and error, sometimes painfully, what we can do, how far we can challenge ourselves, and what might be just a hair’s length away from our grasp.”

Despite a lifetime of discomfort, you come across as resilient and even well-adjusted. What’s your secret?

One thing I learned from Branden’s work is that one must practice the art of owning one’s emotions. There is a price to be paid by “the disowned self,” as the title of one of his books suggests. Especially for a person who has had a lifelong illness, it is important to accept what is as the basis for all that could be. It’s easy to say “Don’t be afraid to fail” or “Don’t let this illness make you feel vulnerable or at the mercy of forces beyond your control.” But how can we possibly learn about our limitations if we don’t test ourselves?

How can we possibly learn about our limitations if we don’t test ourselves?

And the answer?

We learn by trial and error, sometimes painfully, what we can do, how far we can challenge ourselves, and what might be just a hair’s length away from our grasp. As you come to realize and accept the parameters within which you live your life, there is nothing to stop you from living your life to the hilt.

|

|